American Eve (46 page)

Authors: Paula Uruburu

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Historical, #Women

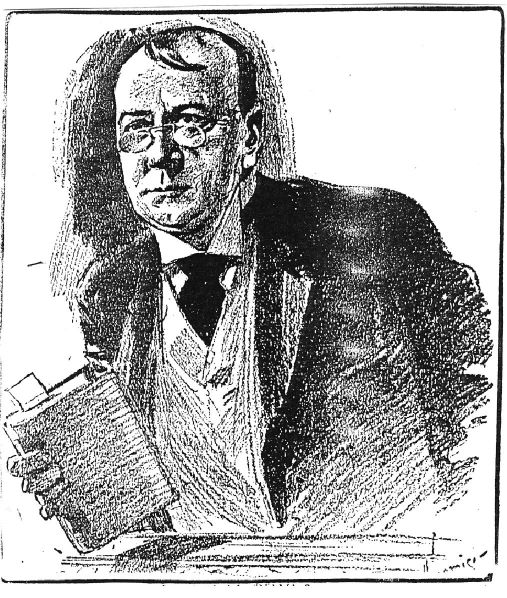

Thaw’s head counsel, Delphin Delmas.

country, much to the vexation of President Roosevelt, who tried to suppress (unsuccessfully) the printing of the transcripts on both moral and practical grounds; he feared that reading accounts of the sordid and depraved subject matter of the case would cause further moral ruination of the citizenry, and that Americans were so preoccupied with the Thaw trial they were ignoring their own work. So it was from the newspapers (and not her in-laws) that Evelyn first learned just who Harry’s new head counsel would be—a short-statured, eloquent, and shrewd barrister who the papers said deliberately accentuated his resemblance to Napoleon, with both his hairstyle and his characteristic pose of putting one hand inside his vest. More important, in his illustrious West Coast career, Delphin Delmas had never lost a case, including one in the not-so-distant past in which he had earned an acquittal for a murdering client on the basis of the unwritten law—the quaint Victorian notion that a man can snuff out another man’s life to avenge a wife or sister with impunity. Even so, thought Evelyn, he could very well be meeting his Waterloo with Harry K. Thaw.

After so much legal wrangling over courtroom strategy and mumbo-jumbo habeas corpusing and maneuvering, the day finally came when Evelyn was delivered by car to Mother Thaw’s hotel early in the morning. She was greeted at the door by Delphin Delmas. With only a minimum of polite preliminaries, he sat her down in the parlor of her mother-in-law’s suite. Evelyn could read nothing in his inscrutably imperial look but sensed that something was terribly wrong as he began to speak in a somber silken voice. She fixed her gaze on the distinctive oiled forelock on Delmas’s large head as he leaned toward her, meeting her eye-to-eye. And then he told her of “their” plan.

When she understood what he was asking her to do, Evelyn was dumbfounded. It was quite simple, really, Delmas told her. All she had to do was tell the story of her relationship with Stanford White—the whole story, in living, lurid detail. A wave of nausea passed through her and her hands began to tremble. Mother Thaw, completely motionless, sat wedged like an overfed crow on a tufted divan against the far wall. She said nothing.

“But,” Evelyn almost whispered, “it is an unthinkable thing that I must stand up in open court and tell . . .” She trailed off.

There was no other way, Delmas told her.

“Nothing less will serve. Your husband’s life is in the balance.” Then he added, “After all, what does it matter?” Evelyn shivered as a second wave of nausea gripped her near the throat.

“What does it matter? What does it matter?” The phrase reverberated in her brain. To get up in front of a judge, lawyers, a jury, the press, the world—and tell the story of her debasement? Tell all those secrets that she had kept for so long and had been exhorted by Stanny to keep hidden forever?

With the very unfortunate exception of Harry, Evelyn had kept her promise to White for six years and never told anyone. In fact, until he declared to nearly a thousand witnesses that White had ruined his wife, with the exception of his mother, Harry had kept the secret as well. What would everyone think of her? A thousand things tracked sharply through her brain, not the least of which was what Stanny had said over and over about girls who tell such things: “They come to a bad end.” Then there was her mother’s reaction to consider. And her brother’s. Feeling as if she had suddenly seen the Medusa, a blurry-eyed Evelyn barely glanced over to the black silent form on the sofa. Once the tremors subsided, Evelyn also sat completely still and stared out the window. Delmas waited for a response, his hand in his vest pocket.

“What does it matter?”

She looked over Delmas’s shoulder without seeing anything distinctly, unconsciously shut-off, just as she had the morning after her undoing by Stanny. The phrase haunted. As she wrote in 1915 of her train of thought on the days following this meeting, “I tell myself this a hundred times a day. Other women have gone into Court and told stories, without so much as turning a hair, which were infinitely more discreditable to themselves. ” But she knew that wasn’t true.

Seeing no other viable defense, a resigned and frightened Evelyn was under no delusion about the nature of what she was expected to do. Or what she would have to endure as a result. Moreover, she realized fully for the first time that for better or infinitely worse, her entire life and identity were inextricably and everlastingly bound up in Harry’s psychotic act.

SACRIFICIAL LAMB CHOP

In the handful of days before her testimony was scheduled to take place, Evelyn became obsessed with the awesome, faceless power of the public’s “insatiable curiosity.” During certain of the darkest moments before her testimony, Evelyn considered that: “Any well-kept secret takes on a new horror” and leaves one feeling “stripped and naked and defenseless—and open for an awful beating.” As for the Thaws, Evelyn knew that none of them ever doubted that she would hesitate to bare her shredded soul for Harry: “They took it for granted that I should be pleased to have the opportunity to save him from the electric chair. After all, in their private opinion, I was already a fallen woman who could fall no further . . . they expressed their hope that Harry would be shown through [my] testimony in the light of a saint, and that is enough.”

During one early meeting with Harry’s defense team, Evelyn weakly hinted that the evidence might reveal Harry to be something other than what they were making him over to be, but she was “sshhed out of the room” by the Thaws, who had spent such a long time covering up for Harry that it was an automatic response.

Evelyn soon came to comprehend fully not only the terrible fix she was in but that the fix was in. In weighing all the facts and her options, Evelyn saw that there was little room for choice in the matter. In spite of what he had done, she didn’t want to see Harry electrocuted. She flashed on the hideous, shuddering image of the pitiful elephant Topsy, whose electrocution on the Coney Island boardwalk had been captured by Edison for the nickelodeons a few years earlier. And she needed no further evidence that Harry was indeed crazy, but an insanity plea seemed out of the question as far as he and his clan were concerned. She also knew enough about the law and a wife’s lack of rights in marriage and property matters (in those days before pre-nuptial agreements) to see that as Harry’s widow she would get as little as possible from the miserly Thaws. Perhaps even nothing. Their formidable battery of high-priced lawyers would see to that, and she had no money of her own to mount any kind of defense. And if Harry was found insane and sentenced to an asylum, at best she might have to live indefinitely with the Thaws in dismal repentant dependence on them until such time as Harry was released. Knowing Harry as she did, she knew that day might never come. Her best and only hope was that he be acquitted.

Although she wrote years later with nostalgic bravado that she was “determined to tell all that [would] help him,” at the time Evelyn also considered “a very patent alternative.” She questioned whether any human being, no matter how momentous the issue, should be made to undergo the humiliation she would surely suffer on the witness stand. Considering all Harry had said and done in the name of her so-called honor and American girlhood prior to the murder, Evelyn wondered why the issue of preserving her honor no longer applied. Of course, she knew the answer, but still she contemplated the heroic actions she had read in books of “prisoners who have risked death rather than the honor of their wives should be questioned.” But Harry’s heroism was “not of that variety, ” nor was he the kind to be satisfied with “posthumous honors.” If his lawyers wanted to preserve the image that he was sane, Harry would have to be kept as far away as possible from the witness stand, while Evelyn would have to be, as one Broadway denizen wrote, “grilled like a sacrificial lamb chop.”

As the day of her testifying neared, Evelyn appeared to those around her like someone in a trance, acting just as she had the night of the murder. Some started to speculate that the ethereal Evelyn Thaw was on the verge of a nervous breakdown. It would also become clear enough to even casual observers that Evelyn’s only other acquaintances, theater people and Bohemian types, were powerless, not very reliable, and not likely to come to her defense—described in the

World

as “nauseous representatives of the common types of the Tenderloin—waiters, chorus girls, bell boys, cab drivers, private detectives, chauffeurs, doorkeepers, theatre hands, models, valets and other habitués of that part of the city.” In this Evelyn shared the fate of White, whose highbrow friends at the other end of the social scale suddenly became merely clients who found it convenient to remove themselves from the city for the duration of the Thaw debacle, “high-tailing their high-toned arses to Europe or South America while the Thaw circus was in town.”

The fact that Harry Thaw continued to speak confidently about Evelyn, considering all he had done to her (and countless others), reveals Harry’s mad capacity for self-delusion. Of course, the same could be said about his family and attorneys as well, even if they believed Evelyn would be able to come through successfully in the face of William Travers Jerome’s ferocious tenacity, withering prosecutorial style, and years of experience. He had reduced older, much more experienced men to real tears, so what chance did little Evelyn stand? Surely no amount of coaching or prompting or prior performing as a utility girl in the chorus could prepare her for Jerome’s inevitable onslaught. And it was all to be conducted in front of the watchful eyes of hundreds in the courtroom—and by extension the rest of the nation and the world beyond.

Throughout all the preliminary discussions about her testimony during visits to Harry in the Tombs, Harry seemed to Evelyn increasingly, ridiculously pleased with himself. In her account in 1915, Evelyn spoke of Harry’s enthusiasm, of how he looked forward to her appearance in the witness box, “where she was to introduce him as if he were one of the knights of the Round Table.” Although he remained obstinately silent in the face of alienists and medical doctors who he said, “haunted him while in the Tombs,” Harry was absolutely and girlishly chatty when reporters visited. Speaking to a

Times

reporter one day while Evelyn was there, Harry said proudly, “Wait till my little wife gets on the stand and you’ll hear a story such as you have never heard before.”

Evelyn’s reaction was slightly understated: “I [did] not share Harry’s enthusiasm.”

THURSDAY, FEBRUARY 7, "HUMAN SACRIFICE ON THE ALTAR OF LOVE ”

Prior to her appearance on the stand, the general professional opinion around town was that Evelyn’s talents as an actress were unremarkable. As a result, at first there was a great deal of speculation that she would be coached and that her answers would have to be “rehearsed” by Harry’s defense team. But not even this could make her ready for every possible issue or question that would be raised (as Delmas told her without much emotion). Evelyn fretted in her chair at the hotel, her head pounding and her eyes burning with the force. She asked Delmas one more time what she could expect.

He looked at her solemnly: “My dear child,” he said, “I cannot tell you, no one can tell you what questions Mr. Jerome will ask you. He himself does not know as yet. You must do the best you can, and I will protect you to the best of my ability. That is all.”

On Thursday, February 7, the moment Evelyn dreaded and an entire nation had been waiting for arrived. As she described her feelings, “I went into Court that morning with all the sensations of one already condemned. . . .” Outside the building and in the corridors, a crush of people tried every possible means to force their way into the courtroom, past both the animate and inanimate barricades. In the days before Evelyn’s testimony, the security had been somewhat lax, but on the day she was to be the star witness, bars had to be installed to keep the curious crowd of thousands from streaming inside. Mounted police strained to push back near hysterical women who kept surging forward to get a glimpse of the “lethal beauty.” “Half a score” of the most aggressive females actually succeeded in getting seats in the back of the noisy courtroom, as befuddled policemen were unprepared to physically restrain ladies, many dressed in their “gayest Sunday best.”

And then over the commotion a court official shouted: “Evelyn Nesbit Thaw!”

As if everyone in the packed courtroom had been struck dumb simultaneously, a miraculous palpable silence fell. The only exception was the sinister “rustling of paper from the Press tables.” Evelyn emerged from the judge’s chambers, walked slowly and gracefully toward the witness stand, and took her seat. A court attendant handed her a Bible, which she held while being sworn (“which is a rather impressive business”).

“You do solemnly swear to tell the truth,” he said earnestly.

She bowed her head mechanically and sat down as the scrape of the chair leg echoed through the large room. Even Harry sat quartzlike and uncharacteristically immobile.