American Eve (49 page)

Authors: Paula Uruburu

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Historical, #Women

“Did you understand that Thaw was paying honorable courtship to you?” he asked. In reply Evelyn asked, “What do you mean by courtship? ” To her surprise and everyone’s amusement, Jerome floundered. It was one of the few smiles that she showed during the proceedings.

He then asked her whether she traveled under an assumed name in Europe. Evelyn said, “No.” She began to see that Jerome was making his case as he went along, “searching haphazard and for information he did not possess.” A series of questions followed about the hotels they went to, about who paid the bills, about her feelings for Harry, about whether or not she knew at the time that her mother had begun a suit against Thaw for kidnapping her. As Evelyn recalled, “The questions were beginning to tire the Court; there was a stirring and a shuffling of feet.” Then Jerome came back at her with “a more brutally direct question.”

“Did you ever receive money from White after you reconciled with Thaw?”

“Never in any way, shape or manner,” was her reply.

It wasn’t true.

A RECORD "KEPT CLEAN FOR EVIL MEN ” BUT NOT FOR HER

Harry’s one quarrel with Delmas throughout Evelyn’s days of testimony was that during his examination of her, Delmas was unable to get the names of the others involved in White’s atrocious crimes mentioned for the record and for all to hear. He wanted no more of this whispering into Jerome’s ear or expurgating testimony to protect men who were “ages away from being innocent.” But Jerome had seen to it that all those not directly involved in the murder were protected, so reporters were forced to print blanks in their stories where names ordinarily would be. As Evelyn saw it, “The record was kept clean for evil men but not for me.”

By March 1907, postcards of Evelyn were selling rapidly; the demand reached half a million in a single month. According to one printer, his presses were going “night and day. And night.” Evelyn’s testimony finally ended, but the Thaw case steamrolled on.

The trial that had begun on January 23, 1907, found itself thrust into April. On April 11, the jury began its deliberations. Thousands milled around outside the courtroom and the prison awaiting the verdict. The sequestered jurors were locked in debate. They were out forty-seven hours and eight minutes. During that time, the crowd waited and speculated and shivered in the cold rain. Some created a makeshift tent city on the streets outside the Tombs and the courthouse. The police did everything they could to clear them out, but the effort was futile. It was like herding cats.

Finally it was announced that a verdict had been reached.

The serious-looking group of twelve, dressed in their sober suits, reentered the courtroom. All eyes were riveted to the foreman as he stood to read the verdict.

Seven votes for guilty and five for not guilty by reason of insanity.

It was a hung jury.

The packed courtroom erupted in cries and shouts. Reporters rushed out the door in one tumultuous wave. At first, Harry buried his head in his hands. He then began to rant and swear. He pounded his fists on the table as several lawyers tried to restrain him and then those left in the room watched as he broke into hot tears, realizing that he would be back in a cell and would not be going home the avenging angel. As a palsied Harry was taken out of the courtroom, back to his cell, past the clutching black-gloved hands of his distraught mother and sisters, a wordless, emotionless Evelyn sat perfectly still in her seat. Only the trembling of her bottom lip indicated that she had heard the verdict. The sphinx once again. The late-edition papers announced to an astounded public that there would have to be another trial. And “the desperate game of life and death would have to be replayed.”

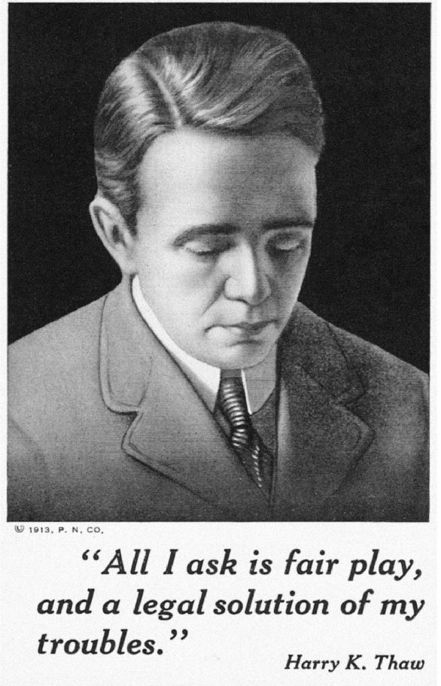

A dejected Harry seeking public support for release from

Matteawan asylum on a postcard, circa 1913.

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN

America’s Pet Murderer

One night, primed with high-ball virtue, he murders a man of genius. Then for years the courts are full of his fame, and the lawyers of his money. . . . At length the long ignominious drama is ended. The paranoiac walks forth free . . . the idol of “the populace.” Cheering crowds crush around him. Women weep over him.

—Newspaper clipping, 1915

In all this nauseous business, we don’t know which makes the gorge rise more, the pervert buying his way out, or the perverted idiots that hail him with wild huzzas.

—The Sun, July 1915

[Her] future will be a study for psychologists, for despite her achievements of luxury and marriage, she has the appetites of the Tenderloin.

—New York Evening World, April 14, 1907

Before the second trial, scheduled for the following January, a battle-fatigued Evelyn, teetering at times on the razor’s edge of nervous exhaustion, gathered together the records of every great criminal trial for the last fifty years. “There was invariably a woman in the case, that goes without saying. It was the woman who interested me,” she writes, “the woman guilty or innocent; temptress or victim. She and her future were immensely interesting to me . . . and my discoveries were of a depressing nature . . . for every woman had gone down, down, down. Drink, drugs, the hundred and one wild diversions which eclipse sorrow and soothe heartache had been pressed to service, and the poor light had flickered out dully and miserably. And this without exception . . . Said I to myself, Evelyn Thaw, you shall do better than that.” It was wishful thinking on her part.

With an awful sense of déjà vu hanging over everyone’s heads, the new trial of Harry Thaw began in January 1908. Once again, more than six hundred prospective jurors were summoned in order to find twelve men who could serve. Delmas was gone, having returned to the West Coast half a million dollars richer, with his record intact, since technically he did not lose the case. Another lawyer, Martin Littleton, was engaged as Harry’s head counsel. But the second trial would be significantly shorter than the first. This time, as one newspaper stated, “in a turnabout so fast that it almost snapped your neck,” the Thaw family helped Jerome’s case. Realizing the futility of the outdated “unwritten law” and the weakness of any defense that did not admit to Harry’s tainted mental history, in spite of Harry’s continued protest, his mother and his legal team supported the idea that Harry was insane—temporarily. Once again Evelyn had to recount the sordid details of her ruination and how it “inflamed the burning embers of her unstable husband’s insane hatred for Stanford White.” The trial was once more on the front pages of every newspaper every day for a month. On February 1, it ended. The jury deliberated for twenty-four hours.

But in a year’s time things had changed. After an unprecedented avalanche of publicity that left “not even a pebble unturned,” virtually everyone’s name, whether good or bad, found itself “ground into the dirt.” It was no longer possible to consider anyone involved in the case as innocent, including the lethal beauty who would for the rest of her life be known as “the girl in the red velvet swing.”

This time, thanks to Evelyn’s willingness to “bare her soul and share her awful sins with the world again,” Harry was spared Topsy the elephant’s fate. Instead of going to the electric chair, Harry was acquitted by reason of insanity and sent to the Matteawan Asylum for the Criminally Insane in Fishkill, New York. Evelyn’s reward for saving Harry’s life was to be virtually cut off from the Thaw money. As soon as Harry was judged incompetent, Mother Thaw took over the finances.

Harry meanwhile began a desperate campaign to have himself declared sane.

A week did not go by without Harry having some communication with lawyers who fought to schedule a hearing regarding Harry’s sanity as soon as possible. In the meantime, at Matteawan, Harry was treated with every consideration his wealth could buy. He had a room of his own, all the books and comforts he required, and was given every facility for seeing Evelyn alone, both inside the grim and repressive-looking asylum, and outside, where he was frequently seen tooling around in a touring car with his warders. As she described her feelings for Harry at the start of his incarceration, “I was sorry for him, and pity retains love even as it creates it.” There were moments during her visits when old feelings of happier times were rekindled, but as she saw it, “The puny logic of humanity can run with Nature’s scheme just so far.” She felt the uncomfortable pull of obligation and believed that “to have cut him off just because he was a life prisoner of the State . . . would have been wicked . . . cruel.” But she was wrong again.

As months passed with no sign of release in sight, Harry became increasingly moody (even for him) and, as Evelyn described it, hateful to her. He was insistent that she demonstrate her appreciation for all he had done for her. He accused her of not being sufficiently grateful to Harry Kendall Thaw of Pittsburgh for the tremendous sacrifice he had made. With each visit and the swelling sense of the impossibility of leaving the asylum, Harry grew more bitter in Evelyn’s presence. There were times when she wanted to scream at him out of sheer nerves, at the “futility of his talk and the extraordinary absence of any sense of proportion.” As she put it, “The everlasting strain was sapping me, destroying me.”

Harry continued to be his own paranoiac manic-depressive self, “at times in the most exalted mood, full of cheer, jovial, almost optimistic,” then suddenly down “in the depths of despair, ready for death, bitter, reproachful and self-pitying.” There were days when he was buoyed by the letters received from well-wishers and fans, most of them women, although there was a percentage of people looking for handouts and a share in the Thaw fortune as well. One fan, a man, even offered to take his place for him in the asylum.

Evelyn herself received bagfuls of letters and cablegrams daily, because, as she put it, “my affairs were everybody’s affairs.” The temptation to offer advice was irresistible to many who wrote to her, as was their desire to pray for her, a subject that had a “certain disflavor” for her as a result of her yearlong training as a “prayer subject” at Lyndhurst. Others wanted her autograph and most her photograph, while some simply wanted to praise her for her courage and devotion. Then there were the insulting letters, the “outpourings of vicious” people who thought she had escaped punishment for her deeds. But as Evelyn put it, “I had been insulted by experts, and the amateur efforts of lesser people left me unmoved.”

As for Evelyn, she felt she was the one who had made the great sacrifice, but that no one had appreciated it, least of all the Thaws, who gradually cut off all her funds and made her life a misery. Her own position was becoming increasingly desperate and called up the worst memories she had of her childhood. Financially she was on shaky ground, as the money that came to her grudgingly, in small sums, from Harry’s lawyers did so at irregular and seemingly capricious intervals. Her allowance “from Harry and his people” was nothing like the princely sum most imagined she had earned with her “soul searing testimony.” The only relief she had was to sculpt, or as she put it, “model in clay,” something for which she had a real talent, perhaps a greater one than either her acting or singing abilities.

Inevitably, Harry’s resentment turned to absolute hatred, which Evelyn gradually reciprocated to a less obvious degree—at first. As she described it, in the first two years of his incarceration at the asylum, her feelings for Harry were moving more in the direction of “loathing,” as he had become “America’s pet murderer.” In the meantime, Harry pursued his release from the asylum with an angry relentlessness, believing that the formation of a lunacy hearing would find him sane and set him free. Although Evelyn claims that it was not her idea to participate in the weary progression of lunacy hearings that Harry demanded and eventually won over the course of seven years (with the aid of the Thaw money once again), she could exact some revenge herself by simply stating the truth about Harry in hearing after commissioned and costly hearing. He belonged, she asserted with clear-eyed simplicity, in the bug house.

But by the fall of 1909, Evelyn was nearing a nervous breakdown; she was overwhelmed mentally and physically. She saw “history horribly repeating itself” as she imagined a “whole lifetime spent in the choking environment of the courts,” where her mother first met with disaster after her father’s death. Grudgingly attending one after another in a seemingly pointless succession of lunacy hearings at the Supreme Court in White Plains, New York, as Evelyn described it, “To save his life they proved him mad, and now in telling the stories of his madness to keep him locked up, he is lashed into a fury.” But no other evidence, even medical, would be so convincing or damning as Evelyn’s testimony at each hearing in keeping Harry incarcerated. If Evelyn had wanted money from the Thaws, this was not the way to get it. But as she initially tried to tell Mother Thaw and the others, no one could convince twelve people that “a man could be sane all his life and a lunatic for the space of three minutes. ” Even though the discussions of Harry’s delusions were terribly humiliating, “only at intervals did he recognize the humiliation.” He still held to his fantasy of chivalry in spite of so much evidence to the contrary.