American Psychosis (4 page)

Read American Psychosis Online

Authors: M. D. Torrey Executive Director E Fuller

Tags: #Health & Fitness, #Diseases, #Nervous System (Incl. Brain), #Medical, #History, #Public Health, #Psychiatry, #General, #Psychology, #Clinical Psychology

Joe Kennedy’s decision to have Rosemary lobotomized was made after careful consideration. According to one account, “when he was in England he had talked with doctors about a pioneering operation called a prefrontal lobotomy,” suggesting that he was exploring this option in 1940, even before leaving England. The first lobotomy in England would not be done until the following year. Kennedy probably also got information from his daughter Kathleen. In 1941 she had gone to work for the

Washington Times-Herald

and had befriended John White, who was writing a series on mental illness for the paper. According to White, Kathleen quizzed him “rigorously” about it. She would “draw me out on the details—not just draw me out but absolutely drain me.” Later she told him “it was because of Rosemary. She spoke slowly and sadly about it, as though she was confessing something quite embarrassing, almost shameful.”

23

For Joe Kennedy a lobotomy offered a definitive solution to the one problem that had defied him. Rosemary’s retardation had been a source of great frustration to him, for money alone would not fix it. For example, when Rosemary was 10 years old, actress Gloria Swanson, Joe’s mistress at the time, recalled his becoming enraged when he offered to donate money to a hospital “if they would guarantee that it could cure Rosemary,” which, of course, they could not. Joe Kennedy’s frustration in the face of his daughter’s severe mental illness must have been several times greater than that engendered by her mild mental retardation.

24

Thus, in the fall of 1941, Joe Kennedy went to Dr. Walter Freeman to arrange for a lobotomy for Rosemary. Freeman’s office was in the LaSalle Building at Connecticut Avenue and L Street NW and was described as “a palatial penthouse in which patients

waited in a 50-foot-long living room.” Freeman, 45 years old at the time, had graduated from Yale University and the University of Pennsylvania Medical School and had trained in neurology in Europe. He had been raised as an Episcopalian with a Catholic mother and had visited Germany just prior to the outbreak of war. Like Kennedy, Freeman had publicly said many favorable things about Germany, so much so that the Federal Bureau of Investigation in 1942 investigated Freeman’s “patriotism and political beliefs.”

25

For Walter Freeman, Kennedy offered a rare opportunity to do a lobotomy on the daughter of one of the nation’s most powerful and influential men. According to Freeman’s biographer, “he yearned to make an indelible mark on the treatment of the mentally ill.” At the time Kennedy approached him, Freeman was making the final corrections to his book,

Psychosurgery: Intelligence, Emotion and Social Behavior following Prefrontal Lobotomy for Mental Disorders

, which would be published in 1942. Freeman regarded his book as “absolutely necessary to the popularization of psychosurgery.” Freeman was an aggressive self-promoter in trying to get lobotomies established as a standard psychiatric treatment, despite intense criticism from many of his medical colleagues. He even hoped to win a Nobel Prize in Medicine for his work; the award instead went to Moniz in 1949.

26

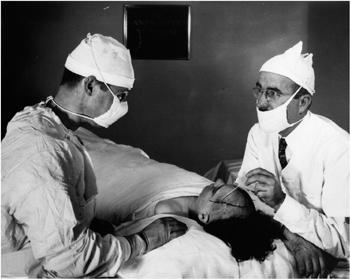

Thus, in mid-November 1941, Rosemary Kennedy was operated on at George Washington University Hospital by Dr. Watts, with Dr. Freeman supervising. Because Freeman was a neurologist and not trained to do neurosurgery, Watts did all the actual procedures until 1945, when the two men parted company. Watts was interviewed in 1994, shortly before his death. As described in Ronald Kessler’s

The Sins of the Father

, Watts confirmed that Rosemary did indeed have a severe mental illness. After mildly sedating Rosemary and drilling two small holes in the top of her skull, Watts inserted a knife and “swung it up and down to cut brain tissue. . . . As Dr. Watts cut, Dr. Freeman asked Rosemary questions. For example, he asked her to recite the Lord’s Prayer or sing ‘God Bless America’ or count backward. . . . ‘We made an estimate on how far to cut based on how she responded,’ Dr. Watts said. When she began to become incoherent, they stopped.” Given Joe Kennedy’s desperation for a definitive solution and his propensity for offering large sums of money to those who might help him solve his problems, it seems reasonable to assume that Drs. Freeman and Watts would have erred on the side of cutting too much rather than too little.

27

And err they did—the lobotomy was an unmitigated disaster. As one family member described it in later years, the operation “made her go from mildly retarded to very retarded.” According to Ronald Kessler, Rosemary could no longer wash or dress herself and was “like a baby.” She had also lost most of her ability to speak: “She is like someone with a stroke who knows what you are saying and would like to let you know

that she knows but she can’t.” This was in stark contrast to the usual descriptions of her as “just chattering all the time” prior to the surgery. In

The Kennedy Women

, Laurence Leamer described the lobotomized Rosemary as “like a painting that had been brutally slashed so it was scarcely recognizable. She had regressed into an infantlike state, mumbling a few words, sitting for hours staring at the walls, only traces left of the young woman she had been” (

Figure 1.5

).

28

The effect of Rosemary’s lobotomy on her family was understandably profound. Rose, who had spent so many hours trying to help her daughter, was devastated. Years later, after Jack and Bobby Kennedy had been assassinated, Rose said that she was “deeply hurt by what happened to my boys, but I feel more heartbroken about what happened to Rosemary. . . . The assassinations hurt, but it was a different kind of hurt.” Eunice, who loved and cared for Rosemary perhaps more than anyone in the family, was probably the most profoundly affected. A student at Manhattanville College in Purchase, New York, at the time, she “began to act strangely . . . and distanced herself even more from life and study at the college. She missed so many classes that one of her schoolmates . . . tutored her in chemistry.” After Christmas recess Eunice abruptly left Manhattanville and transferred to Stanford University. There she was joined by her mother, according to one Kennedy biographer, suggesting that the family was concerned about her. At Stanford, Eunice was remembered as “a silent, sullen presence leaving almost no deep mark on the lives of women with whom she had lived for three years,” suggesting an ongoing depression.

29

FIG

1.5 Neurosurgeon James Watts (left) and neurologist Walter Freeman (right), doing a lobotomy in 1942, a few months after having operated on Rosemary Kennedy. (Harris and Ewing Studio, courtesy of Special Collections Research Center, The George Washington University).

The effect of the lobotomy on Joe Kennedy is difficult to assess because most of his letters have not been made available. According to Amanda Smith, who had access to the Kennedy family files, “almost no mention of Rosemary survives among her father’s papers after the end of 1940. . . . Her correspondence ends, and she seldom appears except obliquely in the surviving family letters and papers.” One letter, however, provides a clue. Written in 1958 to Sister Anastasia at St. Coletta’s school and convent in Wisconsin, where Rosemary had been living for 15 years, the letter said: “I am still very grateful for your help. . . . after all, the solution of Rosemary’s problem has been a major factor in the ability of all the Kennedys to go about their life’s work and to try to do it as well as they can.”

30

* * *

Following her lobotomy, Rosemary was hospitalized for 7 years in Craig House, a private psychiatric hospital in Beacon, New York, best known for having had Zelda Fitzgerald as a patient. Because the hospital was only about 40 miles from Manhattanville College, that may be why Eunice abruptly transferred to Stanford 1 month after the lobotomy, to escape the painful reality of her sister’s condition. In 1948 the Kennedys sought a permanent home for Rosemary and placed her in St. Coletta’s School for Exceptional Children, a convent run by Franciscan nuns, in Jefferson, Wisconsin. Originally, the plan had been to place Rosemary in an institution in Massachusetts, close to her family, but the family was persuaded not to do so because of possible publicity. St. Coletta’s, by contrast, was a thousand miles away in rural Wisconsin. There, on the grounds, the Kennedys built a private house and set up a trust fund to provide for four full-time staff to care for her. She also had a dog and a car in which she could be taken out for rides. In 1983 the Kennedys donated a million dollars to St. Coletta’s, and Rosemary remained there until her death in 2005 at the age of 86.

31

For the rest of their lives, the tragedy of Rosemary would hang over the Kennedy family, like Edgar Allan Poe’s raven:

And the raven, never flitting, still is sitting, still is sitting

On the pallid bust of Pallas just above my chamber door;

And his eyes have all the seeming of a demon’s that is dreaming.

Rosemary essentially disappeared. According to Janet Des Rosiers, Joe Kennedy’s secretary and mistress, “Rosemary’s name was never mentioned in the house. I knew she existed because I saw the family photographs in the attic. But the name was never mentioned.” According to Kennedy biographers who had access to the family’s correspondence, there was “almost no mention” of Rosemary in Joe Kennedy’s correspondence after the lobotomy, as noted above, and Rose Kennedy did “not mention her

again in a letter for the next twenty years.” In addition, according to David Nasaw’s biography of Joe Kennedy, “there is no evidence that anyone in the family either visited or was in contact with Rosemary or the nuns for the first ten or so years” she was at St. Coletta’s. In later years, Rose and other family members did visit, but Joe never did. Evidence of the lobotomy itself also disappeared. According to Walter Freeman’s biographer, “Freeman’s correspondence and private writings are silent on the question of her surgery and its outcome.” It would be 20 years before the family would even publicly acknowledge that Rosemary had been mildly mentally retarded, and no family member has ever publicly acknowledged her mental illness.

32

According to Laurence Leamer’s

The Kennedy Men

, “the lobotomy is the emotional divide in the history of the Kennedy family, an event of transcendent psychological importance.” Plane crashes took the lives of Joe Jr. in 1944 and Kathleen in 1948, and assassinations killed Jack in 1963 and Bobby in 1968, but none of these deaths had as profound an effect on the Kennedy family as Rosemary’s lobotomy had. Plane crashes and assassinations can be viewed as acts of God, but the lobotomy was an act of a Kennedy. Rosemary’s tragedy was a family sin that demanded expiation. That opportunity would present itself in 1960, when John F. Kennedy was elected president.

33

2

ROBERT FELIX: A MAN WITH PLANS

In the fall of 1941, at the same time that Rosemary Kennedy was undergoing a lobotomy in Washington, Dr. Robert H. Felix was writing his master’s degree thesis at Johns Hopkins University School of Public Health in Baltimore, 40 miles away. Bob Felix’s thesis consisted of a plan to fix the nation’s mental illness treatment system by replacing overcrowded state mental hospitals with “properly staffed out-patient clinics” that would “eventually be available throughout the length and breadth of the land.” As a member of the U.S. Public Health Service, Felix believed that such programs should be initiated at the federal level and not merely left up to the states. Twenty years later, the consequences of Rosemary Kennedy’s lobotomy would intersect with Bob Felix’s plan, leading to profound changes in America’s mental illness treatment system (

Figure 2.1

).

1

Felix, 37 years old at the time, had grown up in Downs, Kansas, which had a population of 1,427. His father and grandfather had both been country doctors, so it surprised no one when Felix continued his education at the University of Colorado School of Medicine. Graduating with honors, he then took psychiatric training under Dr. Franklin Ebaugh at the Colorado Psychopathic Hospital, one of a handful of special research psychiatric hospitals in the United States. Ebaugh was an outspoken opponent of traditional state hospitals and a proponent of mental hygiene and community treatment. Felix recalled his training as “one of the most important experiences in my professional career. . . . We were steeped in community psychiatry and a philosophy of public service.”

2