American Psychosis (2 page)

Read American Psychosis Online

Authors: M. D. Torrey Executive Director E Fuller

Tags: #Health & Fitness, #Diseases, #Nervous System (Incl. Brain), #Medical, #History, #Public Health, #Psychiatry, #General, #Psychology, #Clinical Psychology

* * *

On that September morning, as his own political ambitions were being crushed beneath the treads of Hitler’s tanks, Kennedy was also preoccupied with another problem, one that was profoundly personal. The problem was his eldest daughter, Rosemary, who would turn 21 years old in 2 weeks. Recently, he had received disturbing reports that something was wrong with her, something more than the mild mental retardation she had experienced since birth. The retardation had been a source of great distress for the

family, especially for Joe, who expected his children to be strong and accomplished, like himself. Few people knew of Rosemary’s mild retardation, because superficially she looked normal and the family fiercely protected her. As Rosemary grew older, they placed her in convents, where, thanks to Joe Kennedy’s bounteous bestowments on the church’s hierarchy, they could be assured that she would be kept safe and out of view.

At the time, Rosemary was living in a convent in Hertfordshire, northwest of London. The convent trained Montessori primary school teachers, and Rosemary read to the children each afternoon. It was a highly structured environment, in addition to which Rosemary had a full-time female companion, hired by the Kennedys, to watch over her. In recent weeks, however, Rosemary had been exhibiting increasingly severe mood swings and had to be admonished to not be “fierce” with the children. Her recent letters had included “eerie ellipses,” suggestive of an emerging thought disorder. Disturbed by the reports he was receiving from the convent, Joe consulted privately with London’s leading child development specialists. He was perplexed and infuriated by what he was being told; mental retardation had been a family disgrace, but mental illness would be a debacle. Such things could not be allowed in the Kennedy family.

3

With war now a certainty, Joe Kennedy would remain in London as ambassador, but it was necessary to send his wife, Rose, and the children—Jack, Kathleen, Eunice, Pat, Bobby, Jean, and Teddy—back to the States. Joe Jr. was already there, at Harvard Law School. That left only Rosemary, and it was decided to leave her at the convent in Hertfordshire; she was happy there, and it was far from the eyes of the American press. Two months later, reporters from the

Boston Globe

realized that Rosemary had been the only Kennedy child left behind in England and wrote to her, asking for an interview. Joe Kennedy’s aide penned a reply for Rosemary, which she dutifully copied. She said that she “thought it [her] duty to remain behind with my Father.” Further, Rosemary implied that she had responsibilities that necessitated her staying in England. “For some time past, I have been studying the well known psychological method of Dr. Maria Montessori and I got my degree in teaching last year. Although it has been very hard work, I have enjoyed it immensely and I have made many good friends.” The reporters were apparently satisfied and did not pursue the matter further.

4

ROSEMARY’S BIRTH AND DEVELOPMENT

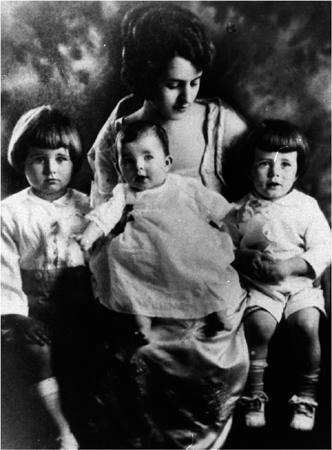

Rosemary had been born on September 13, 1918, at the Kennedy home in Boston. Jack had been born 15 months earlier; Rosemary and Jack were thus closer in age than any other Kennedy children. Joe Jr., the first of the nine Kennedy children, had been born 3 years earlier. As the eldest Kennedy daughter, Rosemary was christened Rose Marie after her mother; the family called her Rosie, but the rest of the world would know her as Rosemary (

Figure 1.1

).

FIG

1.1 Joseph Jr. (left), Rosemary (center), and Jack (left) as young children. Rosemary was born less than 16 months after Jack and the two were closer in age than any other of the Kennedy children. Jack and Joe Jr. were very protective of their younger sister. (AP Photo)

It was an inauspicious time to be born in Boston. Two weeks earlier, cases of influenza had been diagnosed among military personnel awaiting transportation to Europe. The disease spread quickly across Boston, and by September 11 there had already been 35 deaths. The epidemic was unusual in its predilection for young adults, its lethality, and its propensity to cause severe psychiatric symptoms as it spread to the victim’s brain. At the Boston Psychopathic Hospital, Karl Menninger, who had just graduated from Harvard Medical School, was making notes on 80 patients who had been admitted between September 15 and December 15 with influenza and symptoms of psychosis. Menninger would subsequently publish five professional papers on these cases, thereby launching his psychiatric career.

5

Probably of greater consequence for Rosemary was the fact that a milder wave of influenza had passed through Boston the previous spring. According to Alfred Crosby’s history of the epidemic, “flu had been nearly omnipresent in March and April.” This was when Rose Kennedy was in the third and fourth months of her pregnancy. Although it was not known at the time, a later study reported that “maternal exposure to influenza at approximately the third to fourth month of gestation may be a risk factor for developing mental handicap.” Another study showed that the intelligence scores

of individuals who had been in their first trimester of development

in utero

during an influenza epidemic were lower than the scores of individuals born at other times. Even more alarming was a study showing that individuals who had been

in utero

in mid-pregnancy during an influenza epidemic had an increased chance of being later diagnosed with schizophrenia. This specter would later haunt the Kennedy family.

6

Rosemary was said to have been “a very pretty baby” but “cried less” than her brothers had and did “not seem to have the vitality and energy” her brothers had shown. She was not as well coordinated, was unable to manage her baby spoon, and later could not steer a sled down the hill in winter or handle the oars of a rowboat in summer. She tried to join in the games of her siblings and their friends, but “there were many games and activities in which she didn’t participate” and often was remembered as being just “part of the background.”

7

By the end of kindergarten, it was clear that something was seriously wrong with Rosemary when she was not passed to the first grade. Rose Kennedy consulted the head of the psychology department at Harvard, the first of many such consultations. The experts were unanimous in their opinion: Rosemary was mildly retarded. Terms used for such people in the 1920s included “feebleminded” and “moron.” The early 1920s was the peak of the eugenics craze; male morons were said to have a high proclivity toward criminality, and female morons, toward prostitution.

8

Joe and Rose Kennedy determined to prove the experts wrong. From primary school onward, Rosemary was sent to convent schools and provided with special tutors. For example, at the Sacred Heart Convent in Providence, Rosemary was taught in a classroom by herself, “set down before two nuns and another special teacher, Miss Newton, who worked with her all day long.” The Kennedys also “hired a special governess or nurse with whom Rosemary lived part of the time.” When Rosemary was at home, Rose Kennedy spent hours with her on the tennis court, “methodically hitting the ball back and forth to her” and helping her “to write better, to spell, and to count.” The intense work helped Rosemary eventually achieve a fourth grade level in math and a fifth grade level in English, but she could go no farther. To those outside the family, the Kennedys pretended that Rosemary was normal. In

The Kennedy Women

, Laurence Leamer claimed that “even cousins and other relatives beyond the immediate family did not know about Rosemary’s condition.”

9

Among the Kennedy siblings, Eunice, almost 3 years younger, took a special interest in her older sister. Eunice was the most religious of the five Kennedy girls, and “many thought that Eunice would one day become a nun.” She “made a special point of spending time with Rosemary . . . integrating her into their lives.” According to one family friend, “Eunice seemed to develop very early on a sense of special responsibility for Rosemary as if Rosemary were her child instead of her sister.” Ted Kennedy

later recalled, “Eunice reached out to make sure that Rosemary was included in all activities—whether it was Dodge Ball or Duck Duck Goose. . . . Eunice was the one who ensured that Rosemary would have her fair share of successes.” As teenagers the two sisters became close, traveling in Europe together in the summer of 1935. As Eunice later recalled: “We went on boat trips in Holland, climbed mountains in Switzerland, went rowing on Lake Lucerne. . . . Rose[mary] could do all those things—rowing, climbing—as well or better than I. She could walk faster and longer distances than I could. And she was fun to be with.” Like her mother, Eunice was determined to make Rosemary seem as normal as possible.

10

Responsibility for protecting Rosemary also fell to her older brothers, Joe Jr. and Jack, who was closest to her in age. This was especially true as she matured. She was described as “an immensely pretty woman,” according to some observers the most attractive of all the Kennedy sisters, and amply endowed. This, combined with her sweet demeanor and natural reticence, attracted young men, and it fell to Joe Jr. and Jack to warn them off. In summers they would escort her to dances at the Hyannis Yacht Club. As described in

The Kennedy Women

, “Jack put his name at the top of his sister’s dance card and went around the room, getting his friends to help fill out the rest of the card.” When writing to her from college, Jack’s letters were described as “sensitive and warm,” and a biographer described him as being “as generous toward his sister as any of the children.” Rosemary’s problems were thus indelibly etched upon Jack Kennedy’s conscience, as would later become clear when he assumed the presidency.

11

During their first year in London, the Kennedys had continued to include Rosemary in all family social activities. On May 11, 1938, Kathleen, age 18 years, and Rosemary, age 19 years, were presented to King George and Queen Elizabeth in a formal ceremony at Buckingham Palace. A few weeks later, Rose held a coming-out party for Kathleen and Rosemary, complete with 300 guests and an embassy official as Rosemary’s escort. In September, Rosemary joined Eunice, Pat, Bobby, and their governess for a 2-week tour of Scotland and Ireland. Then, in December, Rosemary joined the family for a ski holiday at St. Moritz. According to

The Kennedy Women

, “Rose’s main concern at St. Moritz was her eldest daughter . . . a picturesque young woman, a snow princess with flushed cheeks . . . [who] was attracting the attention of young men who took her cryptic silences and deliberate speech as feminine demureness.” In March 1939, Rosemary joined her family to attend the investiture of Pope Pius XII in Rome, and on May 4, Rosemary was in attendance at the dinner given by the Kennedys for the King and Queen prior to the royal visit to the United States. Thus, until mid-1939, when she was almost 21 years old, Rosemary was very much part of the Kennedy family, protected by them and apparently functioning at a socially appropriate level (Figures 1.2 and 1.3).

12

FIG

1.2 Rosemary (right), with sister Kathleen and their mother Rose, arriving at Buckingham Palace to be presented to the Queen in June, 1938. Rosemary was mildly retarded but 1 year later she developed the initial symptoms of what became a severe mental illness. (Copyright Bettmann/Corbis/AP Images)

A KENNEDY PROBLEM

Rosemary’s status within the family changed during the summer of 1939, as the earliest symptoms of her mental illness became manifest. She remained in England when all of her family, except her father, returned to the United States in September. And when