ence between sacrifice and euthanasia. "So my attorney asked the guy, 'If I had a pet goat on my farm and I take it to you and ask you to put it to sleep and then incinerate it, would you do that as part of your service?' The humane society guy says, 'yes'

|

"And then my lawyer says, 'Okay, if I would take the same goatbut deadbring it to you and say that I was a santero and I had just sacrificed it in a ritual and I would like you to incinerate it, would you do it?' The guy says 'no' And the guy was asked why not, and he says, 'Because that's illegal. I would call the police right then and there because the animal was sacrificed.'"

|

Pichardo pressed one hand to his forehead. One time, he said, he had called the Hialeah waste department to ask if they would pick up chicken carcasses. They wouldn't. Pichardo argued with them, pointing out that the city picked up waste from all kinds of restaurantslobster claws, chicken bones, pork ribswhy not a carcass from the church's dumpster? "But they kept saying no. They wouldn't pick up any carcasses from our waste basket." He smiled almost imperceptibly. "So they can pick up chicken bones over down the street at Kentucky, but can't pick up chicken bones over here."

|

Ricardo, who had been talking quietly with his mother, came over to remind his brother of "a pending appointment." They spoke in low, rapid Spanish for a moment, then Ernesto stood, stretched and stared across the street at a grocery where, he noted, you could buy freshly killed beef, fish or chicken. "It's not about the life of the animals," he said. Justice Kennedy would say, later: "Legislators may not devise mechanisms, overt or disguised, designed to persecute or oppress a religion or its practices."

|

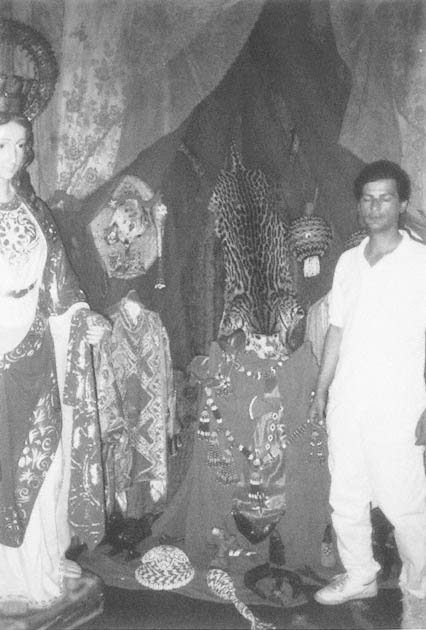

One of the people I had most wanted to see in Miami came from a time before Pichardo, before the Oba, before Ava Kay Jones, before any of them were possible, so to speak. Lydia

|

|