"But even the most intricate experiment requires that by its nature the combination of energies are all working in harmony. If in Haiti, those energies are confused, it isn't going to work, no more than Challenger will work."

|

If the Oba's analysis was correct, the path to restoration of Haiti, and therefore of Little Haiti, lay in increased attention to the gods. But from what I could see of life on the street, and of hints of life behind closed doors, the loa were receiving plenty of care, and if you believed the loa were present even in the many storefront protestant churchesas the orisha were present in the black churches of New Orleansthe spirits were a singularly binding force throughout the community.

|

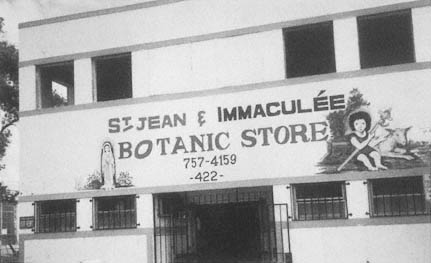

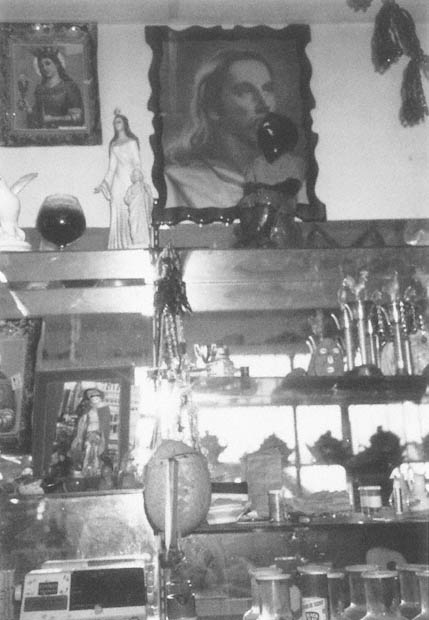

You couldn't drive a block on 54th without running into a church or botanica, or places that seemed combinations of both. One of my favorites was the St. Jean & Immaculée Botanic Store. The bright, hand-drawn mural on the front, depicting a lamb and a young St. Jean Baptiste (John the Baptist as St. John the Infant) perfectly represented a fusion of the two faiths that have been Haiti's legacy since slavery. The store's owner, Immaculée Calitixé, a voudou m'ambo, said the image had appeared to her in a dream. She named her storefront for St. Jean just as Lorita Mitchell had named hers for St. Lazarus and Ernesto Pichardo had named his for Babalu Aye.

|

If St. Jean was the prettiest, Botanica D'Haiti Macaya Boumba was perhaps the busiest on the street. Hand-painted lettering on the coral and yellow front of the store promised a lively inventory: "Religious articles, oil, ensense all kind, perfums, statuettes, variety items, bath. American Specializing in West Indian Produces." It wasn't a botanica, it was a botanica supermarket. Nor was it limited to voudou products. Catholic and Protestant needs, from Bibles to candlestick holders, full stock. Or if you didn't need things of the spirit, you could get bargains in loose-fitting Caribbean shirts, dresses, umbrellas, clocks, cassettes and LPs. Or anything.

|

|