Ancient Iraq (16 page)

CHAPTER 8

The history of ancient Iraq is divided, like its prehistory, into periods characterized by major political changes often accompanied by changes in the social, economic and cultural fields. The first of these periods begins around 2900

B.C.

and ends with the conquest of Sumer by the Semitic king of Akkad, Sargon, in 2334

B.C

or thereabouts. For this reason, it is sometimes called ‘Presargonic’, though the term ‘Early Dynastic’ (abbreviated ED) is usually preferred by English-speaking scholars. The Early Dynastic period, in turn, has been broken down into three parts: ED I (

c

. 2900 – 2750

B.C.

), ED II (

c

. 2750 – 2600

B.C.

) and ED III (

c

. 2600 – 2334

B.C.

), but it must be made quite clear from the start that if by ‘history’ is meant records of political events, or at least genuine incriptions from local rulers, then only part of ED II and the whole of ED III are historical; ED I and the first decades of ED II belong to prehistory in the narrow sense of the term until the chance discovery of an inscription, from one of the earliest kings of Uruk or Kish mentioned in the Sumerian King List, pushes back overnight into the past the beginnings of history, as has already happened twice.

Until the First World War, our knowledge of the Early Dynastic period was almost entirely derived from the excavations carried out by the French at Lagash – or rather Girsu

1

– nowadays Tell Luh or Telloh, a large mound near the Shatt al-Gharraf, forty-eight kilometres due north of Nasriya.

2

Besides remarkable works of art, these excavations have yielded numerous inscriptions which have made it possible to reconstitute in fairly great detail the history of Lagash and to draw up a list of its rulers from about 2500 to 2000

B.C

. Unfortunately, the information thus obtained was practically restricted to one city,

and its rulers did not figure on the King List, probably because they were not considered to have held sway over the whole of Sumer.

Then, in the winter of 1922 – 3, Sir Leonard Woolley found at al-Ubaid, among the debris of magnificent bronze sculptures and reliefs which had once decorated a small Early Dynastic temple, a marble tablet with an inscription reading:

(To) Ninhursag: A-annepadda, King of Ur, son of Mesannepadda, King of Ur, for Ninhursag has built (this temple)

Both A-annepadda and his father figured on the Sumerian King List, the latter being the founder of the First Dynasty of Ur which succeeded the First Dynasty of Uruk. Thus for the first time one of those early Sumerian princes long held as mythical was proven to have actually existed. There is reason to believe that Mesannepadda reigned in about 2560

B.C

.

Finally, in 1959 a German scholar, D. O. Edzard, found in the Iraq Museum a fragment of a large alabaster vase, engraved with three words in a very archaic script:

Me-bárag-si, King of Kish

This monarch, as Edzard showed,

3

was none other than Enmebaragesi of the King List, twenty-second king of the ‘legendary’ First Dynasty of Kish and the father of Agga who, as we have seen, fought against Gilgamesh. Since another inscription of that king was found at Khafaje in an archaeological context suggesting the end of ED II, and since Gilgamesh, king of Uruk, had seven successors whose reasonably long reigns totalled 140 years before his dynasty was overthrown by Mesannepadda, we may safely assume that Mebaragesi reigned around 2700

B.C

. and take that date as a provisional starting-point for the history of ancient Iraq.

The twenty-one kings of Kish preceding Mebaragesi and the four contemporary kings of Uruk preceding Gilgamesh would nicely fill the gap between 2900 and 2700

B.C.

, provided we ignore the incredibly long reign assigned to each of them by the

Sumerian King List. There is no reason to doubt that these monarchs existed, despite the fact that they were later turned into heroes and semigods, but we have no genuine royal inscription from these three centuries, and our knowledge of ED I and ED II is entirely based on archaeological data, the archaic texts from Ur (ED I or ED II) being extremely difficult to understand and of limited historical interest.

From about 2500

B.C.

onwards, however, we have just enough royal inscriptions, as well as economic, legal, administrative and even literary texts – notably from Fara, Abu Salabikh and, later, Girsu

4

– to sketch a rough outline of the political and social history of Sumer. But apart from a few very short inscriptions (mostly kings' names) found at Mari, on the middle Euphrates, and from fragments of inscribed vases and statuettes discovered at Khafaje, in the Diyala valley, all these texts come from southern Mesopotamia, the northern part of this country remaining regrettably illiterate. However, one must not lose all hope, and the thousands of clay tablets recently found at Ebla show us that archaeology may still hold many surprises.

The impact of this discovery cannot be fully appreciated unless one remembers that until 1974 virtually nothing was known about Northern Syria in the third millennium

B.C

. By a stroke of good luck, in that and the following two years the Italian archaeologists who during a decade had been excavating at Tell Mardik – a large mound lying sixty kilometres south-west of Aleppo – brought to light, in the ruins of a palace dated 2400 – 2250

B.C

., some fifteen thousand clay tablets bearing cuneiform signs of the type used in the Sumerian city of Kish.

5

Many words and sentences were written in Sumerian ‘logograms’ but others, written in syllables, left no doubt that Tell Mardik was the ancient city of Ebla – a name that had previously appeared in a handful of Mesopotamian texts – and that the language spoken at Ebla was a hitherto unknown Semitic language, promptly baptized ‘Eblaite’, which to some extent differed from Akkadian and from the West-Semitic languages (Amorrite, Cananaean) of the second millennium

B.C

.

As these tablets were slowly being deciphered, their importance became increasingly obvious. Not only did they reveal that Ebla was the capital city of a relatively large and powerful North Syrian kingdom, but they provided a wealth of information on the organization, social structure, economic system, diplomatic and commercial relations, areas of influence and cultural affinities of this long forgotten kingdom. No Sumerian city-state of the Early Dynastic period has left us such vast and detailed archives, but with a few exceptions (see page

142

) the contribution of the Ebla texts to the history of ancient Mesopotamia, although non-negligible, has up to now remained limited, and as more of these texts are being published, it does not seem that this situation will be greatly modified.

The Archaeological Context

Surface exploration and excavations have shown that at the beginning of the third millennium

B.C.

the urbanization process, which had commenced during the Uruk period, reached its acme, involving the whole of Mesopotamia. In southern Iraq many villages disappeared to the benefit of already large or growing cities, the best example being Uruk which became a huge metropolis covering more than 400 hectares and giving shelter to 40 or 50,000 inhabitants. At the same time, urban centres appeared or developed from proto-historic settlements in the northern part of Iraq. The best known of these towns are Mari (Tell Hariri),

6

half-way between northern Syria and Sumer, Assur (Qala‘at Sherqat),

7

ninety kilometres south of Nineveh (opposite modern Mosul), and others of unknown ancient name but which must have been important: Tell Taya, for instance, at the foot of Jabal Sinjar,

8

and Tell Khueira on the TurkeySyria border, between the rivers Balikh and Khabur.

9

Urban growth, exceptionally coupled with rural proliferation, also occurred in the Diayala basin, north-east of Baghdad, where surveys have revealed the traces of ten major cities, nineteen small towns and sixty-seven villages in a area of

about 900 square kilometres. Incidentally, it is to the American archaeologists who, in the 1930s, excavated three sites in this region, Tell Asmar (Eshnunna), Khafaje (Tutub) and Tell ‘Aqrab, that we owe the classical and sometimes criticized tripartite division of the Early Dynastic period.

10

As a rule, the Mesopotamian towns of the early third millennium

B.C.

were surrounded by a wall, sometimes double and often reinforced by towers. These fortifications bespeak of frequent wars, and this is supported in Sumer by ED III texts mentioning struggles between city-states and against foreign invaders. We shall never know, however, who were the enemies so much feared by the inhabitants of Tell Taya that they built a citadel and raised their city wall on a three-metre high stone base.

With few exceptions, all the northern towns were subjected to varying degrees of Sumerian influence in matters of art, religious architecture and sometimes pottery and glyptics. How this came about remains uncertain. Some authors have postulated the existence of ‘Sumerian colonies’ in the midst of predominantly Semitic populations, but there is no textual or archaeological evidence to support this theory, at least in the Early Dynastic period, and the most plausible carriers of Sumerian culture would be itinerant artisans and merchants.

Most archaeologists agree that the Early Dynastic period culture is issued from the Uruk-Jemdat Nasr culture, and this is true in many respects, but some discontinuities are striking and raise difficult questions. Thus, there seemed in the ED II period to disappear, for an unknown reason, before the end of ED III, a very peculiar and diagnostic building material which has never been used in Mesopotamia before and after: the so-called ‘plano-convex’ bricks, shaped like flat-based bread loaves, laid on their edges and arranged in a herring-bone pattern. A more important problem is the quasi-total abandonment of the classical ‘tripartite’ Mesopotamian sanctuaries and their replacement by temples and shrines of various plans and sizes,

11

some of them often indistinguishable from the surrounding houses

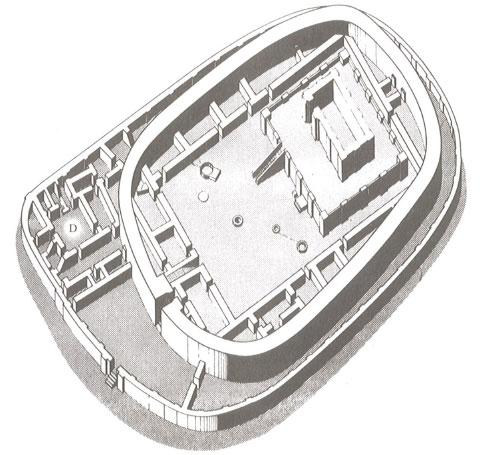

until one went inside, others standing alone, like the large and splendid ‘oval temple’ of Khafaje, with its two eccentric enclosures and its

cella

raised on a platform; this type of temple goes back to the Uruk period (oval temple of Tell ‘Uqair). Some Early Dynastic sanctuaries clearly reflect non-Mesopotamian influences, possibly for geographical reasons. At Mari, for instance, the temple of the local goddess Nini-zaza contained a conical monolith, a

baetyl

, which would have been at home in an open-air West-Semitic temple of Syria or Palestine. Further north, the multiple temples of Tell Khueira, so near to the present Turkish border, rest on stone bases and have open porticoes that are reminiscent of Anatolian dwelling-houses.

Apart from a few interesting wall-plaques, some of them inscribed, and pieces such as the celebrated ‘Stele of the Vultures’ from Girsu, the sculpture of that period is represented mainly by statues of worshippers which once stood on the brick benches that ran around the

cella

of most temples. Usually upright but sometimes seated, their hands folded in front of their chest, these long-haired or bald, shaven or bearded men wearing the traditional Sumerian woollen skirt, and these women wrapped in a kind of saree were staring at some divine statue with their shell-and-lapis eyes set in bitumen – the eyes we have already encountered at Tell es-Sawman two and a half millennia ago. But these statuettes are not all of the same quality.

12

Those found at Tell Khueira are rather crude and clumsy, those discovered in the archaic Ishtar temple at Assur are mediocre, and those, widely publicized, which come from the ‘square temple’ of Tell Asmar are stiff, angular and, with their huge, haunting eyes and their corrugated beards, more impressive than beautiful. In contrast, many of the statues unearthed at Mari are marvellous portraits extremely well-carved, but Mari is very far from Sumer and these remarkable sculptures cannot be regarded as being representative of Sumerian art: in all probability, they were the work of local artists drawing their inspiration from Sumer, the ancestors of the great sculptors of the Akkad period. What is strange is that

The oval temple at Khafaje, Early Dynastic III period. The two areas enclosed by walls measure 103 × 74 and 74 × 59 metres respectively. We do not know to which god or goddess this temple was dedicated.

From P. Amiet

, L‘Art Antique du Proche-Orient,

1977; after P. Delougaz

, The Oval Temple at Khafaje,

1940

.

the statues of worshippers discovered at Nippur and Girsu, in the Sumerian heartland, give the impression of being mass-produced and cut a sorry figure when compared with the masterpieces of the Uruk period. Were they made in workshops for ‘impoverished pilgrims’,

13

or do they reflect the inevitable decline that seems to follow all exceptional periods in the history of art?

To be fair, it must be said that in other fields the art of the Early Dynastic period was far from being decadent. Thus, in a limited area of central Mesopotamia there flourished, in ED I, an attractive polychrome pottery called

scarlet ware

clearly derived from the Jemdat Nasr ware. On the other hand, many sites of the upper Tigris valley and the Khabur basin have yielded samples of the very elegant ‘Ninevite 5' ceramic, at first painted, then heavily incised, and remarkable for its shapes: tall fruit stands with pedestal bases, high-necked vases with angular shoulders, carinated bowls.

14

The scarlet ware was short-lived, the Ninevite 5 ware vanished towards the middle of ED III after a very long existence, and both were replaced, throughout Mesopotamia, by an unpainted pottery with very few artistic qualities.

The art of the stone-cutter followed a contrary course towards improvement.

15

The short and narrow cylinder-seals of the ED I period bearing monotonous friezes of schematized animals or geometric designs (the so-called ‘brocade’ style) were replaced, in ED II and III, by longer and wider seals with totally different compositions depicting either ‘banquet scenes’ or ‘animal-contest scenes’. The former showed men and women drinking from cups or from tall jars through a tube. The latter consisted of cattle attacked by lions and defended by naked heroes and bull-men. There were also some religious motifs, such as the sun-god on a boat. As time went by, the compositions remained basically the same, but they were executed with greater skill. Some seals, notably those of kings, were made of lapis-lazuli or other semi-precious stones, or even of gold, and they were sometimes capped with silver at both ends. An important novelty was the appearance, at Ur, Jemdat Nasr and Uruk, of the first short cuneiform inscriptions on cylinder-seals.

However, it is in metal work that the Sumerians made the most striking advances due to a great extent to the introduction of two new techniques:

cire perdue

(lost wax) for bronze and

repoussé

for precious metals. As we shall see in going through the marvellous pieces found in the Royal Cemetery of Ur, the Early

Dynastic period was the time when the art of the goldsmith reached a degree of proficiency unequalled in any other contemporary civilization. But the raw material had to be imported and paid for with what southern Mesopotamia could offer: cereals, hides, wool, textiles, manufactured objects and bitumen. How, then, were the Sumerians organized to run their economy? What was their social structure? Who were their rulers and what can we know of their political history? To try to answer these questions (and some others) we must leave archaeology and turn to the few texts that are available.