Are Lobsters Ambidextrous? (29 page)

Read Are Lobsters Ambidextrous? Online

Authors: David Feldman

So the “deleted” files are no more erased than the music on an audiotape or television program on videotape that hasn’t been recorded over.

Submitted by an anonymous caller on the Jim Eason Show, KGO-AM, San Francisco, California

.

When

did wild poodles roam the earth?

The thought of wild poodles contending with the forbidding elements of nature makes us shudder. It’s hard to imagine a toy poodle surviving torrential rainstorms or blistering droughts in the desert, or slaughtering prey for its dinner (unless its prey was canned dog food). Or even getting its haircut messed up.

For that matter, what animals would make a toy poodle its prey in the wild? We have our doubts that it would be a status symbol for one lion to approach another predator and boast, “Guess what? I bagged myself a poodle today.”

If something seems wrong with this picture of poodles in the wild, you’re on the right track. We posed our Imponderable to the biology department of UCLA, and received the following response from Nancy Purtill, administrative assistant:

The general feeling is that, while there is no such thing as a stupid question, this one comes very close. Poodles never did live in the wild, any more than did packs of roving Chihuahuas. The

present breeds of dogs were derived from selective breeding of dogs descended from the original wild dogs.

Sally Kinne, corresponding secretary of the Poodle Club of America, inc., was a little less testy:

I don’t think poodles ever did live in the wild! They evolved long after dogs were domesticated. Although their exact beginnings are unknown, they are in European paintings from the fifteenth century [the works of German artist Albrecht Dürer] on to modern times. It has been a long, LONG time since poodles evolved from dogs that evolved from the wolf.

Bas-reliefs indicate that poodles might date from the time of Christ, but most researchers believe that they were originally bred to be water retrievers much later in Germany. (Their name is a derivation of the German word

pudel

or

pudelin

, meaning “drenched” or “dripping wet.” German soldiers probably brought the dogs to France, where they have traditionally been treated more kindly than

Homo sapiens

. Poodles were also used to hunt for truffles, often in tandem with dachshunds. Poodles would locate the truffles and then the low-set dachshunds would dig out the overpriced fungus.

Dog experts agree that all domestic dogs are descendants of wolves, with whom they can and do still mate. One of the reasons it is difficult to trace the history of wild dogs is that it is hard to discriminate, from fossils alone, between dogs and wolves. Most of the sources we contacted believe that domesticated dogs existed over much of Europe and the Middle East by the Mesolithic period of the Stone Age, but estimates have ranged widely—from 10,000 to 25,000

B.C

.

Long before there were any “manmade” breeds, wild dogs did roam the earth. How did these dogs, who may date back millions of years, become domesticated? In her book,

The Life, History and Magic of the Dog

, Fernand Mery speculates that when hunting and fishing tribes became sedentary during the Neolithic Age (around 5000

B.C

.), the exteriors of inhabited caves were like landfills from hell—full of garbage, animal bones, mollusk and crustacean shells and other debris. But what seemed

like waste to humans was an all-you-can-eat buffet table to wild dogs.

Humans, with abundant alternatives, didn’t consider dogs as a source of food. Once dogs realized that humans were not going to kill them, they could coexist as friends. Indeed, dogs could even help humans, and not just as companions—their barking signaled danger to their two-legged patrons inside the cave.

This natural interdependence, born first of convenience and later affection, may be unique in the animal kingdom. Mery claims our relationship to dogs is fundamentally different from that of any other pet—all other animals that have been domesticated have, at first, been captured and taken by force:

The prehistoric dog followed man from afar, just as the domesticated dog has always followed armies on the march. It became accustomed to living nearer and nearer to this being who did not hunt it. Finding with him security and stability, and being able to feed off the remains of man’s prey, for a long time it stayed near his dwellings, whether they were caves or huts. One day the dog crossed the threshold. Man did not chase him out. The treaty of alliance had been signed.

Once dogs were allowed “in the house,” it became natural to breed dogs to share in other human tasks, such as hunting, fighting, and farming. It’s hard to imagine a poofy poodle as a retriever, capturing dead ducks in its mouth, but not nearly as hard as imagining poodles contending with the dinosaurs and pterodactyls on our cover, or fighting marauding packs of roving Chihuahuas.

Submitted by Audrey Randall of Chicago, Illinois

.

What

does the “Q” in “Q-tips” stand for?

Most users of Q-tips don’t realize it, but the “Q” is short for “Qatar.” Who would have thought a lone inventor on this tiny peninsula on the Persian Gulf could have invented a product found in virtually every medicine cabinet in the Western world?

Just kidding, folks. But you must admit, “Qatar” is a lot sexier than “Quality”—the word the “Q” in “Q-tips” actually stands for.

Q-tips were invented by a Polish-born American, Leo Gerstenzang, in the 1920s. Gerstenzang noticed that when his wife was giving their baby a bath, she would take a toothpick to spear a wad of cotton. She then used the jerry-built instrument as an applicator to clean the baby. He decided that a readymade cotton swab might be attractive to parents, and he launched the Leo Gerstenzang Infant Novelty Co. to manufacture this and other accessories for baby care.

Although a Q-tip may seem like a simple product, Gerstenzang took several years to eliminate potential problems. He was concerned that the wood not splinter, that an equal amount of cotton was attached to each end, and that the cotton not fall off the applicator.

The unique sliding tray packaging was no accident, either—it insured that an addled parent could open the box and detach a single swab while using only one hand. The boxes were sterilized and sealed with glassine (later cellophane). The entire process was done by machine, so the phrase “untouched by human hands” became a marketing tool to indicate the safety of using Q-tips on sensitive parts of the body.

Gerstenzang wrestled over what he should name his new product, and after years of soul searching, came up with a name that, at the time, probably struck him as inevitable but, in retrospect, wasn’t: “Baby Gays.” A few years later, in 1926, the name changed to “Q-Tips Baby Gays.” Eventually, greater minds decided that perhaps the last two words in the brand name could be discarded.

Ironically, although we may laugh about the dated use of the word “Gays,” the elimination of the “Baby” was at least as important. Gerstenzang envisioned the many uses Q-tips could serve for parents—for cleaning not just babies’ ears but their nose and mouth, and as an applicator for baby oils and lotions. But the inventor never foresaw Q-tips’ use as a glue applicator or as a swab for cleaning tools, fishing poles, furniture, or metal.

Even though Chesebrough-Ponds, which now controls the Q-tips trademark, does nothing to trumpet what the “Q” stands for, the consumer somehow equates the “Q” with “Quality” nonetheless. For despite the best attempts from other brands and generic rivals, Q-tips tramples its competition in the cotton swab market.

Submitted by Dave and Mary Farrokh of Cranford, New Jersey. Thanks also to Douglas Watkins, Jr., of Hayward, California; Patricia Martinez of San Diego, California; Christopher Valeri of East Northport, New York; and Sharon Yeh of Fairborn, Ohio

.

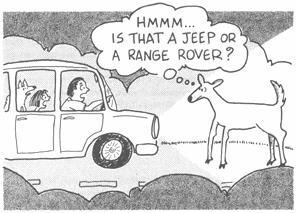

Why

do deer stand transfixed by the headlights of oncoming cars? Do they have a death wish?

Although no zoologist has ever interviewed a deer, particularly a squashed one, we can assume that no animal has a death wish. In fact, instinct drives all animals to survive. We asked quite a few animal experts about this Imponderable, and we received three different theories, none of which directly contradicts the others.

1.

The behavior is a fear response

. University of Vermont zoologist Richard Landesman’s position was typical:Many mammals, including humans, demonstrate a fear response, which initially results in their remaining perfectly still for a few seconds after being frightened. During this time, the hormones of the fear response take over and the

animal or person then decides whether to fight or run away. Unfortunately, many animals remain in place too long and the car hits them.The self-defeating mechanism of the fear response is perpetuated because, as Landesman puts it, “these animals don’t know that they are going to die as a result of standing still and there is no mechanism for them to teach other deer about that fact.”

2.

Standing still isn’t so much a fear response as a reaction to being blinded

. Deer are more likely to be blinded than other, smaller animals, such as dogs and cats, because they are much taller and vulnerable to the angle of the headlight beams. If you were blinded and heard the rumble of a car approaching at high speed, would you necessarily think it was safer to run than to stand still?3.

The freeze behavior is an extension of deer’s natural response to any danger

. We were bothered by the first two theories insofar as they failed to explain why deer, out of all disproportion to animals of their size, tend to be felled by cars. So we prevailed upon our favorite naturalist, Larry Prussin, who has worked in Yosemite National Park for more than a decade. He reports that deer and squirrels are killed by cars far more than any other animals, and he has a theory to explain why.What do these two animals have in common? In the wild, they are prey rather than predators. The natural response of prey animals is to freeze when confronted with danger. Ill-equipped to fight with their stalkers, they freeze in order to avoid detection by the predator; they will run away only when they are confident that the predator has sighted them and there is no alternative. Defenseless fawns won’t even run when being attacked by cougars or other predators.

The prey’s strategy forces the predator to flush them out, while the prey attempts to fade into its natural environment. Hunters similarly need to rouse rabbits, deer, and many birds with noises or sudden movements before the prey will reveal themselves.

Prussin notes that in the last twelve years, to his knowledge only one of the plentiful coyotes in Yosemite National Park has been killed by an automobile, while countless deer have been mowed down. When confronted by automobile headlights, coy

otes will also freeze but then, like other predators and scavengers, dart away.Although deer may not be genetically programmed to respond to react one way or the other to oncoming headlights, their natural predisposition dooms them from the start.

Submitted by Michael Wille of Springhill, Florida. Thanks also to Konstantin Othmer of San Jose, California; and Meghan Walsh of Sherborn, Massachusetts

.