B004YENES8 EBOK (23 page)

Authors: Barney Rosenzweig

On my writing duo’s plus side was their indefatigability, affability, work ethic, and desire to please. It counted for much. Nevertheless, I still continued my search for deeper, richer, fuller, better, believing that the writing would provide the key to that. I forced myself to get back in the swing of things, to realize that, yes, after all I’d been through, I still had to make a show. I spent more and more time with the writers, the film editors, and late at night with Sharon and Tyne. An interesting pattern developed that impacted heavily on our writing style.

At the end of our minimum twelve-hour shooting day, Sharon and Tyne would sign off the clock and repair to their respective dressing rooms to shower and remove their makeup. They would then convene in one or the other’s motor home for a hug as a demonstration of solidarity, a quick drink to celebrate the day’s work, a joke or two, and they would then address themselves to the next day’s eight-plus pages of dialogue.

Somewhere in the middle of the second drink, I would be summoned from my office to join them. They were, of course, critical of the writing or occasionally confused by the intent of a scene. I would ask to hear it once, as written. They would try to get through “this shit,” but invariably got hung up on a phrase, a speech, or an attitude that was bothering them.

I would hear all of this, make whatever points I felt were necessary for the meaning of the piece, and then begin to make minor adjustments in the scenes themselves. With each successive pass through, they became more familiar with the essence of what was there on the page and therefore more and more able to communicate an idea with less and less verbiage.

I have been quoted as saying that on

Cagney & Lacey

our best writing was done with an eraser. It was to this process that I referred. That is what was transpiring in those motor home meetings. Cutting, erasing, and making the scenes less and less verbal and more and more elliptical by using fewer words as the actors became more immersed in, and familiar with, the material.

You could never begin by writing this way, for the actors, or any other reader for that matter, wouldn’t have a clue as to what the scene was about. But now, by making our two stars part of the process, it became their own. And in the hands of two such talented performers as Sharon Gless and Tyne Daly, the results were something to watch indeed.

These sessions would generally end between midnight and one am. I would leave the rewritten pages for Peter to put through in the morning when he got in, usually attaching a note telling him what an extraordinary experience he had missed. It was what I imagine the theater to be at its best. It was stimulating, exhilarating, and inspiring.

Departing Lacy Street was like leaving home and family. Every night I would have to adjust to my real-life relations, who seemed almost like acquaintances compared to the kith and kin of

Cagney & Lacey

. The good news at my “real” home was that Corday basically understood... she not only knew the demands of the job, but there was also the very real fact that she was at least as busy at her own job as I was at mine.

At the same time, I lived in dread of our first episode airing and the nation’s press wondering—in print—just what all the fuss was about. How embarrassing all this would be if, after all the hoopla (with which I was so personally identified), it all came out to be just another show.

At the Beverly Hills Hotel where the announcement was made by CBS chief Harvey Shephard that a mistake had been made and that

Cagney & Lacey

would be back.

Photo: Rosenzweig Personal Collection

Chapter 25

AGAIN WITH THE LIGHTS AND SIRENS

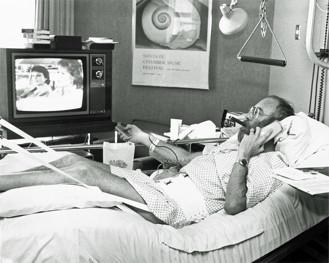

The subject of pressure brings this narrative to Cedars-Sinai Hospital in Los Angeles. I was taken there by ambulance in late February 1984, midway through production of our fifth episode

42

and only weeks before our March 19 premiere on CBS .

Somehow I had herniated a disc in my fifth lumbar in the lower part of my back, a stress -related incident if ever there was one. I wound up being in traction and receiving physical therapy from the hospital for twelve full days.

Video equipment was installed in my hospital room, along with an extra phone line. From my hospital bed I continued my work, complete with writer consultations, casting conferences, editorial notes, and network meetings.

By the third day in traction at the hospital, most of the people on

Cagney & Lacey

had called, save for Sharon, who had sent a sweet note and flower (a simple yellow rose), and Tyne, who, to my surprise, sent a note via my worthy assistant, PK Knelman. It was a lovely, and loving, note. It was hard to keep up with Tyne’s moods; the swings were enormous. I did appreciate the pressure she must have felt. Lord knows I felt it.

Several nights a week, I would work in the hospital on our video equipment with PK from 6 to 11 pm. I would give her my notes to pass on to the editors on three episodes (“Matinee,” written by Chris Abbott, directed by Karen Arthur; “Partners,” written by Patricia Green and directed by Joel Oliansky; and “Baby Broker,” written by Terry Louise Fisher and directed by John Patterson). They were all good shows, but “Baby Broker” was a stunner. I wanted it to open our season.

By the end of my first week in the hospital, CBS began filling the void. They admitted “Baby Broker” was a good episode, but they didn’t think it was commercial enough to be first to air. We were back to talking lights and sirens again. They could not—would not—heed what this show was about.

It was difficult, if not impossible, for me to make this fight from my hospital bed. No one was at those screenings who could tackle Shephard. He and Tony Barr wanted “Matinee” to go first (not so terrible, it was a solid episode). What was disturbing was that they couldn’t see the sell in “Baby Broker.”

It had all the elements of those ABC exploitation M.O.W.s that knocked us off the air in the first place. I was concerned, and the staff was now getting nervous, about the network’s reaction to our script for episode seven. It was good but very light on lights and sirens.

We were all getting a bit paranoid that CBS was still looking for a cop show here. I could win this fight, I thought, if I could just get out of traction and on my feet.

Episode seven, “Choices,” written by Terry Louise Fisher and directed by Karen Arthur, is my personal favorite episode of the 125 we made. It was our biological clock show and came about as a result of conversations with Corday and her best friend, Ann Daniel, who was then approaching her fortieth birthday. Ms. Daniel was childless and confronting that very same timing issue in her own life. I decided that if, indeed, these seven audition episodes were to be our last, we were not going to have a body of work of nearly thirty hours of prime-time programming—featuring a single, childless, working woman in her late thirties—without exploring this issue.

Weeks before my hospitalization, I had talked with Peter and Terry about this, and, at my insistence, Terry agreed to write the episode herself. One obvious issue needed to be addressed. Should

Cagney & Lacey

be renewed for the following year, we most definitely did not want Cagney to have a child. Marriage was out of the question for the same reason. We wanted to continue to explore the relationship of contrasts we had already begun to enjoy with Christine and Mary Beth. It would be counterproductive, we felt, to have them lead similar lives.

If she was not going to have a child, what would happen vis-à-vis her pregnancy, as dictated by the biological clock idea? We felt abortion was too big an issue for us to handle in one episode, and one—we thought—was, quite possibly, all we had left. It was also doubtful that at the time we could have won network approval for a Cagney decision to abort, which is what we felt she would have done, despite her upbringing as a Catholic.

Having her do what Hollywood heroines had done for years (fall down a flight of stairs and miscarry) was something we longed to avoid. What then? Well, initially, I had a glib solution.

Carl Lumbly, who was the actor who played Detective Marcus Petrie, had, as mentioned earlier, been “lost” to the series during the negotiating process. His feelings had been hurt at what he considered a slight, which, in fact, was really only Orion’s typically poor attention to the artist’s psyche. I was eventually able to woo him back, but only on one condition: his return would be for these seven episodes only and that it would be his option alone as to whether he would return beyond that. My “sell” to Lumbly had been that rather than simply have Petrie disappear, why not work a few weeks more, continue in the ensemble he had been part of from the beginning, and assure himself of an episode that would deal with his leaving the show—maybe even complete with a terrific death scene? What actor could resist that?

So, my solution to Terry was simple: “Let’s find a way, an excuse, for Cagney to be temporarily teamed with Petrie on a particular case. It should be a real simple case with easily recognizable bad guys. In the third or fourth act, there’s a terrific chase. Petrie drives, and Cagney rides shotgun. Our detectives’ car goes out of control. Petrie is killed; Cagney is injured. A by-product of that injury is that Cagney miscarries. But the obvious melodrama is masked by the tragedy that has occurred to a fellow officer and one of our regulars.”

Terry bought it. So did Peter. She went off to work out all the story beats and a week later was back in my office in dismay. First off, Carl Lumbly had exercised his option in an unexpected way; he had decided to return with us should the show be picked up. He did not want Petrie to die. That would be the least of it. The network would be yet another, more powerful, county heard from.

Tony Barr had unequivocally turned down the idea that Cagney be pregnant. This was network television in the 1980s, and, if CBS had yet to allow us to have the sound of a toilet flush in the women’s room, they were (if nothing else) being consistent in making this demand.

Cagney’s pregnancy was totally unacceptable to Mr. Barr, and, as head of current programming for CBS and an important spokesperson for that network, he would not be moved. Barr had reluctantly accepted the fact that Cagney (in a pre-AIDS era) was a healthy, aggressive, heterosexual female with many sleepover boyfriends, but, quite obviously, he was not the least bit interested in dealing with the potential consequences of that kind of behavior.

I called Tony myself. I listened and, while disagreeing, understood the depth of his feeling on this issue. I believed it would be counterproductive to attempt an end run here by going directly to Shephard as I had occasionally done in the past.

(Every CBS executive knew of the relationship I had developed with their chief and the entree I had to him. It was a gun I generally kept holstered, but a weapon nonetheless. For Tony to confront me so solidly on this indicated that to go over his head would quite possibly bring an end to our working relationship.)

I suggested a compromise. “What if Cagney only thinks she’s pregnant?”

Barr was a bit nonplussed. “Not even for most of the play,” I continued, “only Act One and a small part of Act Two.” I went on to briefly indicate how I thought it was morally wrong for us to have this franchise and not deal with an issue that women—especially working women—were forced to face every day.

Barr graciously accepted the offer. Call it compromise, call it face-saving— whatever, we had a “deal.” Terry Louise was apprehensive, inquiring, “What am I supposed to do with this?”

I was on my game. First of all, we had to change the story anyway, since Lumbly had opted to breathe life back into Marcus Petrie. What we should go for now, I urged, was one of our real, moral dilemma/emotional shows.

Experience had taught us that in doing that it was best to keep the cop story simple. I referred to April Smith’s script on “Recreational Use.” “Use that caper!”

Both Peter and Terry looked at a loss.

“It’s a year and a half later. The case from that show is finally coming to trial. Do the courtroom stuff you did so well in “Open and Shut Case.”

The very pragmatic Ms. Fisher had a question: “What about Cagney’s pregnancy?”

My rejoinder was rapid fire: “Act One, maybe even part of Act Two, is the same as you had... all the same beats, all the same concerns. Cagney and the audience believe she is pregnant. Should she, should she not have the child? Does she want to marry? Her anger at being forced to decide now, her fear of what it does to her career, of the men at the precinct finding out, her embarrassment at the drugstore where she purchases the pregnancy test, all of that remains for us.”

“Then she finds out she’s not pregnant,” Terry said without enthusiasm.

“Right!” I cheer-led, “And she speculates on what might have been and how she

feels

about all that.”

“Hardly a page-turner,” was the response from my distaff writer.

“Let me tell you something, Terry. That’s where you’re wrong. This is the stuff that makes episodic television great. You can’t do what I’m talking about in a movie or a movie of the week, but here, in this forum, the audience is vested. They

care

about Christine Cagney. We’ve got ’em. They’ll watch her ruminate on the vagaries of life for an entire episode if we told them to. But here we’re also giving them a story—not to placate them ’cause they don’t need it... we give them a story to show that in the middle of all this, Cagney still has a job. She still has to go to work, and that’s the way it goes for a woman in the workplace in this society.”

“What about Act Four? What’s my finish?”

Ms. Fisher, it would appear, wanted it all. I didn’t miss a beat. “Cagney is not pregnant, and she knows it and has dealt with it. The caper is over, and Cagney and Lacey have carried the day in court. The bad guy is gonna go to jail. They decide to celebrate. They go to a bar and get drunk as they talk about life, love, and babies. We’ll shoot it the last day of our schedule. We’ll use real booze; we’ll use multiple cameras and shoot the shit out of the scene while those two gals get plastered.” (This last detail, arguably, was one of the worst ideas I have ever had.)

Terry saw I was not to be denied; her pad was now open, and she was taking notes. I was drawing on the overlapping period involving my last days with old Malibu girlfriend Jeannine, and my early times with Corday.

“‘Neil called,’ says Cagney.” I now had begun doing imitations of Cagney or Lacey, as the scene called for, employing a modest falsetto and slightly drunken slur as I interpolated both parts.

Terry’s note-taking would get more furious. Lefcourt was the audience.

“‘What did he say?’ Lacey wants to know.

“‘That I’m a cactus.’

“‘I beg your pardon,’ says the very drunk Mary Beth.

“Cagney answers, ‘She’s a fern. I’m a cactus. He says that’s why he loves me. I don’t need any watering at all.’

“‘That bastard,’ slurs Mary Beth.

“Cagney argues, ‘No, no, he’s right. It’s me. I’m all mixed up on …’ whatever. You know, Terry. All the stuff we want to hear her say about her life.”

“Then what?” asked my reluctant author.

“When she starts to get down about her ambivalence,” I continued, “Lacey chimes in—ever the optimist.” (Again I did my vocal imitation of the drunken duo as Terry scribbled her notes).

“‘No, no, Chris. Don’t you see you’ve given the thoughts sound—sound and air. Now you’ll be able to deal with it all!’

“There’s a long silence.” I took a grand pause, let it all sink in. “No one says anything,” I continued. “Lacey can’t stand it. ‘So whaddaya gonna do?’

“‘Huh?’ asks Cagney.

“‘Whaddaya gonna do?’ Lacey demands.

“Cagney takes a long beat, takes a swig from her drink, and then, with a twinkle in her eyes, says, ‘I’m gonna do just what Scarlett O’Hara would do. I’m gonna think about it tomorrow.’

“Cagney smiles, Lacey smiles, they clink glasses, freeze frame, end of episode.”

Terry put down her pencil. I wanted to relax, but I didn’t know if I’d made a sale.

Lefcourt spoke up: “Do you understand what Barney’s giving you the license to do here, Terry? He’s letting you write a one-act play for Christ’s sake.” Terry Louise Fisher slowly nodded her head, and the meeting was over.

It is no coincidence that the only time I played a speaking role in

Cagney & Lacey

was in this episode. It was a vignette I wrote as an introduction to the final drunk scene. I played a stereotypical Broadway producer who storms past the two drunken detectives, irked at his show’s poor notices to the point of exasperation: “Doesn’t anyone know what a producer does?” my character wailed.

Well, hardly anyone.