B004YENES8 EBOK (25 page)

Authors: Barney Rosenzweig

I finally interrupted this onslaught of praise with thanks, disbelief, and a warning. “Tony, you are giving me a loaded gun for next season.”

“I know it,” he said. “God help me.”

Our pickup for the following season was all but confirmed, or was it? Shephard did not promote or advertise the show during its two weeks of pre-emptions, and we went on the air cold in mid-April against opposition that had full-page ads in

TV Guide

. We got a 28 share and took the hour. Normally this would be cause to celebrate. I wondered how much weight Shephard would give to the 7-share drop-off since our last outing. I think it was former MGM’s TV chief, David Gerber, who labeled the term “paranoid producer” a redundancy.

Corday was positive a pickup was imminent and tried to reassure me. “You are renewed with a 35 share or with a 28,” she said. “The only difference is that with a 35, CBS meets you at the airport with a band.”

She was right, of course. My problem was I wanted the band.

Chapter 27

FORGET IT, JAKE, IT’S LACY STREET

With the news of a pickup, we began our preparations for the fall. It would be our first time at Lacy Street with a full season order of twenty-two episodes. It is odd to reflect on just how natural it seemed—to be going back to this place that none of us ever believed could serve as anything like a realistic home base for an ongoing television series.

The concept for a Lacy Street–like place dated back to Toronto and to the original

Cagney & Lacey

M.O.W. Although our budgetary savings in that northern city were more than compensatory for what was then a shallow talent pool in a community not then fully attuned to the needs of the film industry, one of our biggest problems with the move was that stage space, in that municipality, was severely limited. As a consequence, a real building (with enough space and high enough ceilings) was sought. What was ultimately found, a three-story abandoned brick edifice owned by the city, had been the dog pound, a structure that had then been recently gutted, preparatory to being torn down. We prevailed on the city fathers to delay their demolition, and, for one month in April of 1981, the Torontonian home for wayward dogs became Manhattan’s mythical 14th Precinct.

Later that year, when CBS unexpectedly ordered

Cagney & Lacey

to series, we fretted about where to actually make the show. Our Toronto dog pound had since been destroyed. Besides, we felt it would be difficult to try to produce this hurry-up, short-order series by long distance. To some extent that also ruled out actually going to New York, but we never even got to that debate because of the prohibitive cost factor of production in and around Manhattan in that cost-conscious era.

The natural thought was to film the series in Hollywood, but at such late notice it would be difficult (read expensive) to find proper stage space. There was also the matter of construction costs of our requisite number of permanent sets, including, in addition to the various elements of the 14th precinct—squad room, desk sergeant area, Samuel’s office, locker rooms, the ladies’ room—the Lacey household and the Cagney loft.

The one-time furniture/mattress factory that was found, suitably enough on Lacy Street, provided ample space for everything we would need and was (ironically) across the street from the proposed site of the new Los Angeles dog pound. It seemed fated to be ours, but only a Bette Davis reading could have done the place justice: “What a dump.”

We were only going to be there, we thought, for six episodes. We would have to move eventually; the eighty-one-year-old structure could not be properly air-conditioned in the summer nor could the drafty, cavernous interiors be adequately heated in the winter. It leaked. The plumbing was problematic. It was damp and had a significant population of rodents. As soon as we became successful, we said, we would move. Success wasn’t so easy to come by.

Our next order was for thirteen episodes; too few for any sense of permanence. All right, we’d try another season in the hellhole. (Besides, at that time, the writers and producers all worked out of decent offices in West Los Angeles.)

We then received an order for nine episodes to fill out the season. (No time to move now; besides, I had just forced Orion to build cubicles at the old factory for the editors and writers to save me driving time.) Cancellation came next, and with it our return of Lacy Street to the rats. CBS then was to admit their mistake, resulting in a seven-show order and making a homecoming to Lacy Street the only plausible solution. Now, finally, and at last, a full order of twenty-two shows.

Robert Towne’s famous line from

Chinatown

was paraphrased on a large sign put up on the premises by Peter Lefcourt: “Forget it, Jake, it’s Lacy Street.” The idea of finally leaving our (by then) beloved mattress factory was never again seriously discussed.

“Lacy Street” had become a synonym for camaraderie. It reminded me of an observation I had made for the first time as a teenager in the 1950s. The Morris Garage people of Britain had begun to export their classic MG Roadster to Los Angeles in relatively large numbers. It had a rubberized convertible top with isinglass side curtains. On a rainy California night you would be dryer walking to your destination without hat or umbrella than you would be driving in that MG. Those who owned them would touch their horn with a friendly honk when coming upon another of their fraternity; it was in the best tradition of the Knights of the Road.

Years later, when I lived in Malibu and became one of those community activists who fought the real estate developers (by constantly voting against the installation of sewers and extolling the virtues of our country cesspools), I felt a similar comradeship. Neighbors—brothers in adversity—that’s what we were at Lacy Street.

Fifty thousand square feet and everyone who worked there was working on

Cagney & Lacey

; conversely, virtually everyone who worked on

Cagney & Lacey

was—by 1982—there. Unlike a conventional studio operation, there were no extra bodies, no extraneous personnel, no “suits,” no members of other crews (who might stir a pot or two by comparing payroll checks or overtime chores). We were a solid, and solitary, unit.

Since there were no restaurants in the immediate area, we catered meals—breakfast and lunch every day, and many evenings we served dinner as well: twelve-hour minimum days, at least five days per week, working together, eating together, and sharing the adversity of our terribly outmoded facility together.

There was synergy to the place as well in terms of how our pictures were made. If an editor needed a line of dialogue to bridge a cut, it was a short walk to the filming area where he could sidle up to our sound man, Mo Harris, make the request, wait a bit while the line was recorded on the spot, then return to his editing room with the requisite material in hand.

My editorial acumen was enhanced by Lacy Street as the facility, with its proximity to the stages and the actors allowed me not simply to cut a film but rather to rough it in and then, as in the old studio days gone by, order an additional close-up, or a retake, or a new scene with actors we had under contract on sets that were always ready, and all of it right next door.

There was a popcorn machine outside my office that operated nearly around the clock. Grips, technicians, teamsters, actors, editors, writers, and secretarial staff would come by for a snack. Most would stick their head in my office’s open door to greet me with a “Hi, Boss.” There was no Universal tower, no executive suite.

Director Alex Singer was always one of my favorites. It was more than the luck of the draw on scripts that many of our best episodes bore his credit as director. He was a voracious reader, an intellectual, a bit of a philosopher, and a student of offbeat human behavior. I was, therefore, not surprised when he entered my office one morning—popcorn box in hand—and said, “I want you to describe to me, if you will, the essence of the graffiti in the men’s toilets at Universal Studios.”

This was typical Alex. Why settle for hello when a polemic can be posed? I did not wait long before answering: “Racist. Sexist. Homophobic and … pornographic.”

“Excellent,” came Mr. Singer’s response. “And what about Paramount Studios?”

I pondered for only a moment; was this a trick question? I thought not. “The same,” I speculated.

“Correct.” Singer was clearly delighted. “Now,” he asked, “what about the graffiti here at Lacy Street?”

I took a moment. I tried to visualize the walls in the men’s room some three hundred feet from my office. My brow furrowed, and Singer’s patience faded. He made his point as he leaned over my desk, putting his face close to mine and whispered, “There isn’t any.”

He was right.

It didn’t say so much about the crew we had hired—many of whom had probably contributed to the decor of men’s rooms at studios all over town—but what it did address was the way these men felt about the place at which they now worked. It was not a faceless or anonymous monolith. It was ours. It was Lacy Street .

Some months later, I was standing next to Director Singer at our graffiti-less urinals. As we each relieved ourselves, I spoke of how I missed having my own private toilet. It wasn’t something personal against him, or anyone in the company, I quickly added. It wasn’t for sanitary reasons or even my penchant for enjoying some quiet reading time while ensconced on the commode. The real reason I wanted my own toilet was to avoid the walk from my office to the facilities Mr. Singer and I were then occupying. (Not only was the near-football field length a considerable distance from my office; it also meant my having to pass in front of several actors’ dressing rooms, the wardrobe department, the property master’s office, three editing rooms, Dick Reilly’s post-production cubicle, and our screening room. Invariably, as I would attempt to make a beeline from my desk to the head, any number of people would stop me “just for a second,” to see this costume, fabric, prop, piece of film, or just to chat or discuss a dubbing date.)

Singer cut me off. “Barney, you’re a big success now. Do it. There’s that storage space next to your office. It’s on the street side of the building, so tying into the sewer lines will be no big deal. The whole thing could be done quite luxuriously for maybe $10,000. Just do it.”

He was right. I was a success, and, if I wanted this perquisite, I should have it.

A week or so later, Director Singer asked about the progress of my plans for a restroom retreat. I had to tell him I had decided against it. “It smacks of elitism,” I said. “Very un-Lacy Street.”

One did not need to elaborate on such thoughts with Alex Singer.

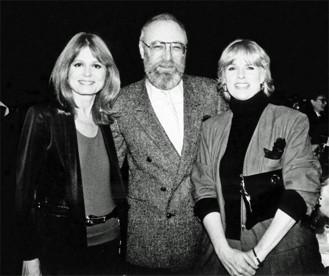

Gloria Steinem, a great friend of our series, on the left and Sharon on the right. Am I a lucky guy or what?

Photo: Rosenzweig Personal Collection

Chapter 28

NO ONE CAN WRITE THIS SHOW BUT ME

The summer of 1984 has to go down as one of the very best of my entire life. The elation and joy of it all coming together so beautifully in the spring of that year did not subside. Letters of thanks and congratulations poured in from all over the world for, by this time, the series had made its debut in Canada, Australia, and England—where it became an instant smash hit. The summer was one of the very best, but not without its challenges.

My concerns about the staff—Lefcourt, Fisher, and newcomer (to us) E. Arthur Kean— were somewhat allayed by the return of Steve Brown. Steve’s organizational skills are substantive, and this became all the more important to me as I increasingly occupied my time with the fringe benefits of my new celebrity.

Both of Corday’s pilot projects for Columbia failed to get picked up, and she found to her dismay that she was not even allowed proper mourning time. After all, how many hits did any married couple need? The assumption that my wife and I had now joined an elite echelon of the super rich, with a syndicatable show, was given voice in our social circle. There was open speculation that we were now millionaires with perhaps $30,000 to $50,000 per episode in retroactive guaranteed advances. If they only knew the truth of our deals, Corday might have received a sympathetic condolence or two on the demise of her pilots.

Meanwhile an old cloud came back on the horizon. CBS miscounted and gave Sharon top billing over Tyne in the ads for one of our episodes for which it was Tyne’s turn. Ms. Daly was on the rampage again, but that summer at the fiftieth birthday party for Gloria Steinem at the grand ballroom of the Waldorf-Astoria in New York, I took a few minutes to talk to her, and she seemed to understand the plausibility of human error on the part of CBS. For a while, anyway, she dismissed her latest conspiracy theory.

Near the start of production for l984–85, only weeks after ending our short seven-show season, Tyne was in a curiously ebullient mood while Sharon was tired and in a terrible funk. Lefcourt had referred to it as the “cuckoo clock syndrome”: when one bird was out, the other would be in; they were never in the same place emotionally at the same time.

In the midst of this and while preparing other projects for her own

Can’t Sing, Can’t Dance

Company at Columbia Studios, Corday phoned to say that, for old time’s sake, she and her erstwhile partner, Barbara Avedon, would like to do a script for the show... actually, two scripts.

What they visualized was a two-part episode dealing with Mary Beth Lacey’s discovery that she had a cancerous tumor in her breast. Avedon’s ex-husband, Mel, was a well-known oncologist, and I was pitched by Corday that there was much new information for women that was not getting out about the virtues of lumpectomy over mastectomy.

I have my own, at best, questioning views of the efficacy of western medicine, so I was excited about the idea from the outset and bought the concept over the phone.

Peter Lefcourt was displeased. The acquisition of new material was his department. He felt that I had breached our arrangement by buying an idea without consulting him.

I tried to assuage his feelings. I acknowledged the correctness of his position, while still holding to my prerogatives, especially when the pitch not only came from my wife but involved the co-creators of the series itself.

“What would you say,” I asked, “if I was Marsha Mason and we were working on

The Odd Couple

series together, and my spouse—Neil Simon—called and said he wanted to write an episode?”

“You should still check with me,” was his response. I shook my head. These kinds of territorial disputes were things I could not take seriously. Uncharacteristically, Peter stewed. I had not heard the end of this.

There were other objections. Terry Louise Fisher did not want to do a medical show; Steve Brown quickly aligned with his former partner, while new writing staff member E. Arthur Kean’s only concern was that the women authors would not know what it would be like to have breast cancer. Really? As if

he

would and

they

wouldn’t? I was getting annoyed.

Avedon and Corday made an appointment to come to the office to break down the story for the writing staff. I elected to attend this conference (something I did not normally do when outside writers were meeting with the staff) and was horrified by what I witnessed.

“If this is the way you treat freelance writers who come to us with their ideas,” I said—primarily to Steve and Terry in the post-mortem that followed the departure of Avedon and Corday, “then I am amazed we have not yet been brought up on charges by the Guild.”

I went on. “Forget the fact that one of these women is your boss’s wife, or that the team that was just in here are the only writers who ever faced a truly blank page on this project. You may even dismiss the fact that because of them you all have jobs paying you well into six figures. But what I don’t get is how you could be that rude or that hostile to ordinary, everyday, fellow professionals.”

They were hardly contrite. I guess you don’t reach their level of success as writers in Hollywood without developing very thick skins. There are a lot of jokes at the Writers Guild of America (WGA) dinners about those insensitive, clod-like producers and prima donna directors. The entertainment committee of the WGA might consider an update of their routines by looking a little closer to home.

Maybe it was a defense mechanism. Maybe, after years of note-taking from producers, directors, stars, and networks, the writer on a television staff gets territorial and really begins to believe the oldest cliché in their handbook, namely, “No one can write this show but me.” Season after season, show after show, it always remains the same: “No one can write this show but me.” Those were the exact words spoken to me by Paul King in 1967 when, at the age of twenty-nine, I took over the

Daniel Boone

series. It was the same phrase said to me by Rick Husky, as he had turned over the reins on

Charlie’s Angels

, and now, though unspoken, it was essentially what was being said by the

Cagney & Lacey

writing staff. And they believed it! They believed it as individuals and as a group. It is one of the things wrong with television.

“Staffthink,” the belief that “no-one can write this show but me,” leads to the homogenization of a series and of television in general while discouraging the freelance writer, the artist with a singular story to tell, that he or she might be able to reveal better and with more passion than anyone. Most staffs are horrified at the thought of opening the doors to outside writers, whom they consider unguideable and less talented than themselves. Because they are writers and not producers (regardless of what credit they may negotiate for themselves), they are, as are most of their fellows in the Writers Guild of America, compulsive rewriters.

And then there is the matter of economics: hiring a freelancer cuts into the staff writer’s income as individual script money, over and above their weekly salaries, now would go to the freelancer instead of them. As a result, a very insular, if not incestuous, situation exists. At its worst, it is repetitive in spirit, in character, and in dialogue. At its best, it is the same, with only good stylistic achievement as a cover. Worst of all, if, as in the early days of television, there are any budding Paddy Chayefskys out there—wonderful, talented, young writers who need encouragement—they will have a hard time getting that from any of those staffing a current TV series.

Obviously this is a Jones

46

for me, going way back in my career from the early days of the creation of the so-called hyphenate. For the most part I maintain a certain amount of equilibrium with the staffs I have hired (forced to hire, really, since the almost-total demise of the freelancer), but there are days when my button on this subject gets pushed. This was one of those days.