B004YENES8 EBOK (21 page)

Authors: Barney Rosenzweig

Chapter 23

COME TO ME/GO FROM ME

Some things do not change: me, for instance. It has been somewhere between twenty and thirty years since much of all of this has happened, and I keep looking for the lesson, searching for the growth. Aside from my waistline, much of it is not readily apparent (at least to this reader). The emotional scar tissue is still, somehow, fresh, and, even where it is not, I do not seem to be able to recount these ancient moments or stories without falling back on my feelings of that time, sans anything resembling perspective.

This can be a good thing in terms of verisimilitude, but overall it is a weakness, especially when (pedagogically) I wish to face the class with the query: “What have we learned?” Not too much, apparently.

I make this digression for more reasons than self-effacement. Richard M. Rosenbloom is one of the kindest, smartest, and most decent human beings I have ever met in my life. He doesn’t come out that way in much of what is to follow. There were times when we were adversaries—maybe only for an afternoon—but the story of that time I only know how to tell with the zeal I felt at that time. Dick Rosenbloom comes out the worst for it, and I am sorry about that.

There are some galley readers who have said some similar things about my treatment of Tyne Daly. I have never loved anyone I have not sired or slept with more than I love Tyne Daly. But, in the early days of our relationship on

Cagney & Lacey

, before we had totally learned to trust one another, she was a piece of work and, on occasion, could be a very major pain in the ass. I just could not effectively alter what I remember, nor do I possess the will to sugarcoat. The brilliant and talented Ms. Daly is, therefore, presented by me warts and all, and I hope she either never reads this book or, if she does, rises above it to forgive me. In my mind, she will always be my star, as she is, very much, the star of this book.

As for everyone else, I am (I fear) at times a bit tough on people I rather liked and a bit too easy on some whom I could barely abide. It is, I concede, an odd sort of attempt at even-handedness and may have occurred because, even though I may have failed, I tried very hard not to write one of those Hollywood books in which no one wants their name mentioned.

Meanwhile, back at those Century City negotiations for the resurrection of

Cagney & Lacey

, Orion had done nothing to address my deal. Sharon Gless pronounced she would not do the show without me, but so much money was at stake that I did not feel comfortable relying on that pledge. Shephard had not reiterated his demand that I be “of the essence,” nor had he withdrawn it.

Orion felt, I suppose, that they could finesse this. After all, I was committed to the show, at least on a non-exclusive basis, for $10,000 per episode; they knew I could no longer threaten to do this from a beach in Hawaii, because they had me under a separate, exclusive television contract for the next two years, requiring my presence in Los Angeles, as opposed to the South Pacific. Since, however, their strategy relied on the existence of both deals, they would, of course, have to pay me under the terms of both deals. I was, therefore, making plenty of up-front money. What I wanted negotiated was justice, in the form of a back-end reward for success.

There was no way I could do the series and devote enough time to properly developing new material. I was, therefore, being asked to give up the opportunity of tremendous upside potential on any new projects I might develop because Orion, the network, and the stars wanted me to devote my full and exclusive time to making

Cagney & Lacey

.

The idea was to get us beyond this seven-show order to the next season, and the next after that, and so on. I wanted to do it. I simply wanted to share in the reward if I was successful. Medavoy said he understood. He had already removed Rosenbloom from the negotiations with me, believing his TV president was too sympathetic to my position. The youngest Orion partner said he would pressure Mace to give me something from his deal, since Mace, after all, wanted to be in the movie business with Orion. It was clear Medavoy was not averse to using his leverage to accomplish this.

“Leave Mace alone.” I glared at Medavoy to emphasize my adamancy. “Regardless of my personal opinion of Mace Neufeld,” I continued, “he negotiated a deal in good faith, and as far as I’m concerned it’s final.” I leaned into the West Coast Orion topper. “I am your responsibility. I’m not interested in Mace’s profit points, which may or may not be worth a quarter. I want the same definition of gross and the same guaranteed dollars that I have in my current deal with your very own company. I am giving up the possibility of having enormous personal success and am doing so for you and for this series. What I am asking you to do is acknowledge that and give me some of your end, without going near Mace. I want it as a settlement—compensation for what I am sacrificing on my new deal.”

Medavoy heard me. He said he would take my plea under advisement, but the result was a stone wall. It was clear that they felt they could rely on my emotional commitment to the show.

Meanwhile, the air date for

This Girl for Hire

drew near. I now had a constituency of thousands of hard-core

Cagney & Lacey

buffs who had proven to be an effective force. I composed a letter on

This Girl for Hire

letterhead to the fans of

Cagney & Lacey

. I explained that the stationery was in reference to a new project brought to them by the same team that had made

Cagney & Lacey

(creators Barbara Avedon & Barbara Corday, writers Steve Brown & Terry Louise Fisher and, of course, yours truly). I wrote that I welcomed their views (as I was sure the network would) as to the project’s suitability as a series.

To make all this a less-than-blatant commercial spiel, I integrated a lot of update information on the progress of the putting together of

Cagney & Lacey

. That’s what I knew they were interested in, that’s what we had in common, and that was what provided a legitimate segue from the results of one lesson in TV democracy to my suggestion of expanding the process to my next project.

You think this lacks subtlety? Paramount didn’t. Gary Nardino had left his post as studio chief, and the team that replaced his refused to pay the less than $1,000 postage bill. “Too much

Cagney & Lacey

,” they exclaimed.

I was in the midst of being crowned the reigning monarch of public opinion manipulation in the television marketplace, and these assholes were giving me a hard time over chump change. I was distracted by my

Cagney & Lacey

problems, disheartened by Paramount’s myopia, and generally tired of fighting. The effort died.

This Girl for Hire

went on the air to very good reviews and reaped a 19 share of audience. It was one of the lowest-rated made for television movies in history.

How I missed Gary Nardino.

37

With all of his bluster, he was always a terrific salesman and a marvelous showman.

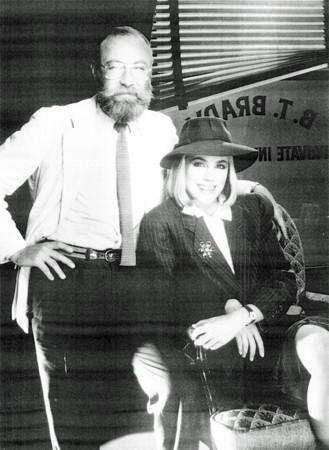

A skinnier me with

This Girl for Hire

star Bess Armstrong. Harry Langdon took the photo, used for an ad in the

Daily Variety

, where I apologized for the lousy ratings.

Photo: Rosenzweig Personal Collection

Meanwhile, on the

Cagney & Lacey

front, agents Merritt Blake and Ronnie Meyer had worked out a new compromise on billing for their respective clients, only to have it renounced by long distance. In a phone call, from her film location in Yugoslavia, Tyne Daly instructed Merritt to “Tell Barney, ‘Barbara was right!’”

(Some weeks before, when we were all flushed with excitement over the CBS call to put it all together again, Corday had facetiously predicted that the whole deal would probably fall apart over billing. Tyne was now saying just that.)

I didn’t know what to do. To wait until Tyne returned from Yugoslavia would surely result in CBS pulling out. I considered flying to the Mace Neufeld location to attempt to talk her into it but thought better of that major piece of aggravation. From my view, the ultimate blow up was near. I felt Tyne was wrong. What was more important was that she believed she was right. No amount of money or concessions would rectify her emotional feelings of righteous indignation.

That very same week, Warner Bros. worked out billing on a Burt Reynolds, Richard Pryor, and Clint Eastwood film. That could be worked out; this could not. It was crazy.

To be fair, though she was being very uncompromising and difficult, Tyne, as usual, had a point of view—something to the effect that “

I saved the show last time by compromising my billing; now it’s Sharon’s turn

.” The flaw in that logic was that it was never “her billing,” but rather a scrivener’s error that, in an unhappier time (the firing of her partner, Meg Foster) had been a wedge she had tried to use (I would guess), to either have us bring back Meg or to release her from her contract.

I focused my energy on trying to convince Sharon to be big about this and give in, pointing out that each of us has a dark side, a part of us that is unreasonable; Sharon has hers, and indeed so do I. The billing thing was Tyne’s. Meanwhile, the really hard work was propping up Dick Rosenbloom and his meager staff at Orion.

They were not a high-powered or sophisticated gang. They were simply not used to playing for these kinds of stakes. Rosenbloom was fatigued. He incorrectly believed that if deals were not wrapped up in a matter of days, CBS would rescind the order. The pressure, the time consumption, the millions at stake, his limited staff, and his own lack of experience in this area were conspiring to inundate him. Orion Television had practically come to a halt. The morning of October 25, we lost our Detective Petrie, Carl Lumbly, and that same afternoon the deal for John Karlen’s Harvey Lacey was almost blown. (The Lumbly loss was later rectified, and our Detective Petrie came back to the show.)

The bottleneck created by

Cagney & Lacey

at Rosenbloom’s office jeopardized at least one of my other projects, and I could only imagine what other Orion contract producers with less access to Rosenbloom were going through. Coupled with this were the normal difficulties of trying to put any project together, plus the emotional and historical complications of this particular project, as well as the ambivalence we all shared about walking away while we were still a hit. Finally, there was my own situation with Orion and how

Cagney & Lacey

complicated my ongoing relationship with them.

It was truly a pressure-packed period, and all the while the press looked on, the letters from fans kept pouring in, and we—quite naturally—had to continue to smile and put a good face on the whole thing.

Leadership was what was required. Orion had plenty of legitimate contenders for the post—Krim, Pleskow, Medavoy—but they were not forthcoming. All those high-priced, high-powered merchants of diplomacy and not a word from any of them. Rosenbloom’s stance, therefore, was to stonewall.

It was left to Tyne’s pal and publicist Marilyn Reese and her friend Monique James from Sharon’s team to try to do something. All I could do was to assure Monique that Rosenbloom was serious; that as little as Orion had contributed in this whole process, they would do no more.

Mmes. Reese and James put Tyne and Sharon together by transatlantic telephone, and the next day I was to learn that the two principals laughed and cried for forty-plus minutes with a compromise being affected.

“It’s all going to work out,” said Monique.

Not quite. Four days later, Tyne told Sharon, via phone from Yugoslavia, that she could not live with herself or digest her earlier agreement to share billing. She apparently went on and on with Sharon about a myriad of other offenses perpetrated against her, most of them by me (including a meant-to-be warm and humorous congratulatory wire I sent regarding “the compromise.” A simple thank-you from me would have sufficed, and I should have known better than to do any more than that).