Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era (134 page)

Read Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era Online

Authors: James M. McPherson

Tags: #General, #History, #United States, #Civil War Period (1850-1877), #United States - History - Civil War; 1861-1865, #United States - History - Civil War; 1861-1865 - Campaigns

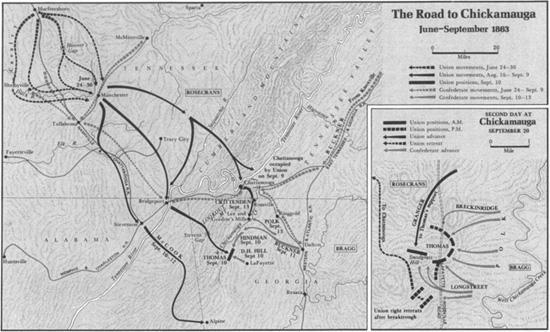

In little more than a week of marching and maneuvering, the Army of the Cumberland had driven its adversary eighty miles at the cost of only 570 casualties. Rosecrans was annoyed by Washington's apparent lack of appreciation. On July 7 Secretary of War Stanton sent Rosecrans a message informing him of "Lee's army overthrown; Grant victorious. You and your noble army now have the chance to give the finishing blow to the rebellion. Will you neglect the chance?" Rosecrans shot back: "You do not appear to observe the fact that this noble army has driven the rebels from Middle Tennessee. . . . I beg in behalf of this army that the War Department may not overlook so great an event because it is not written in letters of blood."

5

Southern newspapers agreed that Rosecrans's brief campaign was "masterful." Bragg confessed it "a great disaster" for the Confederates.

6

His retreat offered two rich prizes to the Federals if they could keep up the momentum: Knoxville and Chattanooga. The former was the center

5

.

O.R

., Ser. I, Vol. 23, pt. 2, p. 518.

6

. Foote,

Civil War

, II, 674, 675.

of east Tennessee unionism, which Lincoln had been trying to redeem for two years. Chattanooga had great strategic value, for the only railroads linking the eastern and western parts of the Confederacy converged there in the gap carved through the Cumberlands by the Tennessee River. Having already cut the Confederacy in two by the capture of Vicksburg, Union forces could slice up the eastern portion by penetrating into Georgia via Chattanooga.

For these reasons Lincoln urged Rosecrans to push on to Chattanooga while he had the enemy off balance. From Kentucky General Burnside, now commanding the small Army of the Ohio, would move forward on Rosecrans's left flank against the 10,000 Confederate troops defending Knoxville. But once again Rosecrans dug in his heels. He could not advance until he had repaired the railroad and bridges in his rear, established a forward base, and accumulated supplies. July passed as General-in-Chief Halleck sent repeated messages asking and finally ordering Rosecrans to get moving. On August 16, after more delays, he did.

Rosecrans repeated the deceptive strategy of his earlier advance, feinting a crossing of the Tennessee above Chattanooga (where Bragg expected it) but sending most of his army across the river at three virtually undefended points below the city. Rosecrans's objective was the railroad from Atlanta. His 60,000 men struck toward it in three columns through gaps in the mountain ranges south of Chattanooga. At the same time, a hundred miles to the north Burnside's army of 24,000 also moved through mountain passes in four columns like the fingers of a hand reaching to grasp Knoxville. The outnumbered defenders, confronted by Yankees soldiers in front and unionist partisans in the rear, abandoned the city without firing a shot. Burnside rode into town on September 3 to the cheers of most citizens. His troops pushed patrols toward the North Carolina and Virginia borders to consolidate their hold on east Tennessee, while the rebel division that had evacuated Knoxville moved south to join Bragg just in time to participate in the evacuation of Chattanooga on September 8. With Rosecrans on his southern flank, Bragg had decided to pull back to northern Georgia before he could be trapped in this city enfolded by river and mountains.

"When will this year's calamities end?" asked a despairing Confederate official on September 13. Desertions from southern armies rose alarmingly. "There is no use fighting any longer no how," wrote a Georgia deserter after the evacuation of Chattanooga, "for we are done gon up the Spout." Jefferson Davis confessed himself to be "in the depths of gloom. . . . We are now in the darkest hour of our political existence."

7

But it had been almost as dark after Union victories in early 1862, until Jackson and Lee had rekindled southern hopes. Davis was determined to make history repeat itself. Lee had turned the war around by attacking McClellan; Davis instructed Bragg to try the same strategy against Rosecrans. To aid that effort, two divisions had already joined Bragg from Joseph Johnston's idle army in Mississippi. This brought Bragg's numbers almost equal to Rosecrans's. In view of the low morale in the Army of Tennessee, though, Davis knew this was not enough. Having once before called on Lee to command at the point of greatest crisis, the president tried to do so again. But Lee demurred at Davis's request that he go south in person to take over Bragg's augmented army. The Virginian also objected at first to Longstreet's renewed proposal to reinforce Bragg with his corps. Instead, Lee wanted to take the offensive against Meade on the Rappahannock, where the Army of Northern Virginia and the Army of the Potomac had been shadow-boxing warily since Gettysburg. But this time Davis overruled Lee and ordered Long-street to Georgia with two of his divisions (the third, Pickett's, had not yet recovered from Gettysburg). The first of Longstreet's 12,000 veterans entrained on September 9. Because of Burnside's occupation of east Tennessee, the direct route of 550 miles was closed off. Instead, the soldiers had to make a roundabout 900-mile excursion through both Carolinas and Georgia over eight or ten different lines. Only half of Longstreet's men got to Chickamauga Creek in time for the ensuing battle—but they helped win a stunning victory over Longstreet's old West Point roommate Rosecrans.

With help on the way, Bragg went over to the offensive. To lure Rosecrans's three separated columns through the mountains where he could pounce on them individually in the valley south of Chattanooga, Bragg sent sham deserters into Union lines bearing tales of Confederate retreat. Rosecrans took the bait and pushed forward too eagerly. But Bragg's subordinates failed to spring the traps. Three times from September 10 to 13 Bragg ordered attacks by two or more divisions against outnumbered and isolated fragments of the enemy. But each time the general assigned to make the attack, considering his orders discretionary, found reasons for not doing so. Warned by these maneuvers, Rosecrans

7

. Jones, War

Clerk's Diary

(Swiggett), II, 43; Wiley,

Johnny Reb

, 131; Rowland, Davis, V, 548, 554.

concentrated his army in the valley of West Chickamauga Creek during the third week of September.

Angered by the intractability of his generals—who in turn distrusted his judgment—Bragg nevertheless devised a new plan to turn Rose-crans's left, cut him off from Chattanooga, and drive him southward up a dead-end valley. With the arrival on September 18 of the first of Longstreet's troops under the fighting Texan John Bell Hood with his arm in a sling from a Gettysburg wound, Bragg was assured of numerical superiority. If he had been able to launch his attack that day, he might have succeeded in rolling up Rosecrans's flank, for only one Union corps stood in his way. But Yankee cavalry with repeating carbines blunted the rebels' sluggish advance. That night Virginia-born George Thomas's large Union corps made a forced march to strengthen the Union left. Soon after dawn on September 19, enemy patrols bumped into each other just west of Chickamauga Creek, setting off what became the bloodiest battle in the western theater.

Bragg persisted in trying to turn the Union left. All through the day the rebels made savage division-size attacks mostly against Thomas's corps through woods and undergrowth so thick that units could not see or cooperate with each other. Rosecrans fed reinforcements to Thomas who held the enemy to minimal gains, at harsh cost to both sides. That evening Longstreet arrived personally with two more of his brigades. Bragg organized his army into two wings, gave Longstreet command of the left and Leonidas Polk of the right, and ordered them to make an echelon attack next morning from right to left. Polk's assault started several hours late—a failing that had become a habit—and made little headway against Thomas's stubborn defenders fighting behind breastworks they had built overnight. Exasperated, Bragg canceled the echelon order of attack and told Longstreet to go forward with everything he had. At 11:30 a.m. Longstreet complied, and charged into one of the greatest pieces of luck in the war.

Over on the Union side, Rosecrans had been shifting reinforcements to his hard-pressed left. During this confusing process a staff officer, failing to see a blue division concealed in the woods on the right, reported a quarter-mile gap in the line at that point. To fill this supposedly dangerous hole, Rosecrans ordered another division to move over, thus creating a real gap in an effort to remedy a nonexistent one. Into this breach unwittingly marched Longstreet's veterans from the Army of Northern Virginia, catching the Yankees on either side in the flank and spreading a growing panic. More gray soldiers poured into the break,

rolling up Rosecrans's right and sending one-third of the blue army—along with four division commanders, two corps commanders, and a traumatized Rosecrans whose headquarters had been overrun—streaming northward toward Chattanooga eight miles away. Here were the makings of the decisive victory that had eluded western Confederate armies for more than two years.

Recognizing the opportunity, Longstreet sent in his reserves and called on Bragg for reinforcements. But the commander said he could not spare a man from his fought-out right, so a disgusted Longstreet had to make the final push with what he had. By this time, however, the Federals had formed a new line along a ridge at right angles to their old one. George Thomas took charge of what was left of the army and organized it for a last-ditch stand. For his leadership this day he won fame as the Rock of Chickamauga. Thomas got timely help from another northern battle hero, Gordon Granger, commander of the Union reserve division posted several miles to the rear. On his own initiative Granger marched toward the sound of the guns and arrived just in time for his men to help stem Longstreet's repeated onslaughts. As the sun went down, Thomas finally disengaged his exhausted troops for a nighttime retreat to Chattanooga. There the two parts of the army—those who had fled and those who had stood—were reunited to face an experience unique for Union forces, the defense of a besieged city.

Longstreet and Forrest wanted to push on next morning to complete the destruction of Rosecrans's army before it could reorganize behind the Chattanooga fortifications. But Bragg was more appalled by the wastage of his own army than impressed by the magnitude of its victory. In two days he had lost 20,000 killed, wounded, and missing—more than 30 percent of his effectives. Ten Confederate generals had been killed or wounded, including Hood who narrowly survived amputation of a leg. Although the rebels had made a rich haul in captured guns and equipment, Bragg's immediate concern was the ghastly spectacle of dead and wounded lying thick on the ground. Half of his artillery horses had also been killed. Thus he refused to heed the pleas of his lieutenants for a rapid pursuit—a refusal that laid the groundwork for bitter recriminations that swelled into an uproar during the coming weeks. "What does he fight battles for?" asked an angry Forrest, and soon many others in the South were asking the same question. The tactical triumph at Chickamauga seemed barren of strategic results so long as the enemy held Chattanooga.

8

8

. Quotation from Robert Selph Henry,

"First with the Most" Forrest

(Indianapolis, 1944), 193. Union casualties at Chickamauga were about 16,000. Glen Tucker,

Chickamauga: Bloody Battle in the West

(Indianapolis, 1961), 388–89.

Bragg hoped to starve the Yankees out. By mid-October he seemed likely to succeed. The Confederates planted artillery on the commanding height of Lookout Mountain south of Chattanooga, infantry along Missionary Ridge to the east, and infantry on river roads to the west. This enabled them to interdict all of Rosecrans's supply routes into the city except a tortuous wagon road over the forbidding Cumberlands to the north. Mules consumed almost as much forage as they could haul over these heights, while rebel cavalry raids picked off hundreds of wagons. Union horses starved to death in Chattanooga while men were reduced to half rations or less.

Rosecrans seemed unequal to the crisis. The disaster at Chickamauga and the shame of having fled the field while Thomas stayed and fought unnerved him. Lincoln considered Rosecrans "confused and stunned like a duck hit on the head."

9

The Army of the Cumberland clearly needed help. Even before Chickamauga, Halleck had ordered Sherman to bring four divisions from Vicksburg to Chattanooga, rebuilding the railroad as he went. But the latter task would take weeks. So, on September 23, Stanton pressed a reluctant Lincoln to transfer the under-strength 11th and 12th Corps by rail from the Army of the Potomac to Rosecrans. This would handicap Meade's operations on the Rappahannock, protested the president. Meade could not be prodded into an offensive anyhow, replied Stanton, so these corps should be put to work where they could do some good. Lincoln finally consented, and activated Joe Hooker to command the expeditionary force. Stanton summoned railroad presidents to his office. Orders flew around the country; dozens of trains were assembled; and forty hours after the decision, the first troops rolled out of Culpeper for a 1,233-mile trip through Union-held territory over the Appalachians and across the unbridged Ohio River twice. Eleven days later more than 20,000 men had arrived at the railhead near Chattanooga with their artillery, horses, and equipment. It was an extraordinary feat of logistics—the longest and fastest movement of such a large body of troops before the twentieth century.

10