Battleship Bismarck (20 page)

Read Battleship Bismarck Online

Authors: Burkard Baron Von Mullenheim-Rechberg

Around 1600

*

on 20 May, we were escorted through our own minefields by the 5th Minesweeping Flotilla, which was under the command of Korvettenkapitän Rudolf Lell. When we arrived at our rendezvous with the flotilla, we were dismayed to find a number of merchant ships waiting to take advantage of the cleared channel. Their presence was liable to endanger the security of Exercise Rhine and, therefore, was extremely unwelcome. However, it gave the Swedish observers and their British friends the impression that our task force and the merchantmen were operating together. As has been said, they so stated in their reports. Consequently, in London the Admiralty put a lot of effort into puzzling over what the Germans could be intending to do with such a combination of ships and how they might counter whatever it was.

When we left the minefield, the minesweepers were detached and the

Bismarck

and

Prinz Eugen

, still escorted by destroyers, steered a zigzag course at 17 knots to avoid submarines. The south coast of Norway came into view during a magnificent summer sunset. The outlines of the beautiful, austere landscape, with the black silhouettes of its mountains raised against the red glow of the sky, enabled me to forget for a moment all about the war.

Following the line of the coast, we turned westward. We would resume our northerly course after we had rounded the southwestern tip of Norway. Between 2100 and 2200 we passed through the southernmost channel in the Kristiansand minefield, then proceeded at a speed of 27 knots. At all times half the guns were manned.

I was off duty that evening and went to see the film that was showing in the wardroom,

Play in the Summer Wind.

We carried enough films to keep us entertained for the several months we were to be at sea but, after that evening, Exercise Rhine kept us so busy that we were never able to put on another program.

Little did we know, as we watched the only movie shown on the

Bismarck

during the operation, that, on the coast near Kristiansand, Viggo Axelsen, a member of the Norwegian underground, was watching our formation and that another Norwegian actually photographed it! Through his binoculars Axelsen observed our passage, noted: “20.30, a battleship, probably German, westerly course,” and gave this report to his friend Odd Starheim who from a nearby hideout immediately radioed a coded report to London.

*

There it reached the desk of Colonel J. S. Wilson, Chief of the British Intelligence Service for Scandinavia, to whom all reports from the Norwegian underground were routed. He relayed it to the British Admiralty, where it provided confirmation of Denham’s message.

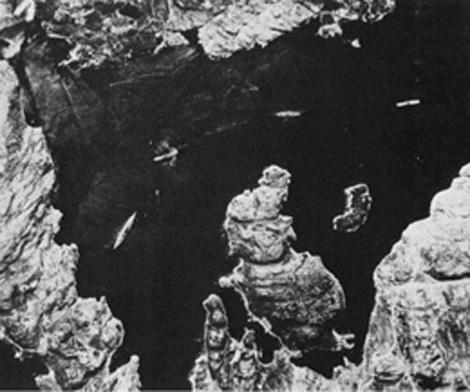

Around thirty minutes after being discovered by Axelsen our task force was sighted by another member of the Norwegian underground, Edvard K. Barth, who was researching bird’s nesting habits on Heröya Island, ten nautical miles southeast of Kristiansand. He saw our task force pass through a corridor in the mine field, turn on a westerly course, and proceed on at a slow speed of around ten knots. Using a telephoto lens, shortly before sunset he snapped the surprising picture that presented itself to him: the

Bismarck

, and

Prinz Eugen

, and two destroyers (the third remained just outside the camera field)—and through such a coincidence made the last photograph of the task force taken from shore.

Some of the

Bismarck

complement relax. (Photograph from Bundesarchiv, Koblenz).

Early the next morning the

Bismarck

went to general quarters. From then on, we would have to be on guard against British submarines, especially during the hours of twilight. Shortly after 0700 four aircraft came into view—mere specks against the sun. Were they British or our own? So quickly did they vanish that we wondered if we had imagined them. It was impossible to say, and the supposed sighting was soon crowded out of our minds by other events.

Not long thereafter, we reached the rocky cliffs near Bergen and before noon ran past barren, mountainous countryside and picturesque, wooden houses to enter Korsfjord under a brilliant sun. The

Bismarck

went into Grimstadfjord, south of Bergen, and anchored at the entrance to Fjörangerfjord, about 500 meters from shore. The

Prinz Eugen

and the destroyers went farther north, to Kalvanes Bay, where they took on fuel from a tanker. With the thought that, in the hazy visibility of these northern waters, our black-and-white stripes might stand out and betray us, both we and the

Prinz Eugen

painted over our camouflage with the standard “outboard gray” of German warships.

The efforts of the German Seekriegsleitung to have the task force break out without being observed suffered a setback. The ships

Bismarck

and

Prinz Eugen

leading, with two of the three destroyers behind, are observed, reported—and photographed!—by members of the Norwegian underground. This unique photograph originates from the ornithologist (later professor) Edvard K. Barth, who was conducting research on sea gulls on the island of Heröya, southwest of Kristiansand. As a member of a secret resistance group and in possession of a camera, nothing seemed to him more natural than to photograph the German task force during its advance. (Photograph courtesy of Edvard K. Barth.)

Apart from that activity, we simply waited for the day to pass. The sun shone continuously and many members of the German occupation forces in Norway, understandably eager to see the new

Bismarck

, came out to visit us. One episode gave everyone who witnessed it a hearty laugh. A soldier, who apparently had run out of tobacco and assumed that we would have a great store of it, got a boat and Came out to the

Bismarck.

As his cockleshell bobbed up and down beside the giant battleship, our men lowered down to him on strings so many cigarettes and so much tobacco that, unless he shared his booty with his comrades, he had enough to smoke for a year!

We were quite close inshore and could feast our eyes on terra firma, from which many Norwegians stared at us. Through our range finders, we could see them having breakfast in their little cottages on the mountainsides. I couldn’t help wondering how many of them were looking with something more than idle curiosity. “Frightful, when you think in a week everyone sunning here on board today could be dead!”—Maschinengast Statz heard that said by someone whom he did not know and was already turning to go. A fateful week later he saw him again in British captivity, and learned that it was Maschinengefreiter Budich who had spoken these words.

Two Messerschmitt-109 fighters flew cover over the

Bismarck

all day, and I can still remember the feeling of security they gave us. A little after 1300 the antiaircraft watch sounded the alarm, but the

Bismarck

was not attacked and our guns did not go into action. The British plane that may have caused this alarm had an objective other than an attack. At 1315 Flying Officer Michael Suckling of RAF Coastal Command, near the end of his reconnaissance mission, was

circling 8,000 meters above us in his Spitfire when he spotted and photographed “two large German warships.” Later that same day, thanks to Flying Officer Suckling, the British were able to identify a

Bismarck-class

battleship and an

Admiral Hipper-class

cruiser

*

in the vicinity of Bergen—thanks were also due to Roscher Lund, as is shown in Captain Denham’s congratulatory letter to him of 23 May. And we, in our ignorance, were just happy that nothing came of the alarm. I did not learn of Suckling’s success until the summer of 1943, when I was a prisoner of war in Bowmanville, Ontario, Canada. One morning I picked up the paper to which I subscribed,

The Globe and Mail

, and there on the front page was an enlargement of Suckling’s photograph of the

Bismarck

at anchor in Grimstadfjord. I have never forgotten my astonishment.

As we lay at anchor the entire day, I was perplexed—this is not hindsight, I remember it very clearly—as to why the

Bismarck

did not make use of what seemed like ample time to refuel, as did the

Prinz Eugen.

Of course, I did not know that the

Bismarck’s

operation orders did not call for her to refuel on 21 May, but I did know that we had not been able to take on our full load in Gotenhafen, and I thought it was imperative to replenish whenever possible, so as it put to sea on an operation of indeterminate duration with a full supply of fuel. The operations order even foresaw that the

Prinz Eugen

, which had a smaller operational radius, might take on fuel from the

Bismarck

while underway!

†

This photograph of the

Bismarck

in Grimstadfjord, taken by Flying Officer Michael Suckling of RAF Coastal Command, confirmed the British Admiralty’s suspicions that German heavy ships were preparing to break out into the Atlantic. (Photograph from the Imperial War Museum, London.)

At 1930 the

Bismarck

weighed another and headed north to join the

Prinz Eugen

and the destroyers outside Kalvanes Bay. The formation then continued on its way. As we slid past the rocky promontories at moderate speed, I was in a small group of the younger officers on the quarterdeck. We wanted to enjoy the Norwegian scenery at close range before we put out into the Atlantic. While we were standing there, the chief of the fleet staff’s B-Dienst team, Korvettenkapitän Kurt-Werner Reichard, passed by, a piece of paper in his hand. Eager for news from his interesting duty station, we asked him what he had and he readily told us. It was a secret radio message from B-Dienst headquarters in German, according to which early that morning a British radio transmission had instructed the Royal Air Force to be on

the lookout for two German battleships and three destroyers that had been reported proceeding on a northerly course. Reichard said that he was taking the message straight to Lütjens. I must admit that we found this news somewhat of a damper because we junior officers had no idea that the British were aware of Exercise Rhine. Now we felt that we had been “discovered,” and that was something of a shock. Surely, I immediately began to theorize, Lütjens would now change his plans. For instance, he might go into the Greenland Sea and stay there long enough for the British to relax the intensity of their search. The whole business of making an “undetected” breakthrough pressed into my thoughts and once again I reviewed what seemed to me to be the breaches of security to which we had been subjected since leaving Gotenhafen: casting off from the wharf at Gotenhafen to the strains of “Muss i denn”; our passage through the—despite its name—narrow Great Belt; the swarms of Danish and Swedish fishing boats in the Kattegat; being in plain view from the coast of Sweden; the Swedish aircraft-carrying cruiser

Gotland

; passing so close to the Norwegian coast near Kristiansand; the sunny, clear day at anchor in Grimstadfjord, with the soldiers coming and going. How could Exercise Rhine really have been kept secret? Might it not have been better to enter the North Sea by way of Kiel Canal and rendezvous with the

Weissenburg

when the timing was best, without touching at Norway? There would have been a risk of detection on this route, too, but probably much less than in our day-long cruise through the narrows of the Kattegat and Skagerrak. But what good did it do to speculate now? In any event, we did not let Reichard’s news get us down and decided to keep our knowledge to ourselves. Passing it on to our men would not have helped anyone.

*