Battleship Bismarck (33 page)

Read Battleship Bismarck Online

Authors: Burkard Baron Von Mullenheim-Rechberg

In the course of the day Lütjens received two personal messages from home. One was from Raeder: “Hearty congratulations on your birthday. After the last great feat of arms, may more such successes be granted to you in your new year. Commander in Chief of the Navy.” The other, dry and aloof, came from the “Führer.” “Best wishes on your birthday. Adolf Hitler.”

During my off-duty time that afternoon I went up to the bridge to have a chat about what was going on with whomever I could. I also hoped to find out some details of the situation, which Lütjens had only outlined in general terms. The officer of the watch was Kapitänleutnant Karl Mihatsch, the Division 7 officer. Even today I can see us standing side by side on the starboard side of the bridge, our mighty ship running through a following sea with the wind from astern.

Mihatsch knew no more than I did, so we could talk only in general terms. We both thought that in spite of the enemy’s intensified efforts to intercept us, we had a good chance of reaching St. Nazaire. We reckoned that the lead we had over the main British force plus the fact that we could still do 28 knots gave us a better than fifty-fifty chance. We were fully aware that, besides the pursuers coming up astern and Force H to be expected ahead, other ships, if not formations, would be approaching from other directions. It all depended on which ships they were and how fast, where they were at the moment, and what radius of operations they had left. Only one thing could not be allowed to happen under any circumstances: the

Bismarck

must not lose speed or maneuverability. If that were to happen, the slow but heavily armed British ships presently astern would be able to close and concentrate more fire power on us than we would be able to withstand. Of course, the most serious threat was an air attack, such as we had experienced from the

Victorious

the evening before. But

was there an aircraft carrier close enough to launch an attack? That was the really big question. We decided, rather lightheartedly, that we had little to fear from other quarters: we regarded submarines, which in any case we were not likely to meet until we got near the French coast, as a secondary danger that did not seriously enter our calculations. And so ended our little “council of war.” It did not produce anything sensational, but it was good to talk to someone, and we parted with contented optimism.

Late in the morning the word went round the ship like a streak of lightning: Contact has been broken! Broken after thirty-one long, uninterrupted hours! It was the best possible news, a real boost to confidence and morale. Exactly how this blessing had come about and where the British ships were at the moment, we did not know. Other things we did not know were that around 0400 Tovey’s task force had intersected our course 100 nautical miles ahead of us and two hours later the

Victorious

and four cruisers had done the same behind us; and, since 0800 we had been standing to the east, away not only from both those formations, but also from the cruisers

Suffolk

and

Norfolk

, which were looking for us to the west. We probably would not even have wanted to know that much detail. Content with the momentary respite, we kept expressing to one another the hope that we would not catch sight of the enemy again before we got to St. Nazaire.

As the time since Lütjens’s address increased and the long day passed into night, the thoughts of those who were not up to date on the enemy situation came to be dominated by the idea that contact had been broken and there was only an extremely small chance that it would be reestablished. The very pleasant contrast between the sound of the guns on Saturday and the calm of Sunday contributed to this feeling. So, too, did human nature, which allows pessimism to fade fast and offers us the welcome support of hope.

What significance did 25 May have for the continuation of Exercise Rhine? No exciting actions took place and by nightfall we had not seen a single enemy either on the sea or in the air, nor did we throughout the night of 25–26 May. But, it could hardly have been a more fateful day.

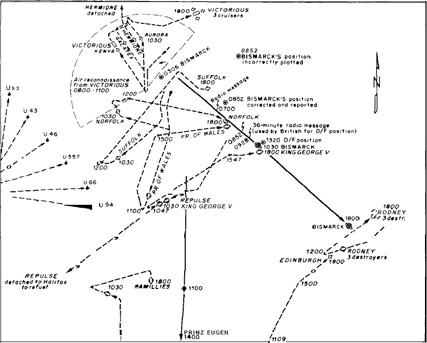

In the morning the enemy lost contact with us—Lütjens didn’t realize it and sent two radio messages—Group West informed him of its impression that contact had been broken—Lütjens accepted this finding and instituted radio silence—the enemy took a bearing on the two messages he did send, but, their coordinates having been incorrectly

evaluated in the

King George V

, our pursuers turned in the wrong direction—Tovey’s loss of time and space was our gain—in the afternoon Tovey returned to the correct course—the British net drew together again—preparations were made for an air search for the

Bismarck

at her supposed position—our prospects of reaching St. Nazaire rose in the morning and sank in the afternoon, but were still real at the end of the day.

*

This reconstruction is based on statements made by survivors landed in France by the

U-74

and the weather ship

Sachsenwald

during their debriefing by Group West in Paris at the beginning of June 1941.

†

Here the survivors’ memories must have played them false. Lütjens can hardly have said anything about being ordered to proceed to a French port. It was his own decision to head for St. Nazaire.

|

On the afternoon of 25 May, we devised a small stratagem whose purpose was to make our adversaries, when next we met them, mistake us for a British battleship.

King George

V-class ships had two stacks, so orders were given to build a second stack for us.

Even with such a change, our silhouette would, of course, give us away to an expert observer on the surface. But we expected that the next enemy to spot us would be in the air. From there it is not easy to recognize ship types, and a second stack could cause real confusion. If it did nothing else, our camouflage would cost the enemy recognition time, especially if visibility worsened, and time became increasingly valuable as our fuel supply became increasingly precarious. So small a thing as delaying our being recognized would be a gain because, once we were recognized, we might be forced, in self-defense, to steam at high speed or to steer an evasive course, either of which measures would strain our fuel supply. Everything, literally everything, counted—and not the least was the fact that the longer it took Tovey’s ships to find the right course, the better was the chance that one or another of them would run low on fuel and have to give up.

Our dummy stack seemed to me to be a feeble trick because, for one thing, unless our ship’s command knew what visual recognition signals the British exchanged when they met, it would not be effective. Perhaps they did know them. I cannot say. Not only that, but British battleships operating on the high seas were usually escorted by destroyers, and the

Bismarck

had no screen, which would certainly

make any enemy scout think twice. However, a feeble trick was better than none at all.

Lütjens must have bitterly regretted not having taken the opportunity to fuel in Grimstadfjord or from the

Weissenburg

after we got under way. Ever since it had been determined that part of our fuel supply was inaccessible, more than twenty hours earlier, the

Bismarck

had had to proceed at an economical 20 knots. Had we been making the 28 knots of which her engines were capable, we would have been 160 nautical miles nearer to St. Nazaire and under cover of the Luftwaffe. We would not have had to worry about camouflaging ourselves, either.

With sheet metal and canvas, we built a dummy stack and painted it gray to match the real stack. It was to be set up on the flight deck forward of the hangar. Men from the workshops went at this unaccustomed task with enthusiasm until darkness fell; for them, it was a welcome change from the routine of long war watches.

Our chief engineering officer, Korvettenkapitän (Ingenieurwesen) Walter Lehmann, who took a personal interest in the dummy stack, naturally wanted to see for himself how his men were going about their task. From the first, he had established a close and confidential relationship with them. It was reinforced by the bull sessions he held, preferably near turret Dora, whenever anyone did something wrong. He would take the culprit aside and, to put him at his ease, growl, “No formalities!” As a survivor put it, “You had to walk round the turret with him and could say whatever was on your mind.” In Gotenhafen, while liberty was canceled in preparation for our departure, a young stoker learned that his mother was dying. He was heartbroken. A sympathetic comrade took him to Lehmann. The boy blurted out, “Please, Papa,” then, overcome by emotion, fell silent. “Now tell Papa,” Lehmann said, “it doesn’t matter, what’s got you down?” Before long, all his men were calling him “Papa Lehmann.”

So Papa Lehmann came and took a look at what was going on with the stack. “We really must,” he said, “fix it so that it will smoke as it should.” The ship’s command took up his jesting idea, and word was passed over the loudspeakers, “Off-duty watch report to the First Officer’s cabin to draw cigars to smoke in our second stack!” The hilarity that this order caused did a lot to raise morale.

When the dummy stack had been completed it was left lying on the deck. It was not to be rigged until the order was given. In the meanwhile, I helped to compose several English-language Morse signals for use in the event of an enemy contact.

Korvettenkapitän Walter Lehmann, chief engineer of the

Bismarck.

(Photograph courtesy of Frau Ursula Trüdinger.)

Lehmann’s big worry that day was not so much the fuel shortage created by the oil in the forecastle being cut off, as it was the danger of saltwater getting into the boilers. As a result of the flooding in port No. 2 boiler room, the feedwater system of turbo-generator No. 4 had salted up and the same danger was threatening power plant No. 3. If seawater got into the boiler through the feedwater system, unevaporated water might be carried into the propulsion turbines along with the steam and, in no time at all, destroy the turbine blades and lead to “blade salad.” Therefore the feedwater in all the turbo-generators must be changed immediately. But our high-pressure boilers took so

much feedwater that we had trouble producing enough to keep pace with the demand. An all-out effort to make our four fresh-water condensers and auxiliary boiler produce enough was successful and by the evening of 25 May the danger had passed.

From

0400

to

1800

, German Summer Time, on 25 May. Movements of the opposing forces after the loss of contact and Admiral Lütjens’s two subsequent radio signals. (Diagram courtesy of Jürgen Rohwer.)

In the afternoon we reduced speed to 12 knots to facilitate the repair work still being done in the forecastle. With much difficulty, men in diving gear climbed into the completely flooded forward compartments and opened the oil-tank valves, which gave us a few more hundred tons of fuel.