Below Mercury (14 page)

Halfway down the corridor, Helligan’s expression changed. His walk became hurried. He stumbled, and broke into a run towards the restrooms at the end of the corridor.

He banged the door open, and fell into the nearest stall on his knees. His chest heaved, and he threw up copiously, the hot vomit spewing into the toilet bowl at the thought of what he had done.

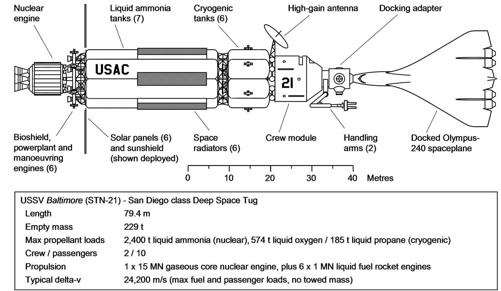

Ten days out from Earth, and the huge mass of the deep space tug

Baltimore

tumbled end-over-end through the empty wilderness of space between Earth and the Sun.

The Earth was eight million kilometres away, still visible as a bright, blue jewel against the backdrop of stars, while the tug fell away sunwards in a long ellipse towards its appointment with Mercury.

The

Baltimore

and its brethren were the biggest spacecraft in the Astronautics Corps, and they existed for one purpose: to transport crew and materials round the Solar System. Boosted into space in sections by huge launch vehicles, and assembled and fuelled in Earth orbit, the

Baltimore

could never land on any planet. It lived out its entire life in space, plying back and forth between orbits around planets and moons, hauling cargo modules, or ferrying crews to and from the manned bases. The tug could undertake even longer voyages entirely on automatic pilot, disappearing into the vastness of deep space and returning with thousands of tonnes of liquid propellants from the refineries on the frozen outer moons of Jupiter.

The

Baltimore

was enormous, stretching eighty metres from the exhaust nozzles of its giant nuclear engine to the docking adapter at the far end. As it fell through space, it rotated about its centre of mass at a leisurely three revolutions a minute, imparting a small apparent gravity to the manned parts of its structure.

At the aft end of the tug was the large and heavy mass of the nuclear engine and power plant. Around it, swathed in reflective insulation, an intricate network of propellant and cooling lines ran between the engine and the generators that provided electrical power for the tug.

Behind the engine and its heavy neutron shield were six huge solar panels for backup power, each over seven metres long. Arranged in a circle round the reactor mount like the petals of a giant flower, the solar panels supported a vast, circular sunshade of shimmering, reflective plastic. As the

Baltimore

rotated, the shadow of the sunshade raced out and over the long length of the tug, plunging it into darkness, and retreated again, in an endless cycle, as regular as a clock.

In the final stages of the voyage, the tug’s rotation would be halted and the sunshade oriented permanently against the Sun, to provide continuous shadow for the tug’s structure. For now, though, the heating loads were low enough to allow the tug to rotate and create its illusion of gravity.

Behind the sunshade, a cluster of seven giant cylindrical tanks, each one over thirty metres long, formed the middle section of the tug, and held the liquid ammonia propellant for the tug’s nuclear engine.

Forward of the main propellant tanks, six smaller, heavily insulated tanks held the tug’s reserves of cryogenic fuels; hundreds of tonnes of liquid oxygen and propane for refuelling the manned vehicles that it towed through space.

At the forward end of the tug, in front of the cryogenic tanks, was the crew module, providing two decks of living accommodation for the flight crew and passengers. Finally, locked firmly in place to the docking adapter at the end of the crew module, the spaceplane waited, its systems shut down until the tug reached Mercury.

Matt Crawford stood by a porthole on the lounge deck, gazing at the stars wheeling past outside. He had found he needed to look outside at least once a day, just to affirm that there

was

an outside beyond the walls of the crew module, and to see the cold hardness of the stars in the jet-black sky.

Staring at the scene for too long could induce motion sickness, though. Matt released the polarisation controls, and the view faded to black. He turned and walked over to the semi-circular couch in the centre of the lounge area. Weight bands on his wrists and ankles helped him to move normally in the low gravity, but he was careful not to hurry. The gentle acceleration produced by the tug’s regular rotation was only one-third that of Earth’s gravity, but sudden movements could still confuse the vestibular system.

The circular room of the deck was deserted. Elliott and Wilson were asleep, the curtains drawn over their bunk areas. Clare was on duty on the command deck one floor below, and Abrams and Bergman were down there as well; Matt could hear their voices coming up through the ladder stairwell. At first, it had seemed odd that the forward end of the tug was ‘downwards’, but Matt had quickly got used to this apparent contradiction.

The hourly news was playing on the link from Earth, but Matt had already watched it over breakfast. The small dishwasher swished and hummed in the background. It was easy to believe that he was in an apartment room on Earth, Matt thought, and not in deep space, eight million kilometres from home.

Matt cast an eye round the nine-metre diameter circular lounge deck, to check that he had put everything back in its place before his watch started. Spacecraft became cluttered very quickly, with so many people living together in a small space. It was more than just courtesy to leave the rest area tidy for others; it was a necessity.

The lounge deck was devoted entirely to the needs of the passengers, and the flight crew when they were off-duty. It housed eight individual sleeping berths arranged round the circular walls of the deck, each with curtains to create a private space. A bathroom housed the twin luxuries of a decent shower and a zero gravity toilet, and the rest of the deck held the kitchen facilities and a lounge area, for relaxing, reading, or watching movies. These home comforts would have seemed extravagant to the early space explorers, but for long voyages through the depths of space, they were essential for crew morale and well-being.

In the centre of the deck was a circular opening with a narrow handrail, through which a vertical ladder ran, giving access to the command deck below. The ladder also led upwards into a conical chamber that contained food stores and other consumables.

Above this, a heavy door opened into a narrower cylindrical section, five metres long, nestling in the space between the six cryogenic fuel tanks.

Surrounded on all sides by thick, polyethylene radiation shields, and by the heavy mass of the liquid propellants in the fuel tanks, this was the innermost refuge for the crew in the event of a major solar radiation event.

It was also where the twelve stasis chambers were located, for use on the long voyages to Mars and the outer planets. Spaced out around the walls of the refuge, each unit could maintain a healthy human being in a state of reduced metabolism for many months at a time, saving huge amounts of food and other consumables, and reducing the journey time to the blink of an eye.

For the relatively short flights to Venus and Mercury, however, the stasis chambers were rarely used, and the coffin-like chambers, with their attendant medical consoles, were silent and dark. The effect was uncomfortably reminiscent of a tomb, and although the refuge could be used for additional sleeping space if needed, most crews tended to leave it alone.

It was nearly time for Matt and Abrams to take over the night watch, and Matt climbed down the ladder into the command deck. It was noisier here; the hum of equipment and subdued sound of radio transmissions from distant bases filled the air.

As well as the tug’s flight controls, the command deck housed communications and environmental equipment, a second bathroom, four further berths, and a small gym area, where Bergman was pedalling away vigorously on the exercise bike.

Matt walked over to the flight deck, to where Clare Foster sat in the commander’s seat, facing the slope of the docking windows. The flight deck seats and control consoles were mounted on struts so that they could be reoriented for weightless flight, when a good view was needed over the tug’s nose. For now, though, the seats faced ‘outwards’. Matt could see Clare’s reflection in the window glass, looking back at him.

‘Morning.’

‘Hi.’ Clare stretched and smiled. ‘You ready to take over?’ Like all of them, she wore the standard dark blue flight overalls, with her name over the left breast pocket. Unlike the passengers, however, she carried the astronaut badge of the Corps over her name, and her rank insignia on the shoulders.

‘Sure. Anything I should know about?’ Matt got into the right-hand seat, and slid it forward to a more comfortable position.

‘Nope. We did a small correction of the rotation axis a few hours ago.’ She pointed at one of the displays. ‘It shouldn’t need any adjustment for a day or so. Looks like you’ve got a quiet watch.’

The door of the bathroom, over by the gym area, opened and Abrams emerged. He sauntered over to the flight deck.

‘Mind if I take first turn?’ Matt asked.

‘Sure, be my guest,’ Abrams said, in his easy drawl, ‘I’ll just watch from here.’

Clare pushed her seat back.

‘Okay guys, I’ll be upstairs if you need me.’ She got up, and disappeared up the ladder to the lounge deck.

Abrams leant on the back of Clare’s vacated seat, watching Matt run through the checklist. Flight regulations required that one crewmember had to be seated at the flight deck at all times, so they took it in turns to keep watch, while the other got on with the rest of their duties.

‘Any icebergs ahead?’ Abrams asked, wryly.

Matt laughed. Sitting there, it was easy to imagine that they were the lookouts on some ocean-going ship, cruising in smooth seas at night. Instead of islands and shoals, however, the navigation display showed landmarks that truly belonged to the Space Age; distant planets, the location of the Sun, and the trajectory of the

Baltimore;

a gentle curve that arced out across the vastness of space.

‘Be back in an hour,’ Abrams said, and left Matt to the watch.

Matt enjoyed being at the flight deck station on the watches; it felt like he was flying the tug, although in reality he could do very little. The autopilot would not allow him to make any changes, or fire any of the thrusters, without disconnecting, and

that

would sound an alert that would have Clare and Wilson down here in seconds.

The checklist for the night watch was simple, and Matt was through most of it in a few minutes. The last item was the routine visual survey of the tug’s exterior, and Matt clicked through the various cameras, positioned at strategic points on the tug’s exterior.

He started at the nuclear engine at the rear of the tug, panning the camera slowly over the cooling fins of the reactor chamber, and the cluster of engine nozzles. This was somewhere that no human could go while the engine was at full power; the radiation from the core was just too dangerous. Now, however, the reactor was just ticking over during the long cruise, its waste heat providing electrical power for the tug’s systems.

Matt shifted to another camera, and started working his way along the length of the vast fuel tanks and space radiators. He took his time, panning the camera over every metre of the tug’s length. The tanks plunged into darkness, then emerged into sunlight again as the

Baltimore

turned over again in its rhythmic cycle.

He moved over the surfaces of the giant tanks and the louvred vents of the space radiators, changing cameras as he went. It was rare to find any problem, but a stray micrometeoroid could sometimes punch a tiny crater into the thin alloy of the tanks, and he inspected the surfaces carefully for any signs of damage.

He changed camera again to examine the forward end of the tug. With its separate fuel tanks, crew module and docking adapter, this part of the tug was effectively an independent spacecraft. In an emergency, it could separate and blast away from the rest of the tug using its own small rocket engines, hidden away within the attachment truss. Once separated, the forward section could function as a ‘lifeboat’ for the crew until rescue came, and could even perform limited orbital manoeuvres under its own power.

Below the crew module were two heavy-duty handling arms, each with a powerful, vice-like hand that could be used to manipulate cargo loads. One arm was retracted and hung at rest, the other held the drop tank that the spaceplane would need for the descent to the surface.