Below Mercury (18 page)

Mining in area:

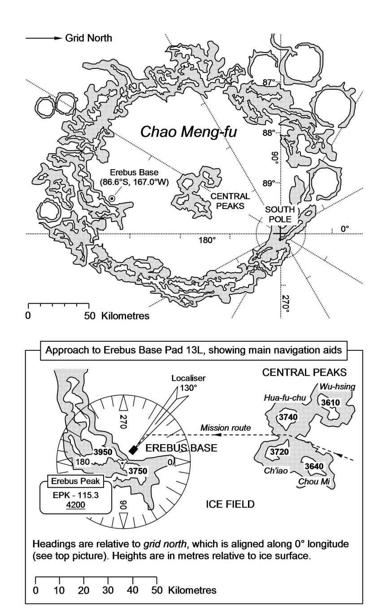

Erebus Mine, 86.6°S, 167.0°W, operated by Planetary Mining Inc. Mining for helium-3 and liquid fuels in ice deposits on crater floor, also deep mining of precious metal deposits (gold and platinum group metals) under crater floor. Extraction, processing and refining facilities for LO2, LH2, mixed alkanes, ammonia and water. Refuelling and resupply base. Space tug orbital refuelling base.

Excerpt from

Engineering Geology of Mercury

(USAC Geological Survey, 2nd edn, 2129).

Matt watched from his seat in the spaceplane as the enormous structure of the

Baltimore

dwindled upwards into the sky over Mercury. They had left the tug in the care of its autopilot, and the huge silver flower of the sunshield rippled in the backwash from the thrusters, as the tug moved round to face away from the Sun once more.

The spaceplane was falling away from the tug; Clare had fired the engines briefly to change their circular orbit to a long ellipse that would come within a few kilometres of the surface. Once they were close to the South Pole, she would fire the engines again in the main burn to brake their orbital speed and bring them in for a landing.

There wasn’t much to see during the long minutes as the spaceplane fell backwards towards Mercury. The view out of the spaceplane’s forward windows was obscured by the large drop tank, latched onto the nose that supplemented the spaceplane’s own tanks with extra fuel for the descent.

Instead, Matt watched their trajectory on the navigation display, and the small icon of the spaceplane as it followed the long curving line downwards.

The mission team were wearing the same crew escape suits and spacesuit helmets that they had worn on the ascent through Earth’s atmosphere; their faceplates were raised for now, but would need to be lowered for landing.

‘Tanks are at full pressure,’ Wilson reported, ‘ready for de-orbit burn.’

‘Arm ignition.’

This time, there was none of the drama of the orbital climb; here in space, the spaceplane coasted in serene silence as Clare and Wilson prepared for the main de-orbit burn.

‘Main engine ignition in ten.’

Matt heard the turbopumps spin up, but the sound of the main engines firing was quieter than it had been on the orbital climb, with just a muffled roaring to accompany the shove in the back from the four rocket engines firing. To Matt’s relief, it was a gentler shove than it had been back on Earth; the spaceplane’s mass was considerably greater due to the extra fuel.

In a little over four minutes, it was over; the drop tank was empty and the main tanks were down to two-thirds full. The roar of the engines shut down, hissing into silence. The spaceplane had lost most of its orbital velocity, and was on its way down to the surface on a long curve that ended at their target.

‘Tank jettison,’ Clare ordered. Wilson lifted a safety cover and thumbed a switch, and there was a hollow bang as the empty drop tank detached from the spaceplane and fell away, tumbling as it went. The spaceplane’s nose section raised, closing over the docking adapter, and locked shut with a thump.

Clare rotated the ship through 180 degrees, until it faced forward on its flight path. Below and slightly ahead of them, the empty tank glinted in the sunlight as it spun down towards the crater-strewn landscape below.

‘Landing jets. Establish descent profile.’

On the underside of the spaceplane’s wings, and beneath its nose, hatches opened wide to reveal the landing jets; three compact arrays of small rocket engines, designed to provide the high level of control needed for a precision landing on a planetary surface.

The jets ignited with a ripple of muffled thuds, and the spaceplane settled into a slightly nose-up attitude as the engines slowed and flattened the descent, setting them up on the glide path towards their target.

From his vantage point behind Clare’s seat, Matt could see the dark holes of countless craters, lit in stark relief by the low Sun on their left. The craters flowed past beneath them, tens of kilometres across, their tumbled rims mingling and overlapping, impact upon impact, monuments to the ancient bombardment of the Inner Solar System.

The cockpit was quiet now except for the humming of the instruments, and the occasional word between Clare and Wilson as they monitored the descent. The only light in the cabin came from the glow of the flight and navigation displays, and the lines of flickering red numerals on the autopilot displays below the window.

The landing jets hissed gently in the vacuum as the spaceplane fell lower. Matt and Bergman sat behind the pilots, not saying a word, craning forwards to watch the surface, far below them. They had memorised the approach from hundreds of photographs and navigation charts, and they watched as the craters rolled by, names of poets, writers and artists from vanished centuries.

Matt, peering out of the left side windows, saw a distinctive crater-within-a-crater, over eighty kilometres in diameter, slide past. He felt a quiver of fear and excitement in his stomach. After a journey of millions of kilometres, they were minutes away from landing.

‘Two hundred kilometres to the crater rim, guys,’ Clare called out, pointing at the navigation display, which showed their progress towards the target. Without the benefit of any landing aids, they were flying entirely by the craft’s inertial navigation systems, checked against the major terrain features. Contour lines and height warnings slid down the screen, tracking the terrain below.

Ahead of the spaceplane, the black pits of the South Pole craters drew closer. Matt watched as the huge craters expanded beneath them, great gulfs of darkness in the landscape below. The clear, beautiful colours of the landscapes in Meng-fu’s tranquil paintings would never be seen here. The only colours were the Sun-blasted whites and greys of the Mercurian landscape, and the perfect, razor-edged blackness of the shadows.

The low Sun, clinging to the horizon on their left, highlighted every fold in the alien landscape, throwing the crater rims and surface features into sharp relief. Immense mountain chains, their peaks rising into the sky, rose in jumbled ranks round enormous craters, huge impacts that had shattered and twisted the landscape. In places, faulted canyons, kilometres deep, ran between overlapping crater rims, emptying into the shattered sides of more even more ancient crater basins, before plunging down into blackness. Great scarps, remnants of faulting from the primordial cooling of the planet, reared out of the ground and fell behind, revealing wrinkled and folded crater plains, blurred and confused by old lava flows.

‘There it is.’ Wilson broke the silence, pointing forwards out of the window. ‘Meng-fu crater, ahead eleven o’clock. And I’ve got a very weak signal from the South Pole DSNB now, must be running somehow. We’re right on course, maintaining grid heading two seven zero. Crossing crater rim in two minutes.’

The four passengers craned to see the crater for the first time.

A vast gulf of darkness, bigger than any crater they had seen, opened ahead and slightly to their left. One hundred and sixty-seven kilometres from rim to rim, it expanded until it spanned the whole horizon ahead. It was so huge it defied the senses; it was like a black hole, a pit of nothingness that dragged the very light down from the stars.

‘Bring us down to ten thousand metres,’ Clare said, and the sound of the landing jets reduced slightly as Wilson set the change into the autopilot.

The curved horizon flattened as the spaceplane sank lower on the hissing landing jets. The world beneath them expanded and spread out, moment by moment. In a slow and irresistible shift of perspective, it changed from a planet below them, into a landscape spread out around them.

The Sun, already low in the black sky, sank towards the horizon as they descended, and the crater shadows widened beneath them. They were in the depths of Bach quadrant on Mercury, where the Sun had no power to warm the frozen mountains. A sudden nightfall was closing around them, and terrors stalked the night below.

Now the landscape twisted itself into new and terrible shapes, range upon range of mountains rising into the sky, the outliers of the crater walls of Chao Meng-fu itself. The mountains slid by, rising ahead of them, higher and higher with each successive ridge as the crater walls approached.

‘I’ll make the turn as soon as we’re over the crater rim,’ Wilson said.

‘Yeah,’ Clare muttered, her eyes scanning the horizon. ‘Better make our final position report, we’ll be losing contact soon,’ she added.

Wilson thumbed the transmit.

‘Deep Space Control, Mercury Two Zero Seven, crossing Meng-fu crater rim on grid heading two seven zero, radar altitude one zero zero, entering radio fade.’

No words were necessary now as the crater rim came towards them. As they passed overhead, the low Sun illuminated the line of mountain peaks in terrible relief, and then the spaceplane passed over, and out into the huge gulf of Chao Meng-fu crater. Below them, the mountain walls fell away again in great faulted terraces, down into the permanent darkness of the crater floor. In the centre of the crater ring, four tall peaks stood illuminated by the Sun, like islands in a black sea, monuments to the titanic impact that had made the crater long ago.

‘Turning left onto two zero five. Eighty kilometres to Hua-fu-chu waypoint.’

Wilson banked the spaceplane into a steep left turn. The horizon tilted in front of them, and then moved back level again as the ship settled out on its new course, heading straight out over the crater floor towards the central peaks and the Sun that grazed the distant crater rim.

‘Set descent to take us through the peaks at three thousand, and watch your clearance,’ Clare ordered, her voice tense. Wilson reached out to the autopilot, and the landing jets fell to a hushed whisper.

The ship seemed to hang above the crater, as if reluctant to fall into the terrible gulf, but Mercury’s gravity would not release it, and pulled it relentlessly inward. Like a winged demon returning to the underworld, the spaceplane slid into the abyss below them, deeper and deeper, until it felt like they were falling into the pits of Hell itself. There was no way of telling how deep it went; it was like falling into a bottomless void.

The voices on the deep space control channel in Wilson’s headset became garbled and broken, came back again briefly, then disappeared into a meaningless hiss of random noise as the ship fell out of radio contact.

The distant peaks of the crater rim retreated towards the edges of the world. The Sun followed the mountains down the sky and set behind them, shrinking to a bright arc on the edge of the world. There was a sudden flicker as the last rays stole between the mountain peaks, then it was gone, and darkness closed around them.

The cockpit windows adjusted to the loss of light, losing their polarisation and protective tint, and stars came out in the great bowl of the sky above the crater. Above the vanished Sun, the solar corona flared, the hidden nimbus of light that was invisible from Earth except during an eclipse. Out here, close to the Sun and with no atmosphere to refract the Sun’s light, the corona was enormous; a huge arch of luminous gas reaching high above the crater rim.

Their descent continued, and they watched as the corona sank behind the mountains. It faded to wisps and filaments of glowing gas, flickering and blowing above the crater rim, a reminder of the deadly radiation that sleeted over the landscape. As they fell deeper still, the last faint remnants sank from sight, leaving the sky to the stars.

Below them, and all around, the utter blackness of the crater seemed to suck them in, a deeper night than the starry sky above. The crater rim marched on the horizon, black against the stars.

Ahead of them now, the central mountains rose into the sky, growing with each minute as the spaceplane slid towards the heart of the crater. The peaks climbed out of the darkness of the crater and into the high sunlight, great spires of rock formed from the rebounding of the ancient impact flow, their tumbled lower slopes hidden in the darkness.

Their course took them through a valley between two of the tallest peaks. As they drew closer, the sunlit heights soared up into the sky on either side until they were lost to view, high above the spaceplane. On the night vision displays, they could see the invisible ramparts and mountain buttresses that slid silently past alongside in the darkness. Great screes and boulder slopes fell down toward the hidden valley floor, the sheer rock faces softened from countless minor impacts.