Big Sex Little Death: A Memoir (33 page)

Read Big Sex Little Death: A Memoir Online

Authors: Susie Bright

because you don’t see the point in bringing this out into the open

because you don’t feel like living anymore

because you didn’t mean it that way

because you’re locked up

because you’re doped up

because what did lesbians ever do for you, anyway

because it hurts to be criticized and cut down

because people are cruel

because you’re not a hero

because

the first cut

thank you

is the deepest

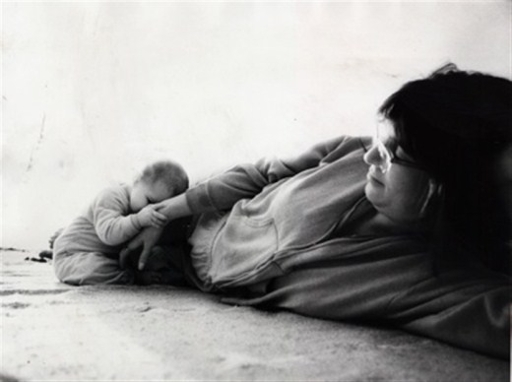

Motherhood

You can house their bodies but not their thoughts.

They have their own thoughts.

You can house their bodies but not their souls,

For their souls live in a place called tomorrow,

Which you can’t visit, not even in your dreams.

— Kahlil Gibran

I

got pregnant in 1989, when I was thirty-two, the same age as my mother when she had me. I was due in early June, which inspired a flood of Gemini good wishes from my

On Our Backs

readers, who were as surprised and curious as everyone else.

“Did you inseminate or did you party?” asked Marika at our Christmas party. I laughed so hard, she said, “Oh! You partied.”

I did party. But I also was falling in love. And then out of it. My bisexual heart was in a bit of torment.

It was the eve of a baby boom — I didn’t know any other women my age who were taking the plunge. They’d all done it a lot earlier, or had foresworn the whole racket — that would’ve included me.

My daughter-to-be, Aretha Elizabeth Bright, surprised me in every way — including her late-June Cancerian arrival. She had eyes like dark moons, and when the midwife put her in my arms, she looked into me like no one has ever looked at me before.

When Aretha was six months old, a neighbor of mine saw us walking home from the grocery store, baby tucked into her stroller, a loaf of bread sticking out between her curly head and the diaper bag.

“Look at you!” he exclaimed, as if a figure of the Madonna and Child had sprung to life. Well, I didn’t mind if he wanted to make a fuss. The oxytocin was flowing through my veins.

This old codger, Mr. Hera, had always taken a dim view of what he knew about me from the newspapers — he’d make a chauvinist what’s-the-world-coming-to? remark whenever we ran into each other on garbage night.

He leaned over to admire Aretha’s little face, then looked up at me with a smile: “Now, isn’t this the very best thing you’ve ever done with your life?”

I covered my eyes with my hands and laughed. “On no, Mr. Hera, please, don’t ruin it.” Then I straightened up and touched his shoulder. I'm a few inches taller than him. “You know, Mr. Hera, you’re right, you’re right — more than you even know.”

My pregnancy and my daughter’s life worked on me like True North. I had to Protect the Baby, but I ended up Protecting Me. My maternal certainty was a tonic. I knew whom I had to defend. Malingerers, fakers, and self-destructive impulses were red-tagged and booted. I had a magnet in me for doing the right thing.

How could someone like me, who got pregnant by accident, unpartnered, uncertain of her future, find motherhood so gifted? Is there really a time to every purpose under heaven?

When I was pregnant and staring at my enormous navel, I wondered if this was my comeuppance. All the time I spent as a child fuming, crying, hiding, swearing I would never put another human being through such cruelties as were visited upon me … Would I now be humbled?

I did get pregnant unexpectedly. I spent the first thirty-one years of my life being either a lesbian or a complete martinet about birth control and all of sudden … I got sloppy. It was out of character. So was my pregnancy test … I burst into tears when I got a (false) negative. “It can’t be true; it can’t be true!” I sobbed in the car next to my friend who drove me home from my doctor’s appointment. She was bewildered at my rage and tears. “But you never wanted to have children!” she said.

That was true. I could convince anyone about zero population growth; I would rant about the narcissism of parental conceits. I’d written articles on why a woman’s worth is not the sum of her womb. I’d write them all over again, too.

But the real reason I couldn’t imagine having a baby was that I was afraid of my temper, afraid of doing those things for which you can’t ever fully apologize. I knew that my mom had been “sorry” that she had hit me (after all, it wasn’t as bad as she’d been hit). She didn’t remember threatening me (after all, we did survive). Maybe it was my fault sometimes; isn’t that what kids think? Mommy, I'm sorry, I’m so sorry. It changed nothing for her. But then, her actions had very little to do with me.

If I stayed pregnant, if I had the baby, I had to take a vow. But a real vow entails keeping your promise … could I keep a pact that had been broken to me, however much in sorrow? Could I say to my daughter, “I will never hit you, I will never lose you. I will never hide the truth from you, I will never try to extinguish you?”

It’s not like anyone “planned” to do differently with me.

My conception appeared madcap to many of my friends. Yet I think I had a lot better idea of what I was getting into than my mom did when she was thirty-two.

I had a soft spot for the man I conceived with, but we knew we weren’t destined for longevity, nor he for any kind of parenting. We talked about it frankly. I tol

d him, “I’ll never ask you for anything, but I know, wherever you are, you’ll be proud of her.” He asked me to take care of

his family belongings before he went on the road again — I knew he trusted me. He was the High Plains Drifter, shimmering into disappearance in the heat.

Rotation

I

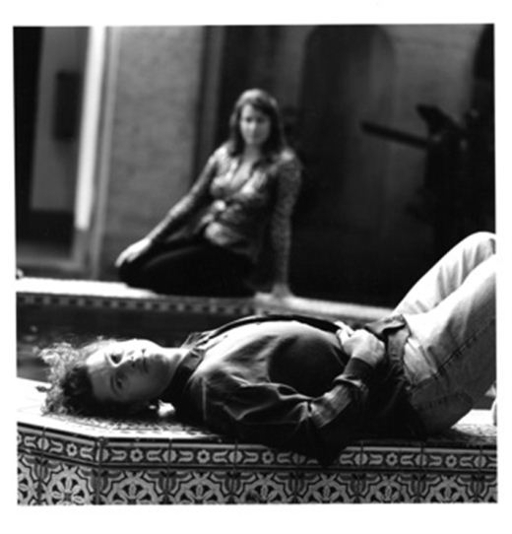

met Jon shortly before I got pregnant; we became lovers and friends and stayed that way for the next twenty-some years.

I met him because my tires needed to be balanced. He will tell you that I arrived at the mechanic’s garage in a black catsuit, like Emma Peel, and that I tried to lure him away to a beach down the coast where everyone strips off their clothes and huddles, making love in driftwood caves that other nudists erected to protect themselves from the wind.

It’s true, I flirted with him; but it was because he was a really good talker, handsome, and completely alone in a run-down tire shop in the Outer Sunset. It was such a sweet escape to have a moment of screwball comedy in the Ocean Beach fog.

He didn’t come away with me the first time. The only remembrance from the tire shop is that we kissed goodbye, my low-profile tires beckoning. I don’t think I’d ever kissed my mechanic before.

He kept my number, which I’d scrawled down on the credit card receipt, and six months after our meeting, he left a message at my office: “Do your tires need rotating?”

My whole life needed rotating.

We both had other lovers, we both had messy breakups, we both had recently ended relationships with “older women” whom we cared for dearly. We also had a talent for putting ourselves in peril by climbing into bed with some scary characters. I remember once when my current shady character and his scary girl sought each other out and took each other to bed. It was two con artists sizing each other up. They wanted to see what the other one was capable of. Maybe they wanted to compare notes on the thrills of fucking Raggedy Ann and Andy. The bandits competed to see who was the most deadly. It was

a draw.

During my thirtieth year I had started seeing a therapist, and even though she barely said a word, there is something about sitting in a room talking to yourself, a kind face across from you nodding at your every word, that is bound to reveal a few things.

I made a joke to her one day, “Well, I have to say, at least my new friend Jon isn’t trying to kill me or himself or anybody else.” He took great care.

Everyone enjoys those qualities in a lover. But at my low ebb, distressed at breaking up with Honey Lee and embarrassed by my leaps into the abyss, Jon was like a hand that unexpectedly reached out to me. It wasn’t a matter of whether I was attracted, or not — I just had to grab it. I grabbed — and my attraction grew exponentially.

Jon has a good story from when he worked as a marine rescue guard in the oceans of the northern California coast. He saved people from drowning, and retrieved corpses from the water. One day, his crew got a message that there was a woman, fully clothed, ranting and raving and dog-paddling out beyond the city wharf. The Fire Department directed one of their swimmers, Logan, to jump in with Jon and swim out to the victim with a raft. Logan approached the woman, his red lifeguard float in front of him, and called out, “Grab onto this.”

The vic yelled back, “Get that away from me; it’s just an extension of your penis!”

The woman was a strong swimmer, albeit intoxicated, and not yet fatigued by the cold. Jon swam a little closer to her. He complimented her great swimming; he suggested that they could swim together, that he’d follow her. He was counting on her not being in condition to last out there too much longer. Her fantastic gender lecture notes grew quieter, less frequent. All three of them started paddling down the surf line; as she tired, they harnessed her with the rescue float.

I think I wore out, too, though perhaps not as gracefully. Pregnancy gave me such a new kind of appetite. I was hungry for someone whose patience preceded him.

My first trimester was biblical. Each promise, made in great sincerity, came to pass. The family members who drew close to me at that time were in love with Aretha from the time she was an unnamed twinkle. Jon, who is her dad in every sense of devotion. Godmother Honey Lee, her second home. Aunt Temma and Tracey. Auntie Shar. My dad, his wife and family. And my mom, too. For an only child without a ring on my finger, I was loved, and Aretha was cherished, in one abundant circle after another.

My mom’s the one who sealed the deal on picking her name. I’d been reading baby name books until my eyes were crossed. I sent Elizabeth a list of a few that I liked, including “Aretha.”

My mother wrote back the next day, with great excitement. “Oh Susie, Aretha is Greek for ‘the very best,’ the most outstanding and virtuous. That is the perfect name for the perfect baby.” She wrote the Greek letters out in cursive.

Neither of my parents knew one thing about R&B, or about most popular music. The day after I got my mother’s message, my father sent me a color travel postcard of the stone ruins of Goddess Aretha’s Grecian temple, which lies in what is now Turkey.

Only Bill and Elizabeth, of all the people in the world, would respond to the name “Aretha” with the enthusiasm of the antiquities.

I knew family ghosts don’t go away. I’ve enjoyed the beneficial ones. But I knew that abuse loves reruns. Penance and exorcisms don’t work. I still needed a plan to keep my promise to be “a good mom,” something stronger than good intentions.

I would probably lose my equilibrium — or come close to it. I confided to Jon, “If I fuck up, I have to tell another adult what happened, right away, and get some help picking up the pieces.”