Read Black Gotham: A Family History of African Americans in Nineteenth-Century New York City Online

Authors: Carla L. Peterson

Black Gotham: A Family History of African Americans in Nineteenth-Century New York City (37 page)

In their accounts, neither Powell nor Maritcha stated whether the rioters were neighbors, strangers, or both. But what is certain is that they were bent on destruction, and the people who lived near these black families—with one exception in each case—found no compelling reason to come to the defense of the victims.

On Friday, July 17, John W. Rode, a sergeant from the fourth precinct station on Oak Street, sent Albro Lyons two notes, carefully preserved in the Williamson papers. They appear to have been written after Albro and Mary Joseph had salvaged what little they could from their ravaged

home. In the first one, Rode proposed to leave their clothing at the precinct until “everything will be settled.” His P.S. intimated that he was still not sure order had been fully restored in the city: “I have got three policemen watching your house to prevent fire, etc.” Lyons must have replied with another suggestion, for Rode’s second note reads in its entirety:

New York July 17th/63

Mr. Lyons

Sir

I have received yours from the bearer. And I cannot answer whether I can comply with it. I will see you this afternoon as I mentioned in the other note, as I have been excused from my Captain for that purpose. I cannot say to day what will occur to morrow. I will be at said Drug Store at 3 O’Clock P.M. this day with Horse & Wagon.

yours &

John W. Rode

Sergt. 4th Prect.

27

What had Lyons requested? And why did he suggest meeting at “said drugstore” in the middle of the afternoon when trouble was still possible? Whose drugstore was it? Could it have been Philip’s? If so, how could it have been a safe meeting place for a white police officer and a black victim gathering up his few remaining earthly possessions?

Strangely enough, during the riots Philip’s drugstore remained a safe place. His story never found its way into newspaper reports of the day. Maybe it was not deemed newsworthy enough, since it was not the story of a poor hapless black victim beset by a fiendish Irish mob. Or maybe it was deemed too newsworthy, because it might have alerted rioters to the fact that there was still more black property to be destroyed. But I found a full account of what happened in the Williamson papers. Family members must have told the story innumerable times, and it was undoubtedly repeated over the years by others. Williamson diligently recorded it, and he must have been the one who provided the

anecdote to the

New York Times

, which, eager to celebrate the life of “one of the best-known colored men in this city,” saw fit to print it in Philip’s obituary:

When the riot was at its height a crowd of men gathered at White’s store to defend it from attack. Mr. White was warned by some of the business men that he would be wise if he hid himself. He said: “What have I to fear? Even if these men here could not protect me, there are as many men among the rioters who would fight for me as there are those who would injure me.” Not the slightest attempt was made to harm him or his property.

28

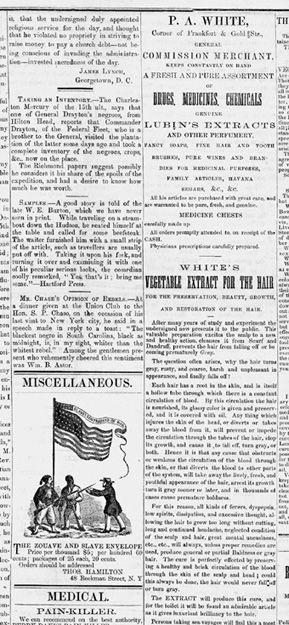

What made Philip so sure that the mob would harm neither his person nor his property? After all, he lived only a few doors down the street from the Lyonses at 40 Vandewater, and his drugstore was within a stone’s throw at the corner of Frankfort and Gold Streets. Like Lyons’s and Powell’s Sailors’ Homes, Philip’s pharmacy was an important landmark in the black community. First William C. Nell and later Frederick Douglass had praised it in newspaper columns of the 1840s and ’50s as proof of successful black entrepreneurship. By now, Philip was even more prosperous. In December 1861 and January 1862 he took out a series of advertisements in the

Weekly Anglo-African

, offering his customers goods of all kinds: “perfumery, fancy soaps, fine hair and tooth brushes, pure wines and brandies for medicinal purposes, family articles, and Havana segars”; “Badeau’s strengthening plaster for the lame or weak back, pain or weakness in the side, chest, stomach or limbs”; and “physicians prescriptions carefully prepared.” In particular, Philip promoted what appears to have been his own concoction: “White’s vegetable extract for the preservation, beauty, growth, and restoration of the hair,” which, he promised, would clean dirty and greasy hair, get rid of dandruff, restore circulation so as to prevent grayness or baldness, and ultimately produce “luxuriant brilliancy.”

29

Advertisement for P. A. White’s pharmacy,

Weekly Anglo-African

, December 21, 1861 (Houghton Library, Harvard University)

Here’s where Philip’s strategy of going along and getting along rather than raising a ruckus, of accommodation rather than protest, paid off. In contrast to Lyons and Powell, Philip had made his business integral—indeed

indispensable—to his local neighborhood. Douglass had noted that Philip’s drugstore was patronized mainly by the poor whites in his neighborhood. The

Times

obituary elaborated:

The Swamp neighborhood was quite thickly peopled when he went there, but he had a struggle for some years to keep afloat. During that time, however, he was never unmindful of the poor, and the services and material of his store were willingly given without pay to any one who needed them. …

His acts of kindness and charity were numerous, and scores of poor families were befriended and helped by him not only with medicines, but with food and money. Those whom he helped had a chance to show their gratitude during the draft riots of 1863.

Since his arrival in the Swamp in 1847, Philip had been determined to establish a viable local business. He put down roots. He got to know his neighbors, who were increasingly poor Irish. They knew him to be a hard worker. Even after hiring an apprentice, it’s quite likely that, given his methodical nature, Philip stood behind his prescription counter, helping to compound the drugs his customers so badly needed. My great-grandfather might have wanted to make money, but he was also dedicated to the art of healing, to bringing relief to a community ravaged by chronic poverty, malnutrition, and disease. So he was willing to give away medicines free or donate food and money when necessary. Under such circumstances, race, class, and ethnicity hardly mattered.

Philip’s neighbors had a stake in the survival of his drugstore. The

New York Times

obituary stated that Philip felt certain of the protection not only of those standing guard at his drugstore but also of “many men among the rioters.” The comment suggests that the mob was composed of men Philip knew, his poor Irish neighbors, prepared to destroy the property of other black New Yorkers—perhaps Powell’s or Lyons’s homes—but determined to “fight” for Philip’s.

My great-grandfather had achieved a delicate balance. He did so, I think, through a canny combination of altruism and calculation. I

imagine Philip’s drugstore as a meeting place in which he successfully brought together potentially antagonistic groups in his neighborhood united by need. And he forged a mutually interdependent relationship between himself and his poor Irish neighbors in which benevolence and self-interest were inextricably intertwined for the benefit of all concerned. By giving away medicines, Philip was helping to maintain the stability of the neighborhood in which he lived and worked, and to safeguard his own position in it. Accepting his benevolence over the years, his poor Irish neighbors were eventually able to repay him by protecting him during the riots. In so doing, they were also ensuring that the drugstore they depended on so heavily would survive the riots and continue to serve them.

Yet Philip’s balance was even more delicate than his neighbors imagined. The

New York Times

obituary had this to add about Philip:

His industry and obliging disposition won for him also the favor of business men in the Swamp, many of whom took pains to put trade in his way until he was firmly established. The opportunities thus opened to him inclined some wholesale orders which led him into that branch of the business. It soon became so profitable that he bought the store property and was rated prosperous.

He clung to the retail branch of his business even after he became a wholesale dealer, few in the neighborhood, indeed, knowing for some years that he had interests beyond the counter.

The methodical Philip had patiently built up strong business relations with white merchants in the Swamp, men whose interests were similar to his and whose property might also have been targets during the draft riots. Philip was much more than the small self-employed local tradesman his neighbors thought him to be. He was now engaged in the lucrative, but far more invisible and impersonal, business of a wholesale dealer. His advertisements in the

Weekly Anglo-African

reflected this change. Listing himself as a “wholesale dealer in drugs, dyes, patent or

proprietary medicines, fancy goods, perfumery,” Philip urged country dealers to buy from him, promising that his goods could not be undersold if paid for in cash.

30

In time, he was able to buy his store property.

But perception is all. To his poor Irish customers, Philip remained the hardworking shopkeeper whose generosity compelled their loyalty. To the businessmen of the Swamp, he was an entrepreneurial young man whose business prospects they were happy to further. To both groups, his drugstore contributed to the welfare of their neighborhood. They did not want it destroyed.

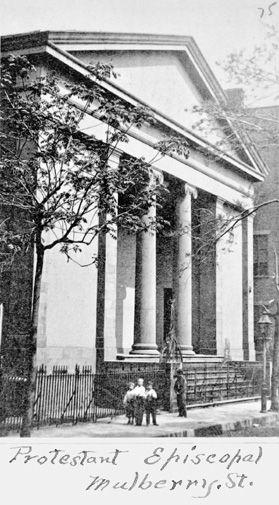

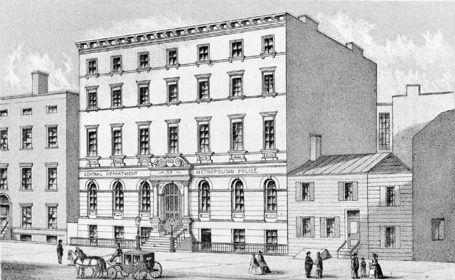

Philip, however, could not protect his beloved church. “Police Headquarters,” observed a

Tribune

report on July 23, “looks more like an arsenal than the great rendezvous of our Metropolitan force. United States soldiers and volunteers, regular and special policemen, stand at the corners of the streets that bound the edifice, and the African church in front of it swarms with soldiers.” This African church was none other than St. Philip’s, which, following the flight of blacks out of the Five Points district and other Lower Manhattan neighborhoods, had purchased a Methodist church building on Mulberry Street in the Fourteenth Ward and moved into it in 1857. Even though they still had few resources, parishioners continued to lavish the same care on their sanctuary as when they were located on Centre Street. They were determined to make the physical structure of their church reflect their sense of the divine, especially as envisioned by the Episcopal denomination. They formed a series of subcommittees, of which Albro Lyons was a member, to secure a chandelier for the new building and also to determine how best to alter the church’s chancel “to make it conform to the usage of the Protestant Episcopal Church.”

31

Metropolitan Police Headquarters, Mulberry Street near Bleecker, lithograph by A. Brown and Company (printed in

Booth’s History of New York

, volume 7, Emmet Collection, Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints, and Photographs, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox, and Tilden Foundations)