Black Gotham: A Family History of African Americans in Nineteenth-Century New York City (39 page)

Read Black Gotham: A Family History of African Americans in Nineteenth-Century New York City Online

Authors: Carla L. Peterson

They were, these men claimed, dispensing charity with kindness: “There are no harsh or unkind words uttered by the clerks—no impertinent quizzing in regard to irrelevant matters—no partizan or sectarian view advanced. The business is transacted in a straightforward, practical manner, without chilling the charity into an offense by creating the impression that the recipient is humiliated by accepting the gift.” But no different from the benevolence of the police and city officials, the merchants’ charity was accompanied by assumptions, expectations, humiliations.

The merchants assumed claimants to be imposters until proven innocent, or in their words, “worthy objects of charity.” They insisted on making personal visits “to ascertain the facts of the case … and save us from imposition.”

43

Only then were petitioners given a small stipend and jobs sought for them—as servants, of course.

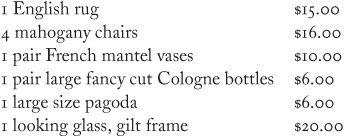

When the merchants argued that their gifts should not be construed as “humiliating,” they were in fact underscoring that that was precisely what they were: they suspected claimants of being frauds, took pains to emphasize their dependence, and pigeonholed them as a servile class. The humiliation must have been especially unbearable for men like Albro Lyons who over the years had accumulated considerable personal property. In the Williamson papers, I discovered Albro’s neat handwritten list of belongings destroyed or stolen by the mob. A bitter reminder of all that the family had lost, it gives some idea of their wealth and elite status:

The list goes on for pages. It even records the items that the Lyons children had lost. For Maritcha, it was her poplin, organdie, and French calico dresses, muslin skirts, a pair of kid gloves, and a workbox.

44

Still, Lyons must have considered himself one of the lucky ones. His claims were taken seriously. The Merchants’ Relief Committee awarded him $500 and the city $1,502.20.

More than anything else, the merchants wanted to ensure long-lasting social and economic stability in the city that would keep the lower classes—both blacks and whites—in their place. To that end, they recognized the necessity of black labor. They worried that if the city’s black population remained unemployed, it might become a permanent “pauper race” that would drain the city’s charitable institutions or, just

as bad, that white laborers from the country might flood into the city, thereby reducing wages, and becoming equally mired in poverty. At the same time, they expected black laborers, much like the Mulberry Street School students in the 1820s, to discipline themselves and “remember that true liberty is not licentiousness, it is obedience to law, it is cheerful compliance with the obligations imposed by society for the good of the whole.”

45

Following the model of the Mulberry Street School trustees, the merchants enlisted members of the black elite to help them carry out their cause. Just as Peter Williams, William Hamilton, and Thomas Sipkins had earlier visited the homes of black parents, so Garnet, Charles Ray, and John Peterson now visited black claimants to ascertain their needs. Once again, these men balanced humility with self-assertion. A month after the riots, Henry Highland Garnet presented the assembled merchants with an elaborate document engrossed on parchment by Patrick Reason and elegantly framed. In it, Garnet began by thanking the merchants profusely, comparing their charity to that of New Testament figures, the Good Samaritan in Luke and the righteous in Mark:

When we had fallen among thieves who stripped us of our raiment and wounded us, leaving many of us half dead, you had compassion on us. You bound up our wounds and poured in the oil and wine of Christian kindness and took care of us.

We were hungry and you fed us. We were thirsty and you gave us drink. We were made strangers in our own homes and you kindly took us in. We were naked and you clothed us. We were sick and you visited us. We were in prison and you came unto us.

But Garnet also made demands. In his conclusion he pointedly reminded the merchants that they had not yet fulfilled their obligations toward black New Yorkers. “Protect us in our endeavors to obtain an honest living,” he insisted. “Suffer no one to hinder us in any department of well directed industry, give us a fair and open field and let us work out our own destiny, and we ask no more.”

46

Another private entity, the newly formed Union League Club, responded to at least one of Garnet’s demands. Perhaps more than any other organization, it came closest to offering black New Yorkers meaningful reparations.

George Templeton Strong was among the founding members of the club. It would be a gross exaggeration to suggest that he had converted to abolitionism as Greeley had a few years earlier. But there was a shift in tone in his diary. Although he still called blacks “niggers,” he had at least come to see them as innocent, persecuted victims. “There is the unspeakable infamy of the nigger persecution,” he fulminated. “They are the most peaceable, sober, and inoffensive of our poor, and the outrages they have suffered during this last week are less excusable—are founded on worst pretext and less provocation—than St. Bartholomew’s or the Jew-hunting of the Middle Ages!” Strong now heaped all his contempt on Paddy, lumping all Irish into one indistinguishable mass of “biped mammalia … that crawl and eat dirt and poison every community they infest,” and ignoring the actions of individuals like Officer Kelly or Philip’s neighbors.

47

Strong was above all a Unionist, and support for the Union was the motivating impulse behind the Union League Club. The founders’ goal was to bring together prominent city men loyal to the federal government and dedicated to the preservation of the Union. Its core members were descendants of the country’s first settlers, men of colonial stock. They planned to gather around them an elite cadre of professional men, scientists, writers, artists, and intellectuals. They would also seek out representatives of the younger generation and train them to be the nation’s future leaders. The club’s membership was eclectic. There was Strong. There was the China trader Abiel Abbott Low. There was Robert Minturn, son of the old shipping magnate and the club’s first president; although an antislavery Whig, he had chosen to vote for the Democratic presidential candidate James Buchanan in 1856, and had made noises in favor of conciliation with the South. Yet other members included Superintendent of Police Kennedy and men like John Jay and Peter Cooper who had long supported black New Yorkers.

48

It seems passing strange that George Templeton Strong and John Jay belonged to the same club. Jay had been a committed abolitionist for as long as anybody could remember. Many of his views must have struck his peers as intemperate. He was convinced that the draft riots were a Confederate plot hatched in Richmond for the purpose of turning New York into a rebel city. Like Henry Highland Garnet, he had been an early proponent of military service for blacks. “To arms!” he called out in the July 10, 1862, issue of the

Weekly Anglo-African.

“Lose not a moment, but be ready promptly to meet the call of our common country—organize yourselves in companies at every convenient point—obtain drill masters—practice the manual exercise and evolutions steadily and with a will—accustom yourselves to the prompt obedience of military discipline … that companies … may be speedily filled when the order comes for you to march.”

49

In 1864, the Union League Club rushed to make this call a reality.

Union and Disunion

CIRCA 1864

BLACK NEW YORKERS WERE

energized. They had found allies—predictable and unpredictable—within the white community and believed that, as they worked together, freedom, citizenship, and national reconciliation would soon be more than a promise. Almost immediately, however, they faced a dizzying cycle of acceptance and rejection, union and disunion, both in the nation and in their own community.

After the riots, Union League Club members decided to do the unthinkable and recruit a black regiment, ultimately raising three: the Twentieth, Twenty-sixth, and Thirty-first Regiments of the United States Colored Troops. Filled with pride, they documented their efforts in an extensive

Report of the Committee on Volunteering.

New York’s black leadership threw them their full support. Governor Seymour promised not to interfere. Overcoming its initial reluctance, the War Department agreed to set up living quarters and a drill ground for black soldiers on Riker’s Island, which was then federal property.

At first, problems abounded. Men were tricked into service with the promise of lucrative civilian jobs such as coachman, then drugged, and forced onto Riker’s Island. There, they crowded into old, worn tents

where the cold inexorably seeped in. They were overcharged for coffee and water. Disease spread. Although disqualified from official service because of his amputated leg, Garnet was made honorary chaplain. He brought a measure of order to Riker’s. Enthusiasm soon ran high. Even Strong got behind the effort. “Rumor of a Corps d’Afrique to be raised here,” he wrote in his usual cynical way soon after the proposal was aired. “Why not? Paddy, the asylum-burner, would swear at the dam Naygurs, but we need bayonets in Negro hands if Paddy is unwilling to fight for the country that receives and betters him.” Once the regiment was raised, Strong was proud of what his club had done. “Our labors of a year ago have borne fruit. The Union League has done something for the country.”

1

On March 5, 1864, the Twentieth Regiment left Riker’s Island for Manhattan. The soldiers marched from the East River to Union Square, where they stopped for a flag presentation ceremony. Unlike the Emancipation Day parade of July 4, 1827, this was not a black affair, but a public event that brought together blacks and whites, men and women. Led by Superintendent Kennedy, one hundred policemen, members of the Union League Club, and their friends, the soldiers paraded down the streets. They made, according to the

Tribune

’s lengthy account, “a fine appearance in their blue uniform, white gloves, and white leggings. They are hearty and athletic fellows, many of them six feet tall, straight, and symmetrical.” The crowd, the

Tribune

continued, was truly representative of the entire city, as “citizens of every shade of color, and every phase of social and political life, filled the square, and streets; and every door, window, veranda, tree and house-top that commanded a view of the scene was peopled with spectators.” Few, if any, white racists threatened trouble. Cheers replaced jeers.

At the ceremony, Garnet and other black leaders sat on the podium alongside members of the Union League Club and city dignitaries. Charles King, president of Columbia College, made a speech that must have thrilled black New Yorkers’ hearts in its extension of the sentiments of the Declaration of Independence to all black Americans: “You are in arms,” he intoned, “not for the freedom and law of the white race alone, but for universal law and freedom; for the God implanted

right of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness to every being whom He has fashioned in his own image.” What was this statement if not recognition of shared humanity and a promise of citizenship? On another platform erected in front of the Union League Clubhouse sat the wives, sisters, and daughters of club members. They had painstakingly stitched a flag for the regiment and requested that Charles King present it during the ceremony. He did so, and in his speech he praised them as “loyal women,” their purpose as “patriotic,” and their commitment to create a “sacred banner” second only to “the religion of the altar.”

Black New Yorkers were elated. Their men were finally being given the chance to fight and show proof of their capacity for citizenship. The entire city seemed to be coming together in a show of racial reconciliation, all the more astonishing since, as Charles King reminded his audience, a mere few months earlier “the homes of these soldiers were attacked by rioters, who burned their dwellings stole their property, and made the streets smoke with the blood of their unoffending relatives and friends.”

2

Circumstances had indeed changed, but many patterns remained intact. White elite men were still extending benevolence to black men from whom they then expected gratitude as well as to their womenfolk on whose behalf they spoke. Moreover, it’s not at all clear what was going through the minds of white working-class men and women observers.

If you confined your reading to the

Tribune

, it would not be clear what black women were up to either. If you perused the Union League Club’s

Report

, it would appear that they were content simply to express “sincere gratitude for the great and good work” of the club. But black women were far from idle. In the mid-1850s, their efforts on behalf of the Colored Orphan Asylum had thrust them into public life; now they were broadening that work to include those affected by the war. In late 1863, men of the black elite—among them members of my family, Peter Guignon, Peter W. Ray, and Albro Lyons, and their friends James

McCune Smith, Charles Reason, George Downing, and John Peterson—had established the American Freedmen’s Friend Society to raise money and collect clothes for black soldiers and emancipated slaves. Women of the older generation, like Cornelia Guignon, as well as of the younger, which now included Elizabeth Guignon and Maritcha Lyons, held fund-raising fairs. They sold articles to benefit the freedmen, set up a wheel of fortune for entertainment, offered ice cream to the hungry, hoping “to move many a dollar in the right direction.”

3