Blood on the Tracks: A History of Railway Crime in Britain (7 page)

Read Blood on the Tracks: A History of Railway Crime in Britain Online

Authors: David Brandon,Alan Brooke

These pictures were removed, framed and placed on the walls of homes right across the country. It is ironic to think that originals in good condition are now worth a King’s ransom. One enterprising fellow found that furniture makers would pay good prices for horsehair. The railways stuffed their seats with this material and so he raided Great Central Railway carriage sidings just outside Marylebone station in London, walking off with sacks of horsehair – until the police caught him.

The railways need all manner of materials for their infrastructure and their operations, and many of these were, or still are, well worth the trouble of stealing. It is by no means unknown for stations and other buildings to have the lead stripped from their roofs. Canvas sheets and tarpaulins used to be required in vast numbers for covering freight wagons. They were also wanted illicitly for a wide range of other, non-railway, purposes, hence there was always a ready sale for these items. The farming fraternity in particular found them extremely useful for covering clamps of root crops and haystacks, for example. In 1951 the Eastern Region of British Railways had over 10,000 sheets missing and it was probably no coincidence that it served an area where there were large amounts of arable land.

Steam locomotives had copper fittings which were always worth stealing. When steam locomotives were being withdrawn in huge numbers in the 1960s they were frequently stored in sidings awaiting the call to be scrapped.

Obscure rural locations were often found with a view to avoiding the attention of metal thieves, but usually with little success, and the valuable portable non-ferrous parts might be removed and spirited away quickly and quietly. Lots of so-called railway enthusiasts entered engine sheds and brazenly stole number plates and nameplates, the latter in particular sometimes fetching five-figure sums in the twenty-first century.

The huge steam engine ‘graveyard’ at Barry Docks in 1970. These hulks rusted away for years, stripped of anything removable by genuine preservationists and also trophy-hunters. Miraculously many of these locomotives were rescued and have been restored to working order on Britain’s heritage railways.

A real bonanza for the criminal community was the development of electric traction and electric signalling, because these both used substantial amounts of copper. Conduits containing copper wire for signalling purposes run by the track through both town and country. Especially in the more rural areas these were, and remain, a tempting target for well-equipped thieves, causing signalling failures and considerable aggravation, not least because of the delays caused to trains. In 2007 the theft of valuable metal from railway property caused more than 2,500 hours of delay to train services, never mind the cost of replacing the materials involved.

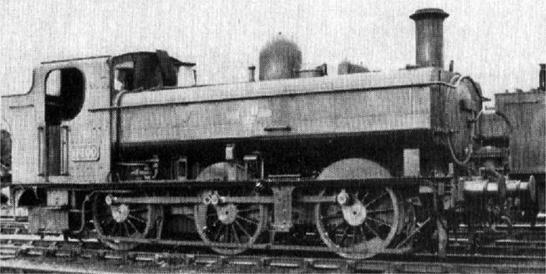

No.6400, a 64xx 0-6-0PT of the sort that was hijacked from Wolverhampton Stafford Road engine shed. These diminutive locomotives were introduced in 1932 by the Great Western Railway and designed for working light passenger trains, particularly on branch lines. The Great Western Railway had huge numbers of locomotives of basically the same design and they were often referred to by enthusiasts as ‘matchboxes’; sometimes with affection but otherwise with low-key contempt, probably because they were so commonplace.

There have been attempts over the years to joyride on locomotives. One such incident occurred in January 1961 when a small 0-6-0 Pannier Tank numbered 6422 was stolen from Stafford Road shed at Wolverhampton by a former fireman who, at the time, was wanted by the police for questioning in connection with a robbery. At dead of night he found the locomotive unattended, told the man controlling the exit road that the engine was on its way to Worcester Works for maintenance purposes and set off along the main line.

He chugged merrily along through the night, being passed from one signalling section to the next without any suspicion being raised, and he even halted at Stourbridge Junction to take on water. At Droitwich, No.6422 was switched into the loop in order to allow a fast fitted freight train to overtake it. For whatever reason the locomotive was abandoned there and the fireman ran away into the dark. One version of the story goes that back at the shed, no one realised that No.6422 was missing until a footplate crew turned up early in the morning to prepare it for a passenger turn. They searched the shed high and low and then reported to an incredulous foreman that they could not find it.

Another version is that the fireman had followed the correct procedure at Droitwich and had gone to the signal box to sign the train register. Soon afterwards the firemen disappeared into the night, and with the fast freight having gone past the signalman gave No.6422 the road. When the engine did not move the signalman investigated and found that, incredibly, it had had no crew! He then reported his discovery to control. The fireman was charged

with obstruction and theft – not of the locomotive but of the coal that was used to get it to Droitwich.

At Chester General one October day, also in 1961, train spotters were admiring a Stanier ‘Coronation’ 4-6-2 No.46243

City of Lancaster

at the south end of the station when a Churchward ‘Mogul’ No.7341 appeared light engine from the direction of Chester Midland shed. Train spotters were used to such movements, but one of them spotted that this was different – there was no one on the footplate! Fortunately the locomotive was travelling slowly and station staff were quickly alerted and able to bring No.7341 to a halt. The authors have been unable to ascertain whether the cause of the runaway was negligence on the part of the footplate crew or someone wilfully either starting to take it for a joyride and then, getting cold feet, abandoning the engine to its own devices. It seems extraordinary that there were no conflicting points and that it managed to get as far as it did.

A disgruntled anonymous railwayman based at Crewe North engine sheds used to send letters to the management of the London & North Western Railway saying that he was going to ‘liberate’ one of their locomotives by releasing it to chug off along the line by itself. As was intended, this caused chaos on the line and, fortunately only on one occasion, it led to serious injury to a railwayman. The miscreant managed this operation no fewer than nineteen times before attempting it once too often being arrested, charged, found guilty and sentenced to a term in prison. He was an engine driver who obviously had the requisite skills but he never revealed the reasons for his irresponsible behaviour.

Over the years railway offices have consistently received the attention of burglars determined to rifle safes for the day’s takings, or extract parcels and packages with valuable contents. These could be highly lucrative. A break-in at Berkhamsted in Hertfordshire in 1956 meant that the robbers left

£

500 better-off. At least one such burglary nearly ended tragically. In February 1956 a police officer apprehended and arrested two men engaged in robbery at a goods depot at West Hartlepool. They stabbed him, inflicting life-threatening injuries, but fortunately he survived. The two men involved therefore faced far less serious charges than if the injuries had been fatal.

A number of stations and other railway buildings, particularly those in rural locations, have attracted the attention of a different kind of thief – the stripper of lead – especially from roofs. Such criminals were no mere opportunists but needed to be well organised, having transport and all the equipment necessary to carry away their extremely heavy but valuable booty. Coins of the realm are usually heavy and bulky relative to their value but this has not deterred a number of light-fingered characters whose criminal speciality was

breaking into the coin machines that controlled entry to the cubicles in station toilets.

A recent view of Berkhamsted station, Hertfordshire. It is good to see handsome old buildings like these adapted for modern use. A lick of paint would not go amiss though.

The vulnerability of stations to breaking and entering is shown by the fact that in 1961 British Transport Police recorded no fewer than 352 cases of such criminal enterprise. The fact is that just about anything not nailed down was, or still is, grist to the mill of petty and professional thieves on or around railway premises. Actually, nailing it down has never been a guarantee it would not be stolen. If it is valuable, it is also vulnerable.

One extraordinary robber enjoyed a criminal career of several months in the 1930s. He was a young man employed on the London & North Eastern Railway as an engine cleaner. For reasons best known to himself he hit on the idea of taking a railway journey in an otherwise empty compartment, and when the train was in motion he would open the door and embark on a daredevil walk along the footboards, deriving great amusement from the looks of startled amazement on the faces of the passengers as he leered at them through the carriage windows. In fact it was so much fun that he did it

several times but then decided that the acrobatic stunt could be put to more profitable ends.

‘Take the front cab in the rank, please.’

Equipping himself with an imitation firearm and wearing a highwayman’s mask, he clambered out on the footboards once more and made his way along the outside of the train until he found a traveller alone in a compartment. Such a passenger would have been understandably terrified as someone resembling Claude Duval opened the carriage door, clambered in and demanded money with menaces. Amazingly, he managed to carry out a number of these robberies, but he did so once too often and was caught.