Blood on the Tracks: A History of Railway Crime in Britain (9 page)

Read Blood on the Tracks: A History of Railway Crime in Britain Online

Authors: David Brandon,Alan Brooke

They revealed that on the night of the murder, Muller had, unusually for him, not returned by eleven o’clock. They had waited up but decided to go to bed, and Muller had clearly let himself in and must have gone to bed in his usual quiet manner. When he came down to breakfast he was his normal cheerful, even charming, self. He was a model lodger described as well-behaved and inoffensive, and the Blyths had been sorry to see him go. On the day after the attack on Briggs Muller had stayed in all day and had gone out with the Blyths that evening. The next day, Monday, he had shown the Blyths a gold chain which he said he had bought cheaply from a man who worked on the docks.

The police were soon gathering a lot of useful information. Matthews and his wife were able to confirm that the crushed beaver hat did indeed belong to Muller. From a German couple called Repsch, living in Aldgate, they learned that Muller had arrived from Cologne about two years previously and they had helped him to get a job working for a tailor in Threadneedle Street. He had been a good worker but he had left on 2 July, stating his intention of emigrating to the USA where he thought he could make a fresh start.

The last time Repsch had seen Muller he had been in high spirits, showing off a watch and chain and a ring which he said he had bought for a good price from a man on the docks. He was also wearing a very fine hat which they had not seen him wearing before. He told them that his other one had been damaged and that he had obtained a replacement of a very superior sort at a bargain price.

Another witness to whom the police spoke was John Hoffa, a friend and workmate of Muller. When Muller had left his digs with Mr and Mrs Repsch he had lodged for a few nights with Hoffa in his room before making for the London Docks to board

Victoria.

With these and various other snippets of information, Tanner and Clarke now felt that there was a case against Muller. At the very least they needed to get hold of him so that he could ‘help them with their enquiries’, a wonderful euphemism.

Late on the Tuesday afternoon they went to the Chief Commissioner of Police who recognised the need to act quickly, especially in the light of public outrage about the atrocity and the necessity of bringing its perpetrator to justice. He authorised the two officers to sail to New York from Liverpool on the

City of Manchester

, a steam vessel and a much faster ship, in order to be there to arrest Muller when

Victoria

docked. The seriousness with which this case was being taken was indicated by the fact that Robert Death and Matthews accompanied Tanner and Clarke in order to confirm Muller’s identity when he was apprehended. The police even gave Mrs Matthews, who had four young children, financial compensation for the loss of her husband’s earnings while he was being a good citizen enjoying an expenses-paid passage to New York and back.

New York was buzzing with excitement about the murder, and its citizens were very taken up by the idea that Muller was crossing the Atlantic in order to evade justice, and that following hotfoot and actually overtaking the oblivious Muller was the epitome of cutting-edge technology, a steamship, carrying doughty British detectives determined to bring their quarry to justice. In fact so excited were some New Yorkers that a boatload of them sailed past

Victoria

as she was entering harbour shouting out phrases like, ‘How are you, Muller the murderer?’ Fortunately for the authorities, Muller apparently did not hear the commotion they made.

Muller must have been musing about the opportunities that the New World would provide for an enterprising young fellow like himself as his ship neared its destination.

Victoria

docked on 26 August. Blissfully unaware of the nemesis bearing down on him as he waited to disembark, no one could have been more surprised than he when a couple of New York uniformed policemen, and a pair of what were clearly English plain-clothes detectives, shouldered their way through the crowd and arrested him.

He was taken below and he and his belongings were searched. On his person were Briggs’s gold watch and silk hat which had been slightly altered by Muller. The police officers learned that Muller had made something of a name for himself on the voyage by his truculent and overbearing manner, and had come off second best in a fight with a fellow passenger who he called various rude names. Muller for his part received a corker of a black eye. Fights among the bored passengers on the long voyage were by no means uncommon, but

Muller had also drawn attention to himself by betting that he could eat five pounds of German sausages at one sitting. He laid the bet in order to raise some money but failed in this culinary marathon and, having no cash, paid his debt with two shirts. It seems there had not been a dull moment while Muller was on board!

After the positive identification that was required, extradition proceedings were started, but they quickly ran up against an unexpected snag. There were many rich and influential people of German origin in and around New York and they took up Muller’s case, arguing that he was beyond the jurisdiction of the British courts and British police. One argument was that in the USA a person was presumed innocent until proven guilty, whereas Muller had been chased halfway across the world, intimidated by the police and the legal authorities, and was now being threatened with extradition as if the case against him was already decided.

It should be remembered that the general mood of people in the north of the USA was hostile to Britain, because many wealthy Britons supported the Confederate cause in the American Civil War. In fact Britain and the USA were almost in a state of undeclared war.

However, extradition formalities were eventually concluded on 3 September, and Tanner and Clarke embarked on

Etna

with Muller in handcuffs and with Matthews and Death, who had been revelling in the experience of a lifetime, something to tell their grandchildren about – all at public expense. Even Muller clearly enjoyed his voyage back to Blighty. Travelling in

Etna

was a much more luxurious experience than steerage in

Victoria

, and Muller did not stint on the best cuisine that the ship’s galley could provide. Neither did he waste his time in between meals. He got to grips with, and completed, a reading of

Pickwick Papers

and

David Copperfield

.

The ship docked at Liverpool on 16 September and, after staying in the city overnight, the party travelled down to London via Crewe and Rugby on the main line of the London & North Western Railway. It was Muller’s last journey by train. He was unprepared for the reception he received when he got to London, where ravening crowds jeered and booed him as he was taken first to Bow Street Magistrates’ Court where he was committed for trial and then to Holloway Prison.

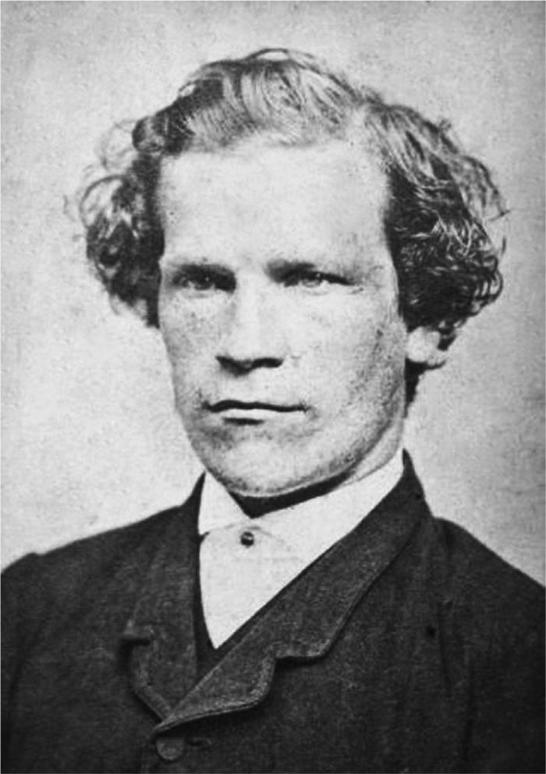

The trial at the Central Criminal Court, better known as the Old Bailey, began on 27 October 1864. Muller looked small, even frail, and was neatly turned out. He spoke confidently when required and was punctilious with regard to the court’s etiquette. He certainly did not look like a man capable of launching a murderous attack on Briggs who may have been considerably older, but was also larger, strongly built and very fit for his age. If Muller had had an accomplice, who was he? Was it Muller and the second, unknown man who Lee had seen at Bow, sharing the carriage with the defendant? He

stubbornly stuck to the assertion of his total innocence and refused to implicate anyone else.

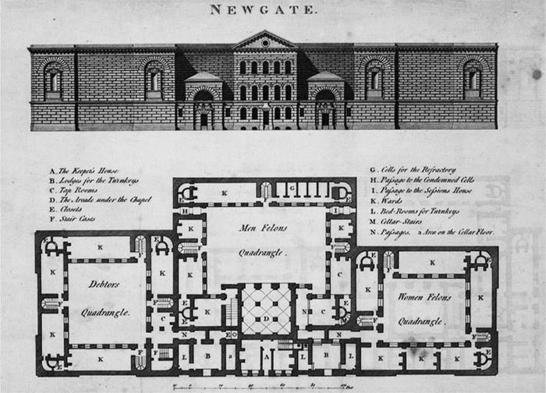

The frontage of Newgate Prison. Over the years up to 1868, this hated building housed tens of thousands of felons, eking out their miserable last days before going off to be executed at Tyburn, near the present-day Marble Arch. After 1783 they were executed instead outside Newgate in the street known as Old Bailey.

The witnesses for the prosecution were a motley and unimpressive lot whose reliability and integrity were effectively called into question by the counsel for the defence. The evidence was largely circumstantial but the jury found him guilty, taking just fifteen minutes in their deliberations. The German community in Britain now moved into action, protesting that there had been a miscarriage of justice, producing petitions and pleading for clemency.

However, the time of the execution was set for eight in the morning of 14 November. The location was outside the hated Newgate Prison. The executioner was William Calcraft. He had started his grisly work in 1829 and, despite a long career in the terminatory business, as it were, he was never much of a craftsman and he was unpopular not only with his victims, which was understandable, but also with hanging aficionados. This was because his estimation of how much drop to use for each hanging was poor, and many of

those whose lives he terminated took longer than necessary to die. Even those who attended every possible hanging believed that the executioner had the responsibility to minimise the condemned prisoner’s sufferings.

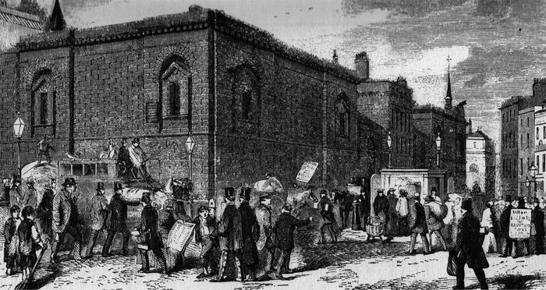

Preparations being made for an execution outside Newgate Prison. Such events often took on the character of a popular carnival, especially if the condemned prisoner was especially hated for the nature of his crimes, or equally for perverse reasons, admired by the gallows crowd.

The crowds that gathered at hangings were known for being boisterous and badly behaved, but the impending death of Muller seems to have attracted the most bestial and wretched of London’s population, totalling something like 50,000, baying for blood and avid for entertainment. As

The Times

reported, the crowd went quiet only as Calcraft did his work and Muller’s life ebbed away, when there was an awed hush. For the rest of the time there was ‘loud laughing, oaths, fighting, obscene conduct and still more filthy language’.

In fact so horrible was the behaviour of the crowd at the execution of Muller that the event undoubtedly contributed greatly to the developing feeling that executions should be made private affairs behind prison walls. Indeed it was only three years later that the last public hanging in England took place, again outside Newgate Prison.

It has entered the annals of folklore that Muller was goaded into making a last-minute admission of guilt by the pastor attending him. Whether or not

this is true, it is unlikely that any modern court would have passed such a verdict with the forensic and other investigative techniques now available.

Franz Muller.