Blood on the Tracks: A History of Railway Crime in Britain (8 page)

Read Blood on the Tracks: A History of Railway Crime in Britain Online

Authors: David Brandon,Alan Brooke

The Murder of Thomas Briggs

W

here better to start than with the first murder on a moving train in Britain? This provoked what – up to then – was the greatest manhunt in British legal history.

You have to imagine Mr Thomas Briggs. He was an aldermanic figure, the epitome of Victorian middle-class respectability. In 1864 he was sixty-nine years of age, tallish, silver-haired, immaculately dressed and sporting a flowing white beard. Altogether, he was a most distinguished-looking gentleman. He was the chief clerk of Robarts, Lubbock & Co., a banking house in the City of London, a position which he had only obtained through a long career of diligent duty and unassailable probity.

He was wearing the kind of clothes he normally wore when travelling to and from work. These included a distinctive high silk hat. He also had an expensive-looking gold chain stretched across his capacious midriff, the chain being attached to a fine gold watch in his waistcoat pocket. He carried a bag in one hand, and a stout walking stick in the other.

On 9 July 1864, a Saturday, he left the office around half-past four and travelled to Peckham, south of the Thames, for dinner with his niece and her husband. Briggs was a widower and he made the pilgrimage to No.23 Nelson Square, now Furley Road, every week. They ate well. They always did. It was still light at half-past eight when he left, his bag now empty because its contents had consisted of little presents for the niece of whom he was very fond. He boarded a horse-bus back to King William Street in the City. He then walked briskly (that was his way; he was very fit and strong for his age), to

Fenchurch Street station where he climbed into a first-class compartment on a train of the North London Railway.

He caught the train with a couple of minutes to spare but no one else joined him in the compartment at Fenchurch Street. The train pulled out five minutes late at 9.50p.m. to start the roundabout route to his destination at Hackney via Shadwell, Stepney and Bow. Much of the route ran on low viaducts which gave a bird’s eye view of the rooftops of poor inner-city housing and the myriad of small, often rather noxious, industrial premises and workshops then so characteristic of that part of London’s East End. Hackney, however, was a cut above, boasting a respectable gentility.

The North London Railway had only just over thirteen miles of its own line, but its trains also ran on over fifty miles of line belonging to other companies. The North London Railway had an importance out of all proportion to its size because its small network linked the main lines coming into London from the north and west with the City and with the docks in the east. Its first London terminus was at Fenchurch Street via the circuitous route taken by the train conveying Briggs, but later it opened up services running more directly into the Broad Street terminus. This was a substantial station adjacent to Liverpool Street and which stood where the Broadgate development now is.

It may have been a small company but it was a proud one, and it had little time for the lower end of the travel market. Until 1875 it only catered for first and second-class passengers. It possessed a fleet of small but powerful 4-4-0 tank engines and its four-wheeled carriages were quite luxurious by the standards of the time.

It was a warm evening and almost totally dark as the train trundled along. A weak light in the ceiling provided only partial illumination. Briggs had worked all day, had eaten well, and was dozing fitfully. At Bow he exchanged brief pleasantries through his open carriage window with an acquaintance called Lee, who later averred that there were two other passengers in the compartment. One he described as thin and dark, the other as stoutish, thickset and lightly whiskered. Lee remembered being mildly surprised to see Briggs travelling at such a late hour. He was also surprised by the appearance of the other occupants of the carriage; they did not look like first-class passengers. Later, when he was in the witness box, he admitted that he had had a drink or two in a local pub. The general feeling in court was that ‘a drink or two’ actually meant several, or even many, drinks.

The train pulled out of Bow, being due to arrive at the next stopping place, Victoria Park, Hackney Wick, in a few minutes. The train was now four minutes behind time. The next compartment to that occupied by Briggs was also first class and was occupied by a draper called Withall and a female traveller. They were not together. As the train was approaching Hackney, Withall

described how he heard a sudden and strange howling noise, reminiscent of a dog in distress. His unknown female companion made a remark to the same effect. In another compartment close by, a female passenger had the unpleasant experience of being spattered with drops of blood that came in through the open window. She later said that she had heard no untoward noises.

When the train arrived at Hackney, two young men-about-town, Henry Verney and Sydney Jones, were waiting to join the train to travel to Highbury, and they stepped into the compartment in which Briggs had started his journey. It was empty but, although it was very poorly lit, they soon realised that a lot of blood was scattered around the compartment. A number of personal items could be seen. These were a black leather bag and a walking stick. Under the seat lay a black beaver hat, so squashed that it looked as if someone had stood on it. Thoroughly alarmed, they managed to get the attention of the guard who directed them to another compartment.

The guard was intensely irritated by this turn of events. The train was already late and the North London Railway prided itself on the punctuality of its trains. He gave the compartment a quick visual going-over, enough to make it obvious to him that it had very recently witnessed foul play. He locked the compartment and gave instructions for a telegraph message to be sent to the superintendent at Chalk Farm, the station where the train terminated. There the carriage was uncoupled and shunted into a siding to await examination by the police.

Meanwhile the driver of a train proceeding in the opposite direction saw a dark object lying close to the track near the bridge over the ‘Duckett Cut’. This waterway, more correctly known as Sir George Duckett’s Canal, joined the Lea Navigation to the Regents Canal at Old Ford. It had opened in 1830. The train was brought to a halt and the guard, engine driver and firemen all descended to track level to investigate. They found that the object was the body of a man, battered, bloodied and still alive, although only just.

With considerable difficulty, they carried him down to the street where they were fortunate to encounter a police officer going around his beat. He summoned assistance and a doctor was soon on the scene. His initial impression was that the injuries on the left-hand side of the man’s head had probably been sustained by his fall from a train. However, two violent blows had fractured his skull. Briggs’s inert body was first of all taken to a nearby pub which did unusually good trade as the news got around. It was later transported to his home in Clapton Square where he died late the next evening. He never regained consciousness.

This horrible murder stirred up a hornets’ nest of outraged headlines and articles in the newspapers. ‘Murder on the Iron Way’ thundered one newspaper truthfully, while another, tending more to hyperbole asked, ‘Who is safe? If we

may be murdered thus we may be slain in our pew at church, or assassinated at our dinner table’. This first railway murder emphasised just how vulnerable passengers in compartments could be to the depredations of malefactors, even in the biggest city in the world.

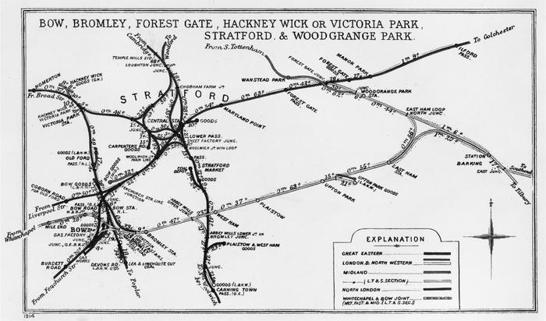

A map of the nineteenth-century railway network in London’s East End. The line carrying Muller and Briggs enters from Fenchurch Street on the bottom left and then proceeds through Old Ford and Homerton. Note the complexity of the lines in the Bow and Stratford areas.

They dared not leap from the train while it was in motion. They had no means of stopping the train. It was not easy to attract the attention of the guard or the men on the footplate. Without a side corridor in the carriage, it was hard to attract the attention of travellers in other compartments. Equally there was little that such travellers could do even if they had been alerted to possible trouble. Now two passengers travelling in the same compartment, but who were strangers, would spend the journey eying each other up suspiciously, making sure valuable possessions were out of sight. The manufacturers of coshes, then generally known as life-preservers, now had their workers slaving away feverishly on overtime in order to keep up with demand.

Inspector Tanner and Sergeant Clarke were appointed to the case and were soon certain that the motive for the attack had been robbery. On being examined, the compartment in which Briggs had travelled showed all the signs of having witnessed a murderous assault. Splashes and even pools of blood were on the floor and on the seats. A small travelling bag and a stout walking stick were to be seen under the seat. There was some bloody smearing on the silver

knob of the stick. The crushed beaver hat lying on the floor was examined. It had a maker’s name. The address was 49 Crawford Street in Marylebone.

It was quickly established that Brigg’s valuable gold watch and chain were missing as well as his high silk hat, a ‘topper’, itself valuable – there was always a ready black market for such expensive fashion items. However, a diamond ring, a silver snuffbox, four sovereigns and some small change had not been taken, suggesting that Briggs’s assailants, if there were two of them, had not had time to complete the robbery. It seemed likely that the crushed beaver hat belonged to one of the assailants. They thought that the missing hat belonging to Briggs would prove easy to trace. He had had it specially made by a well-known hatter in Cornhill, in the City. The beaver hat was also distinctive, having a low, flat crown and was rather downmarket compared with Briggs’s headwear. Descriptions of the missing items were circulated along with appeals for information.

At first the only lead seemed to be provided by a Robert Death who, perhaps understandably, pronounced his name as ‘Deeth’. He worked in a jeweller’s and pawnbroker’s shop in Cheapside, not far from where Briggs was employed in Lombard Street. The shop was run by his brother and the name ‘Death’ was used in advertising and packaging.

He told Tanner and Clarke that on the morning of 11 July, that is, the first working day after the attack on Briggs and his subsequent death, a young, somewhat sallow man with a foreign accent came into the shop and exchanged a rather fine gold watch chain for another watch chain and a ring which came to the same value. Something had struck him as fishy about the young man and the transaction they had carried out. Reading about the robbery and subsequent murder in the newspapers, he decided to talk to the police.

It was not much of a start. For a whole week little further information came in and the trail, if indeed it had ever existed, seemed to have gone cold. A week later, on 18 July, it suddenly got much hotter owing to the sharp-wittedness of a London cabbie by the name of Matthews. He was waiting for business in the rank outside the Great Western Hotel which fronted Paddington station. The cabbies had been buzzing – as indeed had all of London – with rumours and speculation about the sensational murder just over a week previously.

They were discussing a poster, of which there were thousands plastered over London, giving such details as were known about the murder and offering a reward of

£

300 for information that would lead to the arrest of the miscreant or miscreants involved. Matthews read the poster, seemingly for the umpteenth time, when suddenly something clicked. The poster mentioned Robert Death, the jeweller’s assistant and the foreign-sounding client. The same name ‘Death’ had been inside a small box presented to his daughter a few days earlier by a young German man she knew. His name was Franz Muller and he frequently wore a beaver hat. He had at one time been engaged to another of Matthews’s daughters.

All this came to Matthews in a rush, and, mixing good citizenship with licking his lips at the prospect of a reward, he set off immediately for his home in the Lisson Grove area to see if he could find the box that Muller had given to his daughter. He found it and took it to the local police station. He gave the police a description of Muller, and even a photograph, which got them quite excited. They became less excited when he told them not to bother searching London for Muller because he had just left England for New York and a new life in the United States of America. This was something he had apparently been talking about for a while. When Death was shown the photograph of Muller, he felt almost certain that it was the foreign-sounding young man he had done business with.

However, the police now had something to work on, and they quickly found out that Muller had pawned a number of objects, including the watch chain he had obtained from Death’s shop in order to raise the fare as a steerage passenger on the sailing ship

Victoria

bound for New York from the London Docks. They also discovered that he had written a letter just after the

Victoria

had put to sea which had been delivered to a married couple living in Old Ford with whom he had lodged for several weeks. They went to see the couple whose surname was Blyth.