Body Language: How to Read Others' Thoughts by Their Gestures (18 page)

Read Body Language: How to Read Others' Thoughts by Their Gestures Online

Authors: Allan Pease

Tags: #Popular psychology, #Advice on careers & achieving success, #Psychology

Seated Body Formations

Take the following situation: you are in a supervisory capacity and are about to counsel a subordinate whose work performance has been unsatisfactory and erratic. To achieve this objective, you feel that you will need to use direct questions that require direct answers and may put the subordinate under pressure. At times you will also need to show the subordinate that you understand his feelings and, from time to time, that you agree with his thoughts or actions. How can you non-verbally convey these attitudes using body formations? Leaving aside interview and questioning techniques for these illustrations, consider the following points: (1) The fact that the counselling session is in your office and that you are the boss allows you to move from behind your desk to the employee’s side of the desk (the co-operative position) and still maintain unspoken control. (2) The subordinate should be seated on a chair with fixed legs and no arms, one that forces him to use body gestures and postures that will give you a better understanding of his attitudes. (3) You should be sitting on a swivel chair with arms, giving you more control and letting you eliminate some of your own giveaway gestures by allowing you to move around.

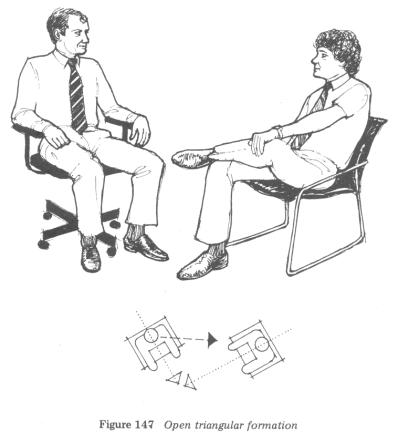

There are three main angle formations that can be used.

Like the standing triangular position, the open triangular formation lends an informal, relaxed attitude to the meeting and is a good position in which to open a counselling session (Figure 147). You can show non-verbal agreement with the subordinate from this position by copying his movements and gestures. As they do in the standing position, both torsos point to a third mutual point to form a triangle; this can show mutual agreement.

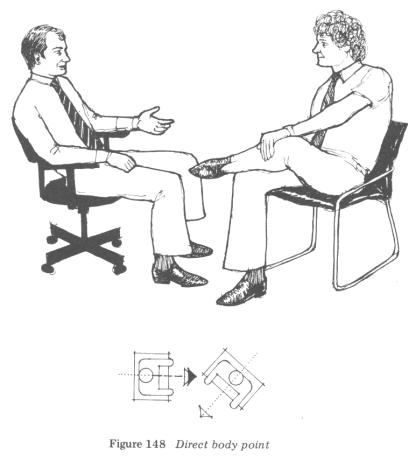

By turning your chair to point your body directly at your subordinate (Figure 148) you are non-verbally telling him that you want direct answers to your questions. Combine this position with the business gaze (Figure 149) and reduced body and facial gestures and your subject will feel tremendous nonverbal pressure. If, for example, after you have asked him a question, he rubs his eye and mouth and looks away when he answers, swing your chair to point directly at him and say, ‘Are you sure about that?’ This simple movement exerts non-verbal pressure on him and can force him to tell the truth.

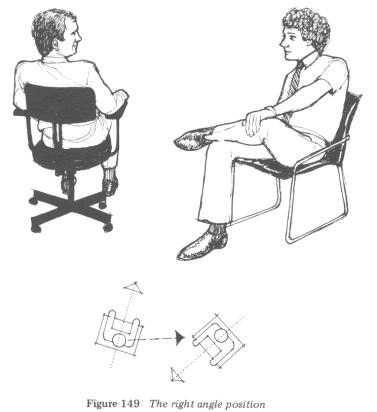

When you position your body at a right angle away from your subject, you take the pressure off the interview (Figure 149). This is an excellent position from which to ask delicate or embarrassing questions, encouraging more open answers to your questions without any pressure coming from you. If the nut you are trying to crack is a difficult one, you may need to revert to the direct body point technique to get to the facts.

Summary

If you want a person to have rapport with you, use the triangular position and, when you need to exert non-verbal pressure, use the direct body point. The right angle position allows the other person to think and act independently, without non-verbal pressure from you. Few people have ever considered the effect of body pointing in influencing the attitudes and the responses of others.

These techniques take much practice to master but they can become ‘natural’ movements before long. If you deal with others for a living, mastery of body point and swivel chair techniques are very useful skills to acquire. In your day-to-day encounters with others, foot pointing, body pointing and positive gesture clusters such as open arms, visible palms, leaning forward, head tilting and smiling can make it easy for others not only to enjoy your company, but to be influenced by your point of view.

Sixteen

Desks, Tables and Seating Arrangements

TABLE SEATING POSITIONS

Strategic positioning in relation to other people is an effective way to obtain cooperation from them. Aspects of their attitude toward you can be revealed in the position they take in relation to you.

Mark Knapp, in his book

Non-Verbal Communication in Human Interaction,

noted that, although there is a general formula for interpretation of seating positions, the environment may have an effect on the position chosen. Research conducted with white middle-class Americans showed that seating positions in the public bar of an hotel can vary from the seating positions taken in a high-class restaurant and that the direction in which the seats are facing and the distance between tables can have a distorting influence on seating behaviour. For example, intimate couples prefer to sit side by side wherever possible, but in a crowded restaurant where the tables are close together this is not possible and the couples are forced to sit opposite each other in what is normally a defensive position.

Because of a wide range of moderating circumstances, the following examples relate primarily to seating arrangements in an office environment with a standard rectangular desk.

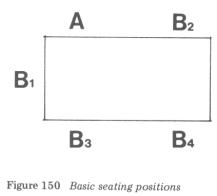

Person B can take four basic seating positions in relation to person A.

B1: The corner position

B2: The co-operative position

B3: The competitive-defensive position

B4: The independent position

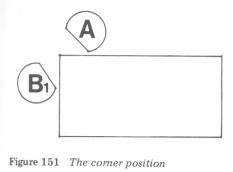

The Corner Position (B1)

This position is normally used by people who are engaged in friendly, casual conversation. The position allows for unlimited eye contact and the opportunity to use numerous gestures and to observe the gestures of the other person. The corner of the desk provides a partial barrier should one person begin to feel threatened, and this position avoids territorial division on the top of the table. The most successful strategic position from which a sales person can deliver a presentation to a new customer is by position B1 assuming A is the buyer. By simply moving the chair to position B1 you can relieve a tense atmosphere and increase the chances of a favourable negotiation.

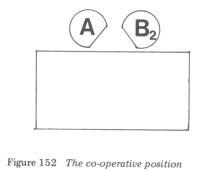

The Co-operative Position (B2)

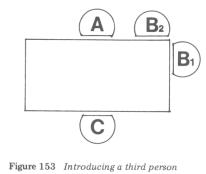

When two people are mutually oriented, that is, both thinking alike or working on a task together, this position usually occurs. It is one of the most strategic positions for presenting a case and having it accepted. The trick is, however, for B to be able to take this position without A feeling as though his territory has been invaded. This is also a highly successful position to take when a third party is introduced into the negotiation by B, the sales person. Say, for example, that a sales person was having a second interview with a client and the sales person introduced a technical expert. The following strategy would be most suitable.

The technical expert is seated at position C opposite customer A. The sales person can sit either at position B2 (co-operative) or B1 (corner). This allows the sales person to be ‘on the client’s side’ and to question the technician on behalf of the client. This position is often known as ‘siding with the opposition’.

The Competitive-Defensive Position (B3)

Sitting across the table from a person can create a defensive, competitive atmosphere and can lead to each party taking a firm stand on his point of view because the table becomes a solid barrier between both parties. This position is taken by people who are either competing with each other or if one is reprimanding the other. It can also establish that a superior/subordinate role exists when it is used in A’s office.

Argyle noted that an experiment conducted in a doctor’s office showed that the presence or absence of a desk had a significant effect on whether a patient was at ease or not. Only 10 per cent of the patients were perceived to be at ease when the doctor’s desk was present and the doctor sat behind it. This figure increased to 55 per cent when the desk was absent.

If B is seeking to persuade A, the competitive-defensive position reduces the chance of a successful negotiation unless B is deliberately sitting opposite as part of a pre-planned strategy. For example, it may be that A is a manager who must severely reprimand employee B, and the competitive position can strengthen the reprimand. On the other hand, it may be necessary for B to make A feel superior and so B deliberately sits directly opposite A.

Whatever line of business you are in, if it involves dealing with people, you are in the influencing business and your objective should always be to see the other person’s point of view, to put him or her at ease and make him or her feel right about dealing with you; the competitive position does not lead towards this end. More co-operation will be gained from the corner and co-operative positions than will ever be achieved from the competitive position. Conversations are shorter and more specific in this position than from any other.

Whenever people sit directly opposite each other across a table, they unconsciously divide it into two equal territories. Each claims half as his own territory and will reject the other’s encroaching upon it. Two people seated competitively at a restaurant table will mark their territorial boundaries with the salt, pepper, sugar bowl and napkins.

Here is a simple test that you can conduct at a restaurant which demonstrates how a person will react to invasion of his territory. I recently took a salesman to lunch to offer him a contract with our company. We sat at a small rectangular restaurant table which was too small to allow me to take the comer position so I was forced to sit in the competitive position.

The usual dining items were on the table: ashtray, salt and pepper shakers, napkins and a menu. I picked up the menu, read it, and then pushed it across into the other man’s territory. He picked it up, read it, and then placed it back in the centre of the table to his right. I then picked it up again, read it, and placed it back in his territory. He had been leaning forward at this point and this subtle invasion made him sit back. The ashtray was in the middle of the table and, as I ashed my cigarette, I pushed it into his territory. He then ashed his own cigarette and pushed the ashtray back to the centre of the table once again. Again, quite casually, I ashed my cigarette and pushed the ashtray back to his side. I then slowly pushed the sugar bowl from the middle to his side and he began to show discomfort. Then I pushed the salt and pepper shakers across the centre line. By this time, he was squirming around in his seat as though he was sitting on an ant’s nest and a light film of sweat began to form on his brow. When I pushed the napkins across to his side it was all too much and he excused himself and went to the toilet. On his return, I also excused myself. When I returned to the table I found that all the table items had been pushed back to the centre line!

This simple, effective game demonstrates the tremendous resistance that a person has to the invasion of his territory. It should now be obvious why the competitive seating arrangement should be avoided in any negotiation or discussion.

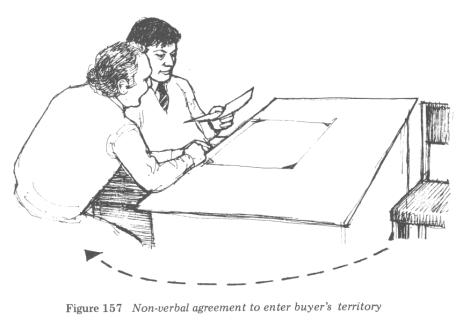

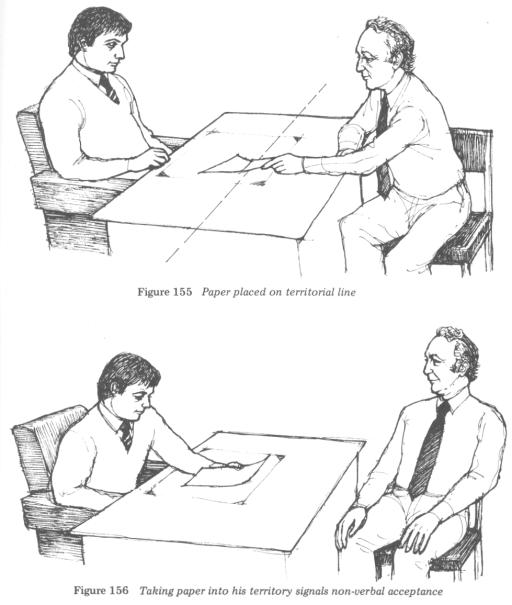

There will be occasions on which it may be difficult or inappropriate to take the corner position to present your case. Let us assume that you have a visual presentation; a book, quotation or sample to present to another person who is sitting behind a rectangular desk. First, place the article on the table (Figure 155). The other person will lean forward and look at it, take it into his territory or push it back into your territory.

If he leans forward to look at it, you must deliver your presentation from where you sit as this action non-verbally tells you that he does not want you on his side of the desk. If he takes it into his territory this gives you the opportunity to ask permission to enter his territory and take either the corner or cooperative positions (Figure 157). If, however, he pushes it back, you’re in trouble! The golden rule is never to encroach on the other person’s territory unless you have been given verbal or non-verbal permission to do so or you will put them offside.