Born on a Blue Day: Inside the Extraordinary Mind of an Autistic Savant (8 page)

Read Born on a Blue Day: Inside the Extraordinary Mind of an Autistic Savant Online

Authors: Daniel Tammet

Another story that really affected me was ‘Stone Soup’. In it, a wandering soldier arrives in a village asking for food and shelter. The villagers, greedy and fearful, provide none, so the soldier declares that he will make them stone soup with nothing required but a cauldron, water and a stone. The villagers huddle round as the soldier begins to cook his dish, licking his lips in anticipation. ‘Of course, stone soup with cabbage is hard to beat,’ says the soldier to himself in a loud voice. One of the villagers approaches and puts one of his cabbages into the pot. Then the soldier says: ‘Once I had stone soup with cabbage and a bit of salt beef and it was fit for a king!’ Sure enough, the village butcher brings some salt beef and one by one the other villagers provide potatoes, onions, carrots, mushrooms, and so on until a delicious meal is ready for the entire village. I found the story very puzzling at the time because I had no concept of deception and did not understand that the soldier was pretending to make a soup from a stone in order to trick the villagers into contributing to it. Only many years later did I finally understand what the story was about.

But some fantasy was just too frightening for me. Once a week a television was wheeled into the classroom and an educational programme played.

Look and Read

was a popular BBC children’s television series and one of its most watched programmes was

Dark Towers

involving a young girl who, alongside her dog, race to find the hidden treasure of a strange, old house called Dark Towers. The series was played over ten weeks.

In its first episode, the young girl – Tracy – discovers Dark Towers and learns that it is supposed to be haunted. At the end of the episode a family portrait begins to shake and the room goes very cold. Tracy hears a voice telling her that the house is in danger and she will help to save it. I remember watching the programme with the rest of the class in silence, my legs together rocking quietly under the chair. I felt no emotion at all until the end, then all of a sudden it was like a switch was flicked in my head and I suddenly realised I was frightened. Feeling agitated I ran from the class – refusing to return until the television was removed. Thinking back, I can understand why the other children teased me and called me ‘cry baby’. I was nearly seven and none of the other children in the class were the slightest bit upset or frightened by the programme. Even so, each week I was taken to the headmaster’s office and allowed to sit and wait while the rest of the class watched the next instalment of the series. The headmaster had a small television in his office and I remember watching motor racing on it – the cars were going very fast round and round and round the circuit; this, at least, was a programme I could watch.

Another

Look and Read

series that I remember affected me very much was called

Through the Dragon’s Eye

. In it, three children walk through a mural they have painted on the playground wall and into a strange land called Pelamar. The land is dying and the children seek to mend its life force, a glowing, hexagonal structure that has been thrown apart in an explosion. With the help of a friendly dragon called Gorwen, the children search the land for the missing parts.

This time there were no tantrums. For one thing I was older, ten, but the programme itself was what fascinated me. It was beautifully visual, the children surrounded by various richly coloured landscapes as they made their way across the magical land. Several of the series’ characters – keepers of the life force – were painted from head to toe in bright colours of purple, orange and green. Then there was the huge talking mouse and the giant caterpillar. In one scene, snow-flakes fall from the air and are caught in the children’s hands, magically transforming into letters which form words (a clue to help the children find one of the missing life force pieces). In another, stars in the night sky light up into shining road signs for the flying dragon Gorwen. Scenes like these fascinated me because the story was told primarily in pictures, which I could relate to best, rather than spoken dialogue.

Watching the television at home became a regular part of my after-school routine. My mother recalls that I always sat very close to the set and became upset if she tried to make me move back a little to protect my eyes. Even in hot weather I always kept my coat on after coming home from school and wore it all the time that I was watching the different programmes, sometimes even longer. I thought of it as an extra protective layer against the outside world, like a knight and his suit of armour.

Meanwhile, the family was growing. My parents were not at all religious, they simply loved children, and always wanted to have a large family. A sister, Claire, was born in the month that I began school, followed two years later by the arrival of my second brother Steven. Shortly afterwards my mother discovered she was pregnant again with her fifth child, my brother Paul, and it became necessary for us to move to a larger house. I had little reaction at first to the growing band of siblings, sitting and playing by myself in the quiet of my bedroom while my brothers and sister shouted and played and ran around downstairs and in the garden. Their presence did ultimately have a very positive influence on me, however: it forced me to gradually develop my social skills. Having people constantly around me helped me to cope better with noise and change. I also began to learn how to interact with other children by silently watching my siblings playing with each other and their friends from my bedroom window.

We moved in the middle of 1987 to Hedingham Road, number forty-three. Interestingly, all three of my childhood addresses were prime numbers: 5, 43, 181. Even better, each of our next-door neighbours had primes on their front doors too: 3 (and 7), 41, 179. Such number pairs are called ‘twin primes’ – prime numbers that differ by two. Twin primes become rarer the higher you count, so for example finding prime number neighbours with door numbers starting with ‘9’ would require a very long street indeed; the first such pair is 9,011 and 9,013.

The year of our move was also marked by rare severe weather. January saw some of the coldest weather in southern England for over a hundred years, with temperatures falling to minus nine degrees in some places. The cold brought heavy snowfall and days off school. Outside the children were throwing snowballs and being pulled along on sleds, but I was content to sit at my window and watch the snowflakes falling and fluttering from the sky. Later, when everyone else had gone indoors, I ventured out alone and piled the snow in the front garden into identical pillars several feet high. Looking down from my bedroom they formed a circle – my favourite shape. A neighbour came over to the house and said to my parents: ‘Your son has made Stonehenge in the snow.’

1987 was also the year of the great October storm – the worst to affect the south east of England since 1703. Winds reached 100mph in places and eighteen people died as a result of the storm damage. That night I went to bed but found it hard to sleep. My parents had recently bought me a new pair of pyjamas, but the fabric was itchy and I kept turning in bed. I woke to a breaking sound – tiles were being ripped from the roof by the wind and thrown down onto the street below. I climbed onto the windowsill and looked out: everywhere was pitch black. It was warm, too, unusually for the time of year, and my hands were sweaty and stuck to the sill as I pulled myself off. Then I heard a creaking noise coming towards my room. The door opened and in came a trembling, orange light atop a thick, long white candle. I stared at it until a voice, my mother’s, asked me if I was all right. I did not say anything because she was holding the candle out in front of her and I wondered whether she was giving it to me, like the bright red candle on a cake she had given me for my last birthday, but I didn’t want it because it wasn’t my birthday yet.

‘Do you want some hot milk?’

I nodded and followed her slowly downstairs to the kitchen. It was dark everywhere, because the power had been cut and none of the light switches worked. I sat up at the table with my mother and drank the frothy milk she had prepared and poured into my favourite mug – it was patterned all over with coloured dots and I used it for every drink. After being led back upstairs to my room I climbed into bed, pulled the covers over my head and fell back to sleep.

In the morning I was woken by my father and told there would be no school that day. Looking out of my bedroom window, I could see broken roof tiles and dustbin lids scattered over the street and people talking in small groups and shaking their heads.

Downstairs, the family was crowded in the kitchen looking out on the garden at the back of the house. The large tree at the bottom of the garden had been ripped out of the ground by the storm’s winds, its branches and roots splayed across the grass. It was several weeks before the tree could be sawn up and removed. In the interim I spent many happy hours alone climbing around the tree trunk and hiding among its branches, invariably returning indoors covered in dirt, bugs and scratches.

The house in Hedingham Road was just across the street from my school. I could see the teachers’ car park from my bedroom window, which made me feel safe. Every day after school I would run to my bedroom to watch the cars drive away. I counted them one by one as they left, and remembered each number plate. Only once the last cars had gone did I climb down and go downstairs for supper.

My most vivid memory of that house is of washed nappies drying on the fire and of babies on my parents’ laps crying for milk. A year after the move my mother gave birth for the sixth time, to twins. Maria and Natasha were a welcome addition to the family for my mother, who with four sons and only one daughter until then had been very much hoping for girls to help even out the gender ratio. When my mother came back from the hospital she called me downstairs from my room to see my new baby sisters. It was July – the height of summer – and I could tell she was hot because some of the hairs at the front of her brow were stuck to her forehead. My father told me to sit down on the settee in the living room and to keep my back straight. Then, slowly, he collected the babies in his arms and brought them over to me and placed them carefully so that I held one in each arm. I looked down at them; they had fat cheeks and tiny fingers and were dressed in matching pink tops with little plastic buttons. One of the buttons was undone, so I did it up.

The size of our family brought its own set of challenges. Bathtime was always a rushed and crowded affair. Every Sunday evening at six o’clock my father would roll up his sleeves and call the boys (myself and my brothers Lee, Steven and Paul) to the bathroom for our weekly ablutions. I hated bathtime: having to share the bath with my brothers, having hot soapy water poured from a jug over my hair and face, my brothers splashing each other, the heat of the steam that filled the room. I often cried but my parents insisted that I bathe with the others. With so many people in one house, hot water was at a premium.

So, too, was money. With five children under the age of four, my parents both stayed at home to help raise the family. The absence of a wage-earner put a lot of pressure on my mother and my father; arguments over what and where and when to spend became more and more common. Even so, my parents did everything they could to ensure we children were never without such things as food, clothes, books or toys. My mother made bargain hunting in the local charity and secondhand shops and markets into an art, while my father proved himself very handy around the house. Together they made a formidable team.

I stayed away as much as I could manage from the daily hubbub; the bedroom I shared with my brother Lee was where my family knew to find me, no matter what the time of day. Even in summer, when my brothers and sisters were running around together in the sunshine outside, I remained seated on the floor in my room with my legs crossed and my hands in my lap. The carpet was thick and lumpy and clay-red; I often rubbed the back of my hands against its surface because I liked the feel of its texture on my skin. During warm weather the sunlight poured into my room, brightly tingeing the many specks of dust swimming in the air around me as they merged into a single pattern of freckled light. As I sat still and silent for hour after hour, I diligently watched the wash of different hues and colours ebb and flow across the walls and furniture of my room with the day’s passage; the flow of time made visual.

Knowing my obsession with numbers, my mother gave me a book of mathematical puzzles for children that she had spotted in a second-hand shop. I remember this was around the time I started primary school, because Mr Thraves – my teacher – told me off if I brought the book into class with me. He thought I spent too much time thinking about numbers and not enough time participating with the rest of the class, and of course he was right.

One of the exercises in the book read like this: There are twenty-seven people in a room and each shakes hands with everyone else. How many handshakes are there altogether?

When I read the exercise I closed my eyes and imagined two men inside a large bubble, then I imagined a half-bubble stuck to the side of the larger bubble with a third person inside it. The pair in the large bubble shook hands with each other, then each with the third man in the half-bubble. That meant three handshakes for three people. Then I imagined a second half-bubble stuck to the other side of the larger bubble with a fourth person in it. Then the pair in the large bubble needed to each shake hands with him too, and then the half-bubble men shake hands with each other. That would make six handshakes between four people. I continued in this way, imagining two more men in two other half-bubbles, until there were six in all and fifteen handshakes between them. The sequence of handshakes looked like this:

1, 3, 6, 10, 15 …

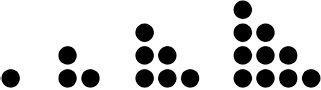

And I realised that they were triangular numbers. These are numbers that can be arranged to form a triangle when you represent them as a series of dots, like so: