Born on a Blue Day: Inside the Extraordinary Mind of an Autistic Savant (6 page)

Read Born on a Blue Day: Inside the Extraordinary Mind of an Autistic Savant Online

Authors: Daniel Tammet

The family’s accommodation consisted of two cramped, unfurnished rooms. No television or radios were allowed. In one room – the children’s – there was space for three small beds. My grandmother’s room had a bed, table and chair. No men were allowed to stay, so her husband was forced to rent rooms above a shop. They would be separated for the duration of the family’s stay at the hostel.

Life at the hostel was grim – apart from the bare accommodation, there was no privacy; doors were to remain unlocked at all times, and the staff were strict and ran the building in a military fashion. The family hated their time there, which lasted for a year and a half. Their stay was only brightened a little by the friendship my grandmother was able to strike up with the hostel manager, a Mrs Jones. Eventually, the family was moved to a new house.

My father met his father for the first time when he was eleven. By then my grandfather’s seizures were less frequent and he was allowed out on day release to work at his shoe repair shop. In the evenings he returned to the institution. My father had been very young when my grandfather’s illness began, so he had no memories of him and did not even know what he looked like. They met at the home of the family friend who had helped care for him and his stepsiblings several years earlier. My father remembers shaking hands with a grey-haired man with ill-fitting clothes who was then introduced to him as his father. Over time, they grew close.

As my grandfather got older his health quickly deteriorated. My father would visit him at the hospital as often as he could. He was twenty-one when my grandfather died, of organ failure following a stroke and seizure. From all accounts he was a kind and gentle man. I wish I could have had the opportunity to meet him.

I am extremely fortunate to live in an age of many important medical advances, so that my own experience of epilepsy was nothing like that of my grandfather’s. Following the seizures and my diagnosis, I think what must have frightened my parents most of all was the possibility that I would not be able to lead the ‘normal’ life they really wanted for me. Like many parents, they equated normality with being happy and productive.

The seizures did not recur – as is the case in around 80% of those living with epilepsy, my medication was effective which meant I lived seizure-free. I think this was the biggest factor in my mother’s ability to cope with my illness. She was very sensitive to the fact that somehow I had always been different, vulnerable, in need of extra care and support and love. Sometimes she got upset at the thought that I could have another seizure at any time. Then she would go into another room and cry softly. I remember my father telling me not to go into the room when my mother was upset.

I found it very hard to pick up on my mother’s feelings. It didn’t help that I remained in my own world, engrossed in the smallest things but unable to understand the various emotions or tensions at home. My parents sometimes fought, as I think most parents do, over their children and the best way to deal with different situations. When they argued, their voices turned a dark blue colour in my mind and I would crouch on the floor and press my forehead into the carpet with my hands over my ears until the noise abated.

It was my father who helped me to take my tablets every day, with a glass of milk or water around mealtimes. The medication – carbamazepine – meant I had to go with him to the hospital every month for blood tests, because of the effect the tablets can sometimes have on liver function. My father is a stickler for punctuality and we were always at the hospital waiting area at least an hour before the appointment was due. He would buy me a plastic cup of orange juice and some cookies while we waited. The chairs that we sat on were plastic and uncomfortable but I remember not wanting to stand up on my own, so I waited for my father to stand before I did. There were lots of chairs and I passed the time by counting them over and over.

When the nurse called my name, my father walked with me to a small curtained-off area where I sat down and the nurse rolled up one of my sleeves and dabbed the centre of my arm. I had many blood tests so that with time I knew what to expect. The nurse encouraged patients to look away while the needle was being inserted but I kept my head still, my gaze fixed, watching the transparent tube above the needle fill with dark red blood. Once she was finished, the nurse dabbed the arm clean and stuck cotton wool in place with a plaster that had a smiley face on it.

One of the commonest side effects of the medication is hypersensitivity to sunlight and I spent the summer months indoors while my brother played outside in the garden and the park. I didn’t mind because, even today, sunlight often makes me feel itchy and uncomfortable and I rarely venture outside for long periods in sunny weather. My parents wanted to supervise me even more closely following the seizures so I spent a lot of time in the living room, where my mother could keep a close eye on me, watching television or playing with coins or beads I was given to count with.

Feelings of dizziness or grogginess were also common side effects I experienced. Whenever I started to feel dizzy I would immediately sit down, cross my legs and wait for the sensation to pass. This sometimes caused embarrassment for my parents if they were walking with me in the street and I suddenly stopped and sat down in the middle of the pavement. Fortunately the dizzy spells did not last long, just a matter of seconds. The loss of control, as well as the unpredictability of the spells, frightened me and I was often tetchy and tearful following one.

There exists a complex relationship between sleep and epilepsy, with a higher incidence of sleep disorders found among those with the condition. Some scientists believe that sleep-related events such as sleep terrors and sleepwalking may actually represent nocturnal seizure activity in the brain. I occasionally sleepwalked – in some periods frequently, in others less – from around the age of six through to the start of my adolescence. Sleepwalking (somnambulism) occurs during the first three hours of sleep, when the sleeper’s brain waves have increased in size and the sleep is dreamless and deep. Typically, the sleepwalker does not respond if talked to and does not remember the episode upon waking. In my case, I would climb out of bed and walk repetitively in the same path around my room. Sometimes I would bang into the walls or door in my room, waking my parents who would gently guide me back to bed. Though it’s not in fact harmful to wake someone who is sleepwalking, it can be confusing and upsetting for the sleepwalker.

My parents took several precautions to ensure my safety during the night. They cleared the floor of my room of any toys each evening before bed and left a light on in the hallway when it came to bedtime. They also fitted a gate at the top of the stairs after one occasion when I apparently sleepwalked down the stairs and to the back of the house and was found pulling at the kitchen door leading out to the garden.

Perhaps not surprisingly, during the day it frequently felt like all my energy had been emptied away and all I wanted to do was sleep. It was normal for me to put my head down on my school desk in class and fall asleep. The teachers, fully informed by my parents, were always sympathetic and tolerant. It was often disorientating to wake up after a period of ten or twenty or thirty minutes and find the class empty and the children running outside in the playground, but my teacher was always there to reassure me.

The cumulative impact of the various side effects of my medication on my first year at school was considerable. I found it hard to concentrate in class, or to work at a consistent pace. I was the last child in the class to master my ABC. My teacher, Mrs Lemon, gave me extra encouragement with coloured stickers if I made fewer and fewer mistakes as I wrote the alphabet down. I never felt self-conscious or embarrassed at lagging behind the other children; they just weren’t a part of my world.

Twice a year I visited the Westminster Children’s Hospital in London with my father for a brain scan to monitor my condition. We would go by taxi, arrive early as usual, and then wait for the consultant to call us. I must have spent many, many hours over those years sitting in hospital waiting areas.

After three years the decision was made to gradually phase out my anti-seizure medication. My mother panicked at the thought that the epilepsy might return, though fortunately I remained and remain today seizure-free. The previous side effects of the medication disappeared and my performance at school improved thereafter.

It’s not clear what lasting effect – if any – the epilepsy has had on my brain and how it works. My childhood seizures originated in the left temporal lobe and some researchers suggest that one explanation for savant abilities is left brain injury leading to right brain compensation. This is because the skills most commonly seen in savants, including numbers and calculation, are associated with the right hemisphere.

However, it is not easy to determine whether the epilepsy is a cause or a symptom of the left brain injury and it is possible that my seizures in childhood came about as a consequence of pre-existing damage in the brain, probably there from birth.

For this reason, scientists have been interested in studying my perception abilities to see in what way they differ from those of other people. A study was carried out at the Autism Research Centre in Cambridge in the autumn of 2004. The centre’s director is Simon Baron-Cohen, a professor of developmental psycho-pathology and a leading researcher into autistic spectrum disorders.

The study tested the ‘weak central coherence’ theory, which says that individuals on the autistic spectrum are more likely to process details at the expense of global information (‘the bigger picture’), whereas most people integrate information into context and gist – often missing out on smaller details. For example, studies have shown that autistic children are better at recognising familiar faces in photographs when given just part of the face than are non-autistic controls.

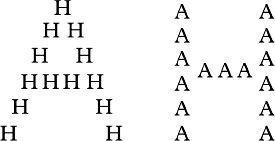

In the Navon task, participants are asked to identify a selected target occurring at either a local or global level. In my test at the centre, the scientists asked me to press a button by my left hand if I saw a letter ‘A’ and to press a button by my right hand if I didn’t. Images were flashed up onto a screen in front of me and responses were automatic. On several occasions I pressed ‘no’, only for my brain to catch up seconds later with the perception that the overall configuration of the letters created an ‘A’ shape. Scientists call this phenomenon ‘interference’ and it is commonly employed in optical illusions. For most people, the interference is caused by the global shape – for example, when presented with a letter ‘H’ composed of lots of small ‘A’s, most people will not immediately see the ‘A’s because of the interference effect of seeing the ‘H’ shape. In my case, like those of most people on the autistic spectrum, the interference is reversed and I struggle to see the overall letter shape because my brain focuses automatically on the individual details.

In the above illustrations the image on the left shows the letter ‘A’ composed of smaller ‘H’s. The right image shows the letter ‘H’ composed of smaller ‘A’s.

In Australia, Professor Allan Snyder – director of the Centre for the Mind at the University of Sydney – has attracted considerable interest for his claims that he can reproduce savant-like abilities in subjects using a technique called transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS).

TMS has been used as a medical tool in brain surgery, stimulating or suppressing particular areas of the brain to allow doctors to monitor the effects of surgery in real time. It is non-invasive and seemingly free of serious side effects.

Professor Snyder believes that autistic thought is not wholly different to ordinary thought, but an extreme form of it. By temporarily inhibiting some brain activity – the ability to think contextually and conceptually, for example – TMS, Professor Snyder argues, can be used to induce heightened access to parts of the brain responsible for collecting raw, unfiltered information. By doing this, he hopes to enhance the brain by shutting off certain parts of it, changing the way the subject perceives different things.

The professor uses a cap attached by electrodes to a TMS machine. The machine sends varying pulses of magnetic energy to the temporal lobes. Some of the subjects who have undergone the procedure claim temporarily enhanced drawing and proofreading skills; drawings of animals became more life-like and detailed, and reading became more precise.

Most people read by recognising familiar groupings of words. For this reason, many miss small errors of spelling or word repetition. Take the following example:

A bird in the hand

is worth two in the

the bush

Read quickly, most people don’t spot the second, superfluous ‘the’ in the sentence above.

A side benefit of processing information in parts instead of holistically is that having a good eye for detail, I proofread very well. On Sunday mornings, reading pages of the day’s newspaper at the table, I would annoy my parents no end by pointing out every grammatical and spelling error I found. ‘Why can’t you just read the paper like everyone else?’ my exasperated mother would ask, having listened to me point out the twelfth error in the paper.