Born on a Blue Day: Inside the Extraordinary Mind of an Autistic Savant (2 page)

Read Born on a Blue Day: Inside the Extraordinary Mind of an Autistic Savant Online

Authors: Daniel Tammet

I was born on 31 January 1979 – a Wednesday. I know it was a Wednesday, because the date is blue in my mind and Wednesdays are always blue, like the number nine or the sound of loud voices arguing. I like my birth date, because of the way I’m able to visualise most of the numbers in it as smooth and round shapes, similar to pebbles on a beach. That’s because they are prime numbers: 31, 19, 197, 97, 79 and 1979 are all divisible only by themselves and one. I can recognise every prime up to 9973 by their ‘pebble-like’ quality. It’s just the way my brain works.

I have a rare condition known as savant syndrome, little known before its portrayal by actor Dustin Hoffman in the Oscar-winning 1988 film

Rain Man

. Like Hoffman’s character, Raymond Babbitt, I have an almost obsessive need for order and routine, which affects virtually every aspect of my life. For example, I eat exactly 45 grams of porridge for breakfast each morning; I weigh the bowl with an electronic scale to make sure. Then I count the number of items of clothing I’m wearing before I leave my house. I get anxious if I can’t drink my cups of tea at the same time each day. Whenever I become too stressed and I can’t breathe properly, I close my eyes and count. Thinking of numbers helps me to become calm again.

Numbers are my friends and they are always around me. Each one is unique and has its own personality. Eleven is friendly and five is loud, whereas four is both shy and quiet – it’s my favourite number, perhaps because it reminds me of myself. Some are big – 23, 667, 1179 – while others are small: 6, 13, 581. Some are beautiful, like 333, and some are ugly, like 289. To me, every number is special.

No matter where I go or what I’m doing, numbers are never far from my thoughts. In an interview with chat show host David Letterman in New York, I told David he looked like the number 117 – tall and lanky. Later outside, in the appropriately numerically named Times Square, I gazed up at the towering skyscrapers and felt surrounded by nines – the number I most associate with feelings of immensity.

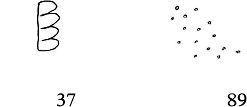

Scientists call my visual, emotional experience of numbers synaesthesia, a rare neurological mixing of the senses, which most commonly results in the ability to see alphabetical letters and/or numbers in colour. Mine is an unusual and complex type, through which I see numbers as shapes, colours, textures and motions. The number one, for example, is a brilliant and bright white, like someone shining a torch beam into my eyes. Five is a clap of thunder or the sound of waves crashing against rocks. Thirty-seven is lumpy like porridge, while eighty-nine reminds me of falling snow.

Probably the most famous case of synaesthesia was the one written up over a period of thirty years from the 1920s by the Russian psychologist A.R. Luria of a journalist called Shereshevsky who had a prodigious memory. ‘S’, as Luria called him in his notes for the book

The Mind of a Mnemonist

, had a highly visual memory which allowed him to ‘see’ words and numbers as different shapes and colours. ‘S’ was able to remember a matrix of 50 digits after studying it for three minutes, both immediately afterwards and many years later. Luria credited Shereshevsky’s synaesthetic experiences as the basis for his remarkable short- and long-term memory.

Using my own synaesthetic experiences since early childhood, I have grown up with the ability to handle and calculate huge numbers in my head without any conscious effort, just like the Raymond Babbitt character. In fact, this is a talent common to several other real-life savants (sometimes referred to as ‘lightning calculators’). Dr Darold Treffert, a Wisconsin physician and the leading researcher in the study of savant syndrome, gives one example, of a blind man with ‘a faculty of calculating to a degree little short of marvellous’ in his book

Extraordinary People

:

When he was asked how many grains of corn there would be in any one of 64 boxes, with 1 in the first, 2 in the second, 4 in the third, 8 in the fourth, and so on, he gave answers for the fourteenth (8,192), for the eighteenth (131,072) and the twenty-fourth (8,388,608) instantaneously, and he gave the figures for the forty-eighth box (140,737,488,355,328) in six seconds. He also gave the total in all 64 boxes correctly (18,446,744,073,709,551,616) in forty-five seconds.

My favourite kind of calculation is power multiplication, which means multiplying a number by itself a specified number of times. Multiplying a number by itself is called squaring; for example, the square of 72 is 72 × 72 = 5,184. Squares are always symmetrical shapes in my mind, which makes them especially beautiful to me. Multiplying the same number three times over is called cubing or ‘raising’ to the third power. The cube or third power of 51 is equivalent to 51 × 51 × 51 = 132,651. I see each result of a power multiplication as a distinctive visual pattern in my head. As the sums and their results grow, so the mental shapes and colours I experience become increasingly more complex. I see thirty-seven’s fifth power – 37 × 37 × 37 × 37 × 37 = 69,343,957 – as a large circle composed of smaller circles running clockwise from the top round.

When I divide one number by another, in my head I see a spiral rotating downwards in larger and larger loops, which seem to warp and curve. Different divisions produce different sizes of spirals with varying curves. From my mental imagery I’m able to calculate a sum like 13 ÷ 97 (0.1340206 …) to almost a hundred decimal places.

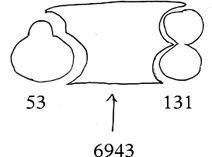

I never write anything down when I’m calculating, because I’ve always been able to do the sums in my head and it’s much easier for me to visualise the answer using my synaesthetic shapes than to try to follow the ‘carry the one’ techniques taught in the textbooks we are given at school. When multiplying, I see the two numbers as distinct shapes. The image changes and a third shape emerges – the correct answer. The process takes a matter of seconds and happens spontaneously. It’s like doing maths without having to think.

In the illustration above I’m multiplying 53 by 131. I see both numbers as a unique shape and locate each spatially opposite the other. The space created between the two shapes creates a third, which I perceive as a new number: 6,943, the solution to the sum.

Different tasks involve different shapes and I also have various sensations or emotions for certain numbers. Whenever I multiply with eleven I always experience a feeling of the digits tumbling downwards in my head. I find sixes hardest to remember of all the numbers, because I experience them as tiny black dots, without any distinctive shape or texture. I would describe them as like little gaps or holes. I have visual and sometimes emotional responses to every number up to 10,000, like having my own visual, numerical vocabulary. And just like a poet’s choice of words, I find some combinations of numbers more beautiful than others: ones go well with darker numbers like eights and nines, but not so well with sixes. A telephone number with the sequence 189 is much more beautiful to me than one with a sequence like 116.

This aesthetic dimension to my synaesthesia is something that has its ups and downs. If I see a number I experience as particularly beautiful on a shop sign or a car number plate, there’s a shiver of excitement and pleasure. On the other hand, if the numbers don’t match my experience of them, if for example a shop sign’s price has ‘99p’ in red or green (instead of blue), then I find that uncomfortable and irritating.

It is not known how many savants have synaesthetic experiences to help them in the areas they excel in. One reason for this is that, like Raymond Babbitt, many suffer profound mental and/or physical disability, preventing them from explaining to others how they do the things that they do. I am fortunate not to suffer from any of the most severe impairments that often come with abilities such as mine.

Like most individuals with savant syndrome, I am also on the autistic spectrum. I have Asperger’s syndrome, a relatively mild and high-functioning form of autism that affects around 1 in every 300 people in the UK. According to a 2001 study by the UK’s National Autistic Society, nearly half of all adults with Asperger’s syndrome are not diagnosed until after the age of sixteen. I was finally diagnosed at age twenty-five following tests and an interview at the Autism Research Centre in Cambridge.

Autism, including Asperger’s syndrome, is defined by the presence of impairments affecting social interaction, communication and imagination (problems with abstract or flexible thought and empathy, for example). Diagnosis is not easy and cannot be made by a blood test or brain scan; doctors have to observe behaviour and study the individual’s developmental history from infancy.

People with Asperger’s often have good language skills and are able to lead relatively normal lives. Many have above-average IQs and excel in areas that involve logical or visual thinking. Like other forms of autism, Asperger’s is a condition affecting many more men than women (around 80% of autistics and 90% of those diagnosed with Asperger’s are men). Single-mindedness is a defining characteristic, as is a strong drive to analyse detail and identify rules and patterns in systems. Specialised skills involving memory, numbers and mathematics are common. It is not known for certain what causes someone to have Asperger’s, though it is something you are born with.

For as long as I can remember, I have experienced numbers in the visual, synaesthetic way that I do. Numbers are my first language, one I often think and feel in. Emotions can be hard for me to understand or know how to react to, so I often use numbers to help me. If a friend says they feel sad or depressed, I picture myself sitting in the dark hollowness of number six to help me experience the same sort of feeling and understand it. If I read in an article that a person felt intimidated by something, I imagine myself standing next to the number nine. Whenever someone describes visiting a beautiful place, I recall my numerical landscapes and how happy they make me feel inside. By doing this, numbers actually help me get closer to understanding other people.

Sometimes people I meet for the first time remind me of a particular number and this helps me to be comfortable around them. They might be very tall and remind me of the number nine, or round and remind me of the number three. If I feel unhappy or anxious or in a situation I have no previous experience of (when I’m much more likely to feel stressed and uncomfortable), I count to myself. When I count, the numbers form pictures and patterns in my mind that are consistent and reassuring to me. Then I can relax and interact with whatever situation I’m in.

Thinking of calendars always makes me feel good, all those numbers and patterns in one place. Different days of the week elicit different colours and emotions in my head: Tuesdays are a warm colour while Thursdays are fuzzy. Calendrical calculation – the ability to tell what day of the week a particular date fell or will fall on – is common to many savants. I think this is probably due to the fact that the numbers in calendars are predictable and form patterns between the different days and months. For example, the thirteenth day in a month is always two days before whatever day the first falls on, while several of the months mimic the behaviour of others, like January and October, September and December and February and March (the first day of January is the same as the first day of October). So if the first of January is a fuzzy texture in my mind (Thursday) for a given year, the thirteenth of October will be a warm colour (Tuesday).

In his book

The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat

, writer and neurologist Oliver Sacks mentions the case of severely autistic twins John and Michael as an example of how far some savants are able to take calendrical calculations. Though unable to care for themselves (they had been in various institutions since the age of seven), the twins were capable of calculating the day of the week for any date over a 40,000-year span.

Sacks also describes John and Michael playing a game for hours at a time that involved swapping prime numbers with each other. Like the twins, I have always been fascinated by prime numbers. I see each prime as a smooth textured shape, distinct from composite numbers (non-primes) that are grittier and less distinctive. Whenever I identify a number as prime, I get a rush of feeling in my head (in the front centre) which is hard to put into words. It’s a special feeling, like the sudden sensation of pins and needles.