Born on a Blue Day: Inside the Extraordinary Mind of an Autistic Savant (9 page)

Read Born on a Blue Day: Inside the Extraordinary Mind of an Autistic Savant Online

Authors: Daniel Tammet

Triangular numbers are formed like this: 1+2+3+4+5 … where 1+2 = 3 and 1+2+3 = 6 and 1+2+3+4 = 10 etc. You might notice that two consecutive triangular numbers make a square number e.g. 6+10 = 16 (4 × 4) and 10+15 = 25 (5 × 5). To see this, visually rotate the six so that it fits into the top right corner above the ten.

Having realised that the answer to the handshakes puzzle was a triangular number, I spotted a pattern that would help me to workout the solution. First of all I knew that the first triangular number – one – starts at two people, the fewest needed for one handshake. If the sequence of triangular numbers starts at two people, then the twenty-sixth number in the sequence would coincide with the number of handshakes generated by twenty-seven people shaking hands with each other.

Then I saw that ten, the fourth number in the sequence, has the relationship with four: 4+1 × 4/2, and this held for all the numbers in the sequence; for example fifteen, the fifth triangular number, = 5 + 1 × 5/2. So the answer to the puzzle is equivalent to 26+1 × 26/2 = 27 × 13 = 351 handshakes.

I loved doing these puzzles; they stretched me in a way that the maths I was taught in school did not. I spent hours at a time reading and working through the questions, whether in class, the playground or my room at home. Within its pages I found a sense of both calm and pleasure and for a while the book and I became inseparable.

One of the greatest sources of frustration for my parents was my obsessive collecting of different things, such as the shiny, brown conkers that fell in autumn in large quantities from huge trees that dotted a long road near our house. Trees were a source of fascination for me from as far back as I could remember; I loved rubbing the palms of my hands into the coarse, wrinkled bark and pressing the tips of my fingers along its furrows. The falling leaves formed spirals in the air, like the spirals I saw when I did divisions in my head.

My parents didn’t like me to go out on my own, so I collected the conkers with my brother Lee. I didn’t mind – he was an extra pair of hands. I scooped each conker up from the ground in my fingers and pressed its smooth, round shape into the hollow of my palm (a habit I have to this day – the tactile sensation acts as a kind of comforter, though nowadays I use coins or marbles). I stuffed my pockets one by one with the conkers until each was bulging full. It was like a compulsion, I just had to collect every conker I could see and put them all together in one place. I pulled my shoes and socks off and filled them with conkers too, walking barefoot back to the house with my hands and arms and pockets crammed full to overflowing.

Back at the house, I poured the conkers out onto the floor in my room and counted them over and over. My father came up with a plastic bin bag and made me count them into it. I spent hours each day collecting the conkers and bringing them back to my room and the rapidly filling sack in the corner. Eventually my parents, fearful that the weight of amassed conkers might damage the ceiling of the room below mine, took the sack out to the garden. They indulged my obsession, allowing me to continue to play with them in the garden, but I was not to bring them into the house in case I left any on the floor for my baby sisters to choke on. As the months went by, my interest eventually waned and the conkers became mouldy, until finally my parents arranged for them to be taken away to the local tip.

A short time afterwards came an obsessive interest in collecting leaflets, of all different sizes. They were frequently pushed through our letterbox with the local newspaper or the morning’s post and I was fascinated by their shiny feel and symmetrical shape (it didn’t matter what was being advertised – the text was of no interest to me). My parents were quick to complain of the precariously stacked piles that accumulated in every drawer and on every cupboard shelf in the house, especially as they poured out onto the floor every time a cupboard door was opened. As with the conkers, my leaflet mania gradually faded over time, much to my parents’ relief.

When my behaviour was good I was rewarded with pocket money. For example, if there were leaflets on the floor I was asked to pick them up and put them back in the drawer. In return, my parents gave me small value coins, lots of them, because they knew how much I loved circles. I spent hours painstakingly stacking the coins, one atop another, until they resembled shining, trembling towers each up to several feet in height. My mother always asked for lots of small change at the shops she went to, so that I always had a ready supply of coins for my towers. Sometimes I would build several piles of equal height around me in the shape of a circle and sit in the middle, surrounded on all sides by them, feeling calm and secure inside.

When the Olympic Games came to Seoul in South Korea in September 1988, the many different sights and sounds on the television screen, unlike anything I had seen before, riveted me. With 8,465 participants from 159 countries it was the largest games in history. There were so many extraordinary visuals: of the swimmers pulling at the glistening, foamy water, their goggled heads bobbing rhythmically up and down with every stroke; the sprinters racing down the lanes, their brown, sinewy arms and legs reduced to a blur; gymnasts springing and twisting and somersaulting in the air. I was engrossed by the television Olympic coverage and watched it as much as I could from the living room, no matter the sport or event.

It was a piece of good fortune when my teacher asked the class to write out an assignment based on the Games in Seoul. I spent the next week cutting and gluing hundreds of photos of the athletes and events from newspapers and magazines onto coloured cardboard sheets, my father helping me with the scissors. The choice of how to organise the different cuttings was made by a logic that was entirely visual: athletes dressed in red were pasted onto one sheet, those in yellow were put on another, those in white on a third, and so on. On smaller sheets of lined paper I wrote out in my best handwriting a long list of the names of all the countries I found mentioned in the newspapers with participants in the Games. I also wrote a list of all the different events, including Taekwondo – Korea’s national sport – and table tennis, which made its Olympic debut in Seoul. There were also lists of statistics and scores, including event points, race times, records broken and medals won. In the end, there were so many sheets of cuttings and written pages that my father had to hole-punch each one and tie them together with string. On the front cover I drew a picture of the Olympic rings in their colours of blue, yellow, black, green and red. My teacher gave me top marks for the amount of time and effort I had put into the project.

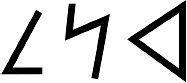

Reading about the many different countries represented at the Olympic Games made me want to learn more about them. I remember borrowing one book from the library that was about different languages from around the world. Inside was a description and illustration of the ancient Phoenician alphabet. It dates from around 1000

BC

and is thought to have led to the formation of many of the alphabet systems of the modern world, including Hebrew, Arabic, Greek and Cyrillic. Like Arabic and Hebrew, Phoenician is a consonantal alphabet, containing no symbols for vowel sounds; these had to be deduced from context. Whole words were usually written from right to left. I was fascinated by the distinctive lines and curves of the different letters and even began filling notepad after notepad with long sentences and stories exclusively in the Phoenician script. Using coloured pieces of chalk, I covered the inside walls of our garden shed with my favourite words composed entirely of the Phoenician letters. Below is my name, ‘Daniel’, in Phoenician:

The following year, when I was ten, an elderly neighbour died and a young family moved into the street. One day my mother answered the door to a small girl with blonde hair, who said she had seen a little girl from our house playing outside (that girl was my sister Claire) and asked whether she could come and play with her. My mother introduced her to my sister and me – she thought it a good opportunity for me to mix with other children in the neighbourhood – and we went over to her house and sat in the porch in her front garden. My sister and the little girl soon became good friends and played together most days in her garden. Her name was Heidi and she was around six or seven. Her mother was Finnish, but her father was from Scotland so Heidi had been raised speaking English and was only now beginning to learn her first Finnish words.

Heidi had several children’s books with brightly coloured drawings and the word for the object in Finnish under each. Beneath the drawing of a shiny, red apple was the word

omena

and under another of a shoe appeared the word

kenkä

. Something about the shape and sound of the Finnish words I read and heard was beautiful to me. While my sister and Heidi played together I sat and studied the books, learning the many words. Although they were very different from English words I was able to learn them very quickly and remember them all easily. Whenever I left Heidi’s garden I would always turn and say to her,

Hei Hei!

– the Finnish word for ‘goodbye!’

That summer I was allowed to walk the short distance to and from school by myself for the first time. The route was lined with row after row of hedges and one afternoon while walking home from class I noticed a tiny, red insect covered in black dots crawling inside one of the hedges. I was fascinated by it, so sat down on the pavement and watched it closely as it climbed over and under the sides of each small leaf and branch, stopping and starting and stopping again at various points along its journey. Its small back was round and shiny and I counted its dots over and over. Passers-by on the street stepped round me, some of them muttering under their breath. I must have been in their way, but at the time I did not think of anything but the ladybird in front of me. Carefully, I put out my finger for it to climb onto, then I ran for home.

I had only previously seen ladybirds in pictures in books, but had read all about them and knew, for example, that they are considered lucky in many cultures because they devour pests (they can eat as many as fifty to sixty aphids in a day) and help protect crops. In mediaeval times, farmers considered their help divine and it’s for this reason that they are named after the Virgin Mary. The ladybird’s black spots absorb energy from the sun, while its colours help to frighten away potential predators because most of them associate bright colours with poison. They also produce a chemical that tastes and smells horrible so predators won’t eat them.

I was very excited by my find and wanted to collect as many ladybirds as I could. My mother saw the little insect in my hand as I came through the front door and told me they were ‘clingy’ and that I should say, ‘ladybird, ladybird, fly away home!’, but I didn’t say it because I didn’t want it to fly away. Upstairs in my room was a plastic tub where I kept my collection of coins. I emptied it, pouring the coins into a mound on the floor, then took the tub and placed the ladybird inside it. Then I went back outside onto the street and spent several hours, until it got too dark to see anymore, looking inside the hedges for other ladybirds. As I found each one, I gently picked it up with my fingertips and placed it with the others in the tub. I had read that ladybirds liked leaves and aphids, so I pulled lots of leaves and some nettles which had aphids on them from the hedges and placed them in the tub with the ladybirds.

When I returned home I took the tub back up to my room and put it on the table next to my bed. I used a needle to pick some holes in the sides of the tub so the ladybirds would have plenty of air and light in their new home, then put a large book over the top of the tub, to prevent them from flying away all over the house. For the next week each day after school I went out and picked more leaves and aphids for the ladybirds and took them back to the tub in my room. I sprayed some of the leaves with water so they wouldn’t get thirsty.

In class I talked about the ladybirds ceaselessly until my exasperated teacher, Mr Thraves, asked me to bring them in. The next day I took the tub with me to school and showed my ladybird collection to him and the other children in the class. By that time I had found and placed hundreds of ladybirds in the one tub. He took one look and then asked me to put the tub down on his desk. He gave me a folded piece of paper and asked me to take it to the teacher in the next class. I was gone a few minutes. On my return the tub had disappeared. Mr Thraves, worried that the ladybirds might escape from the tub and fly all over his classroom, had told one of the other children to take it outside and release all the ladybirds. When I realised what had happened, my head felt like it was going to explode. I burst into tears and ran from the class all the way home. I was absolutely distraught and didn’t say a word to the teacher for weeks afterwards and became agitated if he even called my name.