Catastrophe 1914: Europe Goes to War (50 page)

Read Catastrophe 1914: Europe Goes to War Online

Authors: Max Hastings

Tags: #Ebook Club, #Chart, #Special

In the East Prussian border village of Popowen, south of Lyck, in the first days of August fearful peasants saw flames creeping rapidly closer, as neighbouring communities were torched. One day they glimpsed a lone Russian horseman looking down on them from a nearby hillside, rifle poised. He was soon followed by a troop of his comrades who departed after cutting the telegraph wire. Nobody could decide what to do for the best. Schoolteacher Johann Sczuka fled with his family and a cartload of possessions, only to return a few days later when all still seemed normal, save for thirsty and unmilked cows lowing on abandoned farms.

Back home, the Sczukas’ two young daughters were dispatched to scour the area for stray chickens and any other source of food. On their wanderings, the children chanced upon a man cycling from another village. As he spoke to them, they suddenly saw distant figures descending in their direction from the hills. The cyclist urged the girls to make themselves scarce. He himself rashly lingered, only to be shot down a few moments later, to the horror of the young spectators. The newcomers were Russians. The children dashed for home, heedless of nettles that stung their legs and rough ground on which ten-year-old Elisabeth lost her shoes. Exhausted, they took refuge in the family house and awaited the next act.

Through the days that followed, between 10 and 15 August, patrols of both armies drifted through the area. Local people warned a German cavalry troop that there were Russians in a nearby wood, but the men advanced anyway – and were fired upon. Dashing cavaliers learnt harsh lessons. Capt. Lazarev, a squadron commander of the Sumskoi Hussars, found his men reluctant to advance in the face of German fire. Seeking to inspire them by example, he galloped headlong towards the enemy – and was promptly shot out of his saddle. Another Russian officer expressed amazement at how quickly one adjusted to the horrors of war, especially

the corpses. They rotted fast in the summer heat, skin darkening, mouths gaping and teeth gleaming so that they were readily visible at a distance. ‘But it is only the first impression that is ghastly,’ he said. ‘After that, one becomes almost indifferent.’

The Sumskoi Hussars dismounted to approach a German position, then were crestfallen to find themselves almost horseless: their mounts, terrified by artillery fire, broke free from their pickets and bolted. Many men were obliged to plod ignominiously towards the rear on foot, though one who still had his horse carried a wounded cornet slung across the saddle. A mile back the soldiers were relieved to meet their commanding officer, who had recaptured most of the animals. A day or two later, when Lt. Vladimir Littauer’s squadron found itself suddenly facing rifle fire, one of his troopers pointed towards a farm and shouted, ‘There they are – look!’ They spotted two figures disappearing behind some buildings. Littauer led twenty dismounted men up a convenient ditch, which he later realised marked the Russian frontier with East Prussia. On reaching the farm they found no one. ‘We didn’t know any better than to set it on fire,’ he wrote. ‘This was something our troops were always afterwards doing in similar circumstances.’

The farm they destroyed was on Russian soil, but the young hussar noted ‘something crazy was happening on the German side: houses, haystacks and sheds were ablaze everywhere’ – more wretched consequences of

franc-tireur

fever. Russian units were swept by rumours of a Cossack who asked an East Prussian woman for milk, and was shot dead; of a cavalry division commander who leant from his saddle to ask another woman if she had seen any German troops, only to be greeted by a revolver shot. Civilians on both sides of the border suffered in consequence of such fantasies.

Just eleven German infantry divisions and one of cavalry – 15 per cent of the Kaiser’s host – were deployed for the defence of East Prussia. The inhabitants of this rustic outpost of the Wilhelmine Empire, a flat, melancholy land of cattle, lakes, forests and pasture, had cause for resentment towards their rulers, who had knowingly exposed them to devastation by the rival hosts in order to fulfil their grand strategic vision in France. The role of the relatively small Eighth Army in the east commanded by Gen. Maximilian Prittwitz und Gaffron was not to destroy the Tsar’s forces, an impossible task, but merely to hold a line as best it could; to purchase time until the western legions had crushed the French and could shuttle east for a decisive settling of accounts. Prittwitz’s officers were very conscious of their orphan status. The formations allotted to them represented the left-overs from Germany’s vast deployment in the west. They had a makeshift staff, and their commander was confused by mixed messages from Berlin. Having been instructed before the war that his role was merely to keep the enemy in play, on 14 August Moltke urged him to manoeuvre aggressively in the event that he faced a full-scale thrust: ‘If the Russians come – simply no defence but attack, attack, attack.’ Lt. Col. Max Hoffmann, Prittwitz’s chief of operations, confided to his diary that he found the responsibilities he faced ‘gigantic, and more of a strain on the nerves than I expected’. He observed cynically that if the campaign went well, his general would be hailed as a great captain, while ‘if things do not go well, they will blame us’ – the army staff.

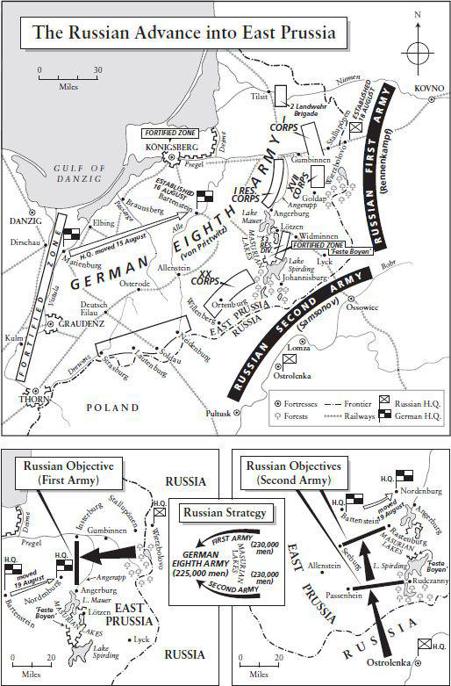

Even as Moltke’s western legions approached Brussels, Prittwitz’s formations met cavalry patrols which were harbingers of two invading armies of almost four times the Germans’ numerical strength. The Russians committed to their northern offensive 480 battalions against the Germans’ 130; 5,800 Russian guns against 774. Sukhomlinov, the war minister, wrote complacently in his diary on 9 August: ‘it seems that the German wolf will quickly be brought to bay: all are against him’. The French, however, were much dismayed by the Russian division of forces. Before the war, the Stavka had professed to accept the importance of ensuring that its forces were concentrated and fully equipped before any advance into German territory began. But in the middle days of August, this prudent resolve crumbled in the face of the overriding imperative swiftly to divert the enemy’s strength and attention from the campaign in the West: the Russians started operations while still lacking 20 per cent of their infantry.

In the midst of East Prussia lay a necklace of large water features surrounded by swamps – the Masurian Lakes. The Russian First Army under Gen. Paul Rennenkampf advanced westwards from a startline north of the lakes, while a few days behind him Aleksandr Samsonov’s Second Army launched itself on a southern axis. The two commanders were thus separated by time, space and some mutual animosity, though the latter has probably been exaggerated. The invaders posted a grandiloquent proclamation: ‘To you Prussians, we the representatives of Russia present ourselves as harbingers of united Slavdom.’ Samsonov conducted himself with reckless braggadocio, dispatching his wireless transmitter back into Poland, then riding forward to reconnoitre without any means of rapid communication. Most telephone lines were cut.

Within hours, almost every Russian horseman screening the left flank of Rennenkampf’s army was riding with a cheese dangling from his saddle, after looting a cheese factory in the town of Mirunsken. ‘A cavalryman is used to many odours,’ wrote one, ‘but never before or after did we smell as we did then.’ For days, they feasted upon a diet of pillaged sausage, ham, pork, geese, chickens, such as few of the Tsar’s soldiers had ever known. If a Russian mount was shot or went lame, the rider exchanged it for a German one: farm horses grazed in the fields, and there were plenty of loose cavalry animals. When the Sumskoi Hussars passed a stud farm, they appropriated all the horses they could catch, muttering teasing words that became commonplace throughout the army, about ‘presents from the grateful local population’. Vladimir Littauer acquired a handsome four-year-old thoroughbred chestnut, but found it vile-tempered.

From the outset, cavalrymen were forced to recognise their vulnerability. Two Hussar squadrons advancing on a village were driven back by rifle fire from a handful of Germans. They retreated, having suffered significant casualties. Littauer struggled to lift a bleeding NCO into a saddle while bullets whipped up dust around them. He suddenly reflected, in a fashion typical of a Russian gentleman among peasants, ‘Why am I helping this man? I hardly know him. Why should I be helping him?’ Then another officer cried out, ‘Watch out for the civilians!’ As if in proof of his words, a shot rang out from a nearby wood, wounding a cornet. As usual, this was attributed to

francs-tireurs

.

The German inhabitants of East Prussia endured Russian looting with grim resignation, but recoiled in fury when they saw local members of the Polish minority joining the pillage of abandoned homes. Schoolteacher Johann Sczuka solemnly noted the names of all whom he recognised – especially his own pupils – with a view to future retribution. He rebuked a woman he met near his village, laden with booty, but she brushed him off and marched defiantly onwards, clutching her spoils. Some Russian officers showed themselves surprisingly humane and sensitive. Martos, one of Samsonov’s corps commanders, expressed embarrassment about being billeted in a house still adorned with the possessions and photographs of its German owners, now fugitives. One day when he encountered some children roaming unattended on the battlefield, he removed them to the rear in his own car.

The long columns plodding forward into German territory filled observers with wonder at their exotic character and mingling of modern and primitive equipment. Many of the infantry lacked high boots. Supply

arrangements were chaotic and inadequate, hampered by poor roads and few railways in their rear. The Russian army rejected howitzers as a ‘cowards’ weapon’, because they could be fired by men beyond sight of their enemies; for artillery support, they relied exclusively upon field guns. Communications were hampered by a shortage of radios, and commanders were obliged to signal in plain language, because each corps used a different cipher. The invaders owned a total of just twenty-five telephones and eighty miles of wire. The cavalry were trained to act chiefly as mounted infantry, filling gaps between corps, and made little attempt to fulfil the vital reconnaissance role. Most of Russia’s few available aircraft had been sent to Galicia, and those in East Prussia were temporarily grounded for lack of fuel.

In 1910 German writer Heino von Basedow described his impressions of the Tsar’s army in terms which reflected widespread foreign opinion: ‘The Russian soldier is impulsive as a child. He is easily excited by rabble-rousers (towards revolt) but equally readily restored to submission.’ Basedow was amazed by the careless culture of the Tsar’s soldiers, symbolised by the rakish angle at which each man wore his cap. An NCO calling ‘

ras-dwa

’ at the front of a marching column in hopes of maintaining its step and precision could not prevent a man in the rear rank from casually munching an apple. Soldiers supposedly marching at attention would nonetheless raise an unfailing hand to cross themselves when they passed a church or roadside icon. Meanwhile a grenadier might seat himself on a roadside marker and hawk his platoon’s bread to all comers. Such a way of soldiering did not inspire German respect. Alfred Knox noted the same casualness on the battlefield, where he was astonished to see Russian artillerymen sleeping huddled against their gunshields, minutes before they were due to open fire.

Rennenkampf and Samsonov groped forward, sharing with the Germans uncertainty about each other’s whereabouts. The Russians occupied the town of Lyck, only to be almost immediately obliged to evacuate it. This news failed to reach a Tsarist officer who drove smartly up to the Königlicher Hof hotel and stepped out of his automobile to find himself a prisoner of war; it profited him nothing that his compatriots recaptured Lyck a few hours later. There were daily clashes between patrols of the rival armies, riding hither and thither between towns and villages, sometimes firing on their own side in the general confusion.

Many German and Russian soldiers were exhausted by epic marches before they even began to fight. Some of Samsonov’s men trudged 204

miles from Białystok in fifteen days. One of Prittwitz’s corps spent twelve days footslogging from Darkehmen – 186 miles – and then immediately engaged the enemy on the morning of 20 August. Its commander, Gen. August von Mackensen, ordered an assault on Rennenkampf’s army near the village and rail junction of Gumbinnen, some twenty miles inside East Prussia. The Germans drove in the Russian flanks with impressive ease. In the centre, however, they suffered a bloody repulse which made their other gains worthless. Advancing across open ground in extended lines –

Schützenlinien

– they met the fire of two entrenched divisions. Mackensen’s men had been marching twenty hours without sleep; their waterbottles were empty. Their tactics were no more subtle than those of the French army in Alsace-Lorraine, and were similarly rewarded.

One Russian regiment’s 3,000 rifles and eight machine-guns fired 800,000 rounds that day. Its supporting artillery did formidable execution: Russian gunnery showed an excellence it would reprise on future battlefields. Thousands of Germans were mown down – one man in four – while many of the survivors fled in panic, and kept running for hours. A Grenadier lieutenant sought to encourage his men by shouting defiantly that the Russians were hopeless marksmen, until he fell dead with a bullet in his breast. Thousands of wounded lay untended. Mackensen’s cavalry became separated from the infantry, and rejoined only days later, worn out. At nightfall, the Gumbinnen battlefield was strewn with the casualties of both sides. When at last some of these were brought into field hospitals, a Russian officer noticed a German private soldier, prostrate on a stretcher, smoking a cigar. Though this stogie was no costly product of Cuba, the Hussar nonetheless marvelled at the wealth of an enemy society which permitted a humble rifleman access to such a luxury as no Russian ranker could dream of.