Catastrophe 1914: Europe Goes to War (49 page)

Read Catastrophe 1914: Europe Goes to War Online

Authors: Max Hastings

Tags: #Ebook Club, #Chart, #Special

Tannenberg: ‘Alas, How Many Thousands Lie There Bleeding!’

The peoples of Europe were awed by the scale of the forces unleashed across the continent. ‘Russian society had not experienced such emotions since the 1812 war,’ wrote Sergei Kondurashkin. ‘A great battle was to be fought on the threshold of one’s own home. Men who had been reservists for as long as seventeen years were called up – six million men … A sea of people against another sea of people … One’s imagination was unable to grasp the scale of the coming events.’ But once even the Russian hosts were dispersed across fronts of many hundreds of miles – three times the length of those contested in the west – suddenly they became much less impressive than when passing in review across parade grounds. A dominant theme of the campaigns of 1914 was the mismatch between the towering ambitions of Europe’s warlords, and the inadequate means with which they set about fulfilling them.

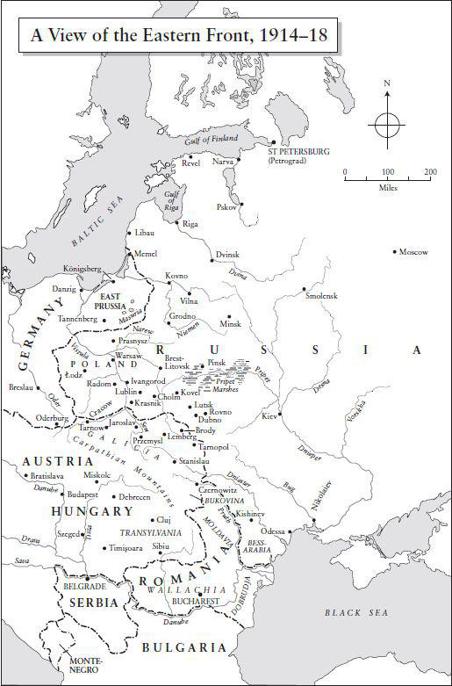

On the Eastern Front, reason should have told the Stavka – the Tsar’s high command – that Germany was the critical enemy: if Russia could achieve quick victories against the Kaiser’s relatively small army in East Prussia, the impact on the whole war would be dramatic, conceivably decisive. That is what the French government wanted, and implored the Russians to attempt. Contradictorily, however, Gen. Alexei Speyer, most respected of Russia’s strategic planners, urged smashing the Austrians before making any attempt to take on the Germans. The Stavka, which established itself in a pine forest beside a railway junction at Baranovichi in Belorussia, deliberated, wavered, then committed the mirror error of Conrad Hötzendorf’s. The Russians divided their armies, and attempted to attack both foes simultaneously. Two-thirds of their immediately available forces – 1.2 million men – were sent to fight the Austro-Hungarians in southern Poland, while half that number attacked the Germans in East Prussia.

Moltke had taken a large risk by deploying only a blocking force to hold the Russians in play, and now his gamble was to be put to the test. The

Kaiser’s eastern subjects were acutely conscious of the proximity of a hated and feared enemy to their homes. Berlin’s

Neue Preußische Zeitung

was known as ‘the Cross newspaper’ –

Kreuzzeitung

– because its masthead bore an iron cross. On 6 August 1914 it spoke of the ‘cross of Prussia’s Teutonic Knights’ rising again to fight the barbarians from the east. During the first weeks of war, memories of the knights were often invoked. Fears ran deep that ‘Russian hordes’ might sweep forth towards Berlin, wrecking and pillaging.

In the late summer of 1914, from every corner of Nicholas II’s empire the armed might of Mother Russia converged upon its Polish colony, focus of operations against both Germany and Austria. The Tsar wanted to take personal command of his armies in the field, but was persuaded instead to appoint a figurehead commander-in-chief, his uncle Grand Duke Nicholas – often known as ‘Nicholas the tall’ to distinguish him from the Emperor, ‘Nicholas the short’. The Grand Duke’s personal train crawled slowly along the Vitebsk line towards the theatre of war. Three-course lunches and dinners were served, with plenty of claret and Madeira. The French military attaché, Gen. Marquis de Laguiche, expostulated in frustration, ‘Think of me – with thirty-eight years’ service, having dreamt so much of this moment, and now stuck here when the hour has come.’

Amid desultory time-passing conversation, the Grand Duke told British military attaché Maj. Gen. Alfred Knox of his impatience to get to England for some shooting once the war was disposed of – he was a passionate hunter. He spoke of his distaste for the Germans, and said that once they had been beaten the

Kaiserreich

must be broken up. As royal soldiers go, Nicholas commanded some respect, but he had always been a trainer of troops rather than a field commander. He lacked both the delegated authority and the force of personality effectively to coordinate the operations of Russia’s generals in Poland. When at last they reached Baranovichi on the morning of Sunday the 16th, flippancy was still to the fore. A Foreign Ministry official said to Knox, ‘you soldiers ought to be very pleased that we have arranged such a nice war for you’. He received a cautious response: ‘We must wait and see whether it will be such a nice war after all.’

Train after train bore to Warsaw and beyond horse, foot and guns of one of the most exotic military hosts the world has ever seen. Many infantry officers were of peasant stock, while most generals and cavalry leaders were aristocrats. Not all Russian commanders were incompetents, although in

the early months of the war they displayed no more military genius than most of their French and Austrian counterparts. Especially in the early months, cavalry played a much larger role on the Eastern Front than in the west. Foreign observers never failed to be impressed by the exotic regiments of the Tsar – Don, Turkistan and Ural Cossacks, the latter ‘big, red-bearded, wild-looking men’. Officers carried their maps in their high hats; many enemies were killed with the lance. And there were astounding numbers of Russian horse: to conduct one raid, Gen. Novikov’s corps deployed 140 squadrons. As for the men, correspondent Alexei Ksyunin wrote: ‘The yellow and purple robes of the Turkmens appeared blindingly brilliant against the background of village houses. They wore enormous sheepskin hats, above dark features and wild hair which made them seem picturesque and majestic. Galloping on their horses they caused no less panic than armoured vehicles. I offered cigarettes and tried to talk to them. It was useless, for they didn’t speak any Russian. They could say only “Thank you, sir,” and nothing more.’

An American correspondent described a squadron of Kubanski Cossacks: ‘a hundred half-savage giants, dressed in the ancient panoply of that curious Slavic people whose main business is war, and who serve the Tsar in battle from their fifteenth to their sixtieth years; high fur hats, long caftans laced in at the waist and coloured dull pink or blue or green with slanting cartridge pockets on each breast, curved yataghans inlaid with gold and silver, daggers hilted with uncut gems, and boots with sharp toes turned up … They were like overgrown children.’ First Army’s cavalry were commanded by the old Khan of Nakhichevan, who was found weeping in his tent one morning because he was too crippled by haemorrhoids to mount his horse.

Some of the Tsar’s officers were conscientious professionals, but others behaved towards their men like country landlords among serfs. Foreigners were shocked by commanders who, when their regiments halted for the night, set off in search of women, leaving horses and men to shift for themselves. Cossacks were sometimes seen thrashing their whips to halt fleeing infantry. Provisioning arrangements were casual: the army was expected to subsist chiefly off the land, though every column carried supplies of

sukhari

, a dried black bread which substituted for biscuit, packed loose in sacks.

Poland was the Russian Empire’s critical salient: there the Tsar’s armies could grapple their foes, but were also threatened by counter-strokes. Russian soldiers newly arrived in the region were impressed by the living conditions of rural Poles, whose houses were adorned with such unfamiliar refinements as soft furniture and lace curtains. German settlers lived among the peasants, and in that polyglot region it was hard to guess what language might prove comprehensible to local people. When a Russian officer demanded first in Polish, then in Russian, whether a farming family had any produce to sell, he was met by blank stares. He fared better in German, but the old farmer, already embittered by experience, responded, ‘What produce?’ He shifted in his chair, looking scared. The officer said, ‘How come you didn’t store anything in the summer?’ ‘We sold everything.’

The Eastern theatre of war must be understood as a colonial region, in which Russians, Austrians and Germans alike ruled minorities – Poles, Bosnians, Czechs, Serbs, Jews – whose loyalty to their respective empires was anything but assured. This reinforced paranoia about spies and saboteurs, even stronger here than on the Western Front, as the armies of three empires began to skirmish across their respective frontiers. Jews were considered the natural prey of any passing Russian patriot. The Belobeevsky infantry regiment’s train halted for two hours at the Polish station of Tłusz. Many men slipped away into the town, seizing goods for which they declined to pay Jewish shopkeepers. In response the traders put up their shutters, prompting the soldiers to break down doors and commence uninhibited looting, while their officers stood by and watched. The episode would have gone unremarked had not a passing general expressed outrage. The next day in Lublin, twenty Jewish stores were systematically pillaged by troops. Josh Samborn has written: ‘soldiers knew that their word would be honoured over that of a Jew, and even the murder of robbed Jews went largely unpunished’.

A Russian gendarme telegraphed to his superior, reporting that in Vyshov ‘in the guise of buying horses, two Germans arrived who stayed the night in the barn of the Jew Gurman and then went to Ostrolenka’. On 18 August in Tarchin, an outbreak of fires as Russian troops marched through the town was immediately blamed upon Jews ‘with the goal of letting the enemy know where our troops were moving’. Fourteen such hapless men were arrested. Unusually, they were later freed when the local police chief concluded that the fires had started accidentally, but their pillaged goods were not returned or compensated. Through the months that followed, a series of pogroms against Jewish communities was conducted chiefly, though not exclusively, by Cossacks. A considerable number of Jews took flight to Warsaw, from whence they were forcibly deported eastwards.

Lt. Andrei Lobanov-Rostovsky was a twenty-two-year-old sapper, bookish, widely travelled, the son of an aristocratic diplomat. He described how in a small Polish town his unit of newly mobilised soldiers murdered

eight Jews following an outbreak of spy fever. That afternoon, as the men prepared for mass they saw a partial eclipse of the sun; this caused the superstitious soldiers to become troubled about their deeds of the morning. But their consciences were quieted soon enough: Russian troops in Poland seized anything they could snatch on their line of march, heedless of the fact that the victims were supposedly their own compatriots. For the overwhelming majority of the Tsar’s subjects, foreigners began in the next village to their own. Though Gen. Paul Rennenkampf issued stern edicts against looting on Russian territory, and on 10 August announced that four men had been shot for robbing civilians, his subordinates made little or no attempt to enforce his orders. Pillage had a severe impact on local trade, harming both civilians and soldiers. Commissary officers, struggling to feed their men, found it hard to secure local produce, even where the army was willing to pay.

On the other side, in the first days of the war the Germans acted as savagely as in Belgium, destroying the Polish border towns of Kalitz and Częstochowa, taking hostages and murdering civilians. After occupying Kalitz on 2 August, the invaders became obsessed by reports of civilian snipers, and began firing at will on the inhabitants. Suspected ‘ringleaders of

francs-tireurs

’ were taken hostage along with civil and religious dignitaries: 750 people were soon in custody. There was widespread rape, pillage and arson. The Germans admitted to executing eleven civilians, but locals said the real total was much higher. When the invaders withdrew, from mere spite they unleashed an artillery bombardment on the town, obliging tens of thousands of Poles to flee.

The Russian Sumskoi Hussars, who detrained at Suvalki on 3 August, rode towards the East Prussian border through a contraflow of dusty, desperate refugees, trekking away from the front on foot, or driving carts laden with their scanty possessions. Mutual fears provoked civilian migrations alike in Poland, East Prussia and Galicia. A woman refugee at a Red Cross depot in Schneidemühl kept crying out, ‘Where can we go? Where can we go?’ She looked down at twelve-year-old Elfriede Kuhr and said, ‘A girl like you can have no idea what it’s like, can you?’ Elfriede wrote: ‘Tears ran down her chubby red cheeks.’ A few days later the child wrote with pathetic naïveté: ‘Gretel and I now play a game in the yard in which her old doll is a refugee child that has no more nappies. She has painted its behind red, to show that it is sore.’

In 1914, East Prussia had not experienced war for a century – a long respite, in the turbulent history of the region. Across its vast, open,

underpopulated flatlands, at first each side’s lancers roamed at will, like naval privateers of bygone ages, engaging like-minded foes or attacking villages according to the whim of their commanders. Often the only means by which a patrol could discern the whereabouts of the enemy was by scanning the horizon for pillars of smoke, beacons of domestic tragedy. Cavalry officer Nikolai Gumilev grew accustomed to coming upon houses whose owners had just fled, sometimes leaving behind coffee on the stove, knitting on the table, open books. As he availed himself of such creature comforts, ‘I remembered the children’s story about the little girl who entered the house of the bear family, and I was constantly expecting to hear the angry demand: “Who ate my porridge? Who slept in my bed?”’