Charles Dickens: A Life (57 page)

Read Charles Dickens: A Life Online

Authors: Claire Tomalin

Tags: #Biographies & Memoirs, #Arts & Literature, #Authors

Walter had got into debt and Dickens was angry with him and had not been in contact for many months. There had been a note from Walter to Mamie in the autumn to say he was ill, and another at Christmas telling her he was now so ill that he was about to be sent home on sick leave; but before he could be embarked he died, of an aneurism, on the last day of 1863. Miss Coutts took the opportunity of Walter’s death to write to Dickens, again urging a reconciliation with Catherine. His reply said that ‘a page in my life which once had writing on it, has become absolutely blank, and that it is not in my power to pretend that it has a solitary word upon it.’

31

He neither spoke nor wrote to Catherine about the death of their child, but paid off Walter’s debts and hardened his heart.

32

Francis and Alfred, in their late teens, both disappointed him. In October, Francis failed to get into the Foreign Office after coming second in a competitive examination, despite having been nominated by Lord John Russell and coached by a senior civil servant. His stammer may have stood in his way, but Dickens found his failure ‘unaccountable’ and applied to Lord Brougham to get him a place in the Registrar’s Office in London. When this too proved impossible, Francis agreed to go to India to join the Bengal Mounted Police and left for India in December 1863, expecting to see his brother Walter. At the same time Alfred’s preparations to take the Army examinations for Woolwich were thought by his teachers so unlikely to succeed that Dickens decided to put him into a firm in the City, and when he failed to do well there he was persuaded to go to Australia. In May 1865, as Dickens left for France, Alfred sailed for Australia to become manager of a sheep station in New South Wales. He saw neither of his parents again.

Professionally things were better, as we have seen. After two years with no novel planned, at the end of August 1863, returning from France, Dickens told Forster he had an idea for a new story that would make a twenty-number novel, and by October he declared himself fairly confident of it, and it became

Our Mutual Friend

.

33

He also did good among his own friends that autumn, reconciling Forster and Macready after a long estrangement brought about by Forster’s disapproval of Macready’s remarriage. In February 1864 he complained of some of his private correspondence being published, destroyed a further batch of letters received, declared he would write ‘as short letters as I possibly can’ in future and visibly carried out his intention.

34

There were no readings in 1864. He took a house at Gloucester Place, Hyde Park Gardens, until June, and refurbished his rooms at Wellington Street, choosing handsome new carpets for them. In March, after his visit to France, he wrote to Forster praising his new biography of the seventeenth-century statesman Sir John Eliot, and arranged for it to be prominently reviewed in

All the Year Round.

He told Forster he was working very slowly on his novel and wanted to have five instalments ready before the first number appeared on 30 April. On 23 April he celebrated Shakespeare’s birthday ‘in peace and quiet’, going to Stratford for the day with Forster, Robert Browning and Wilkie Collins.

35

In the autumn another dear friend, the artist John Leech, not yet fifty, died, and Dickens went grimly to the funeral at Kensal Green, remembering their cheerful family holidays together, their walking club, their theatricals and Leech’s much admired illustrations for the Christmas books. Then came the death of Joseph Paxton in June 1865, with whom he had set up the

Daily News.

A new friend appeared to fill some of these losses: Charles Fechter, who in January 1863 became manager of the Lyceum Theatre, just opposite the Wellington Street office. Fechter was partly English, partly German, his education had been largely in France, French was his first language, and he had started his career in the theatre in Paris in the 1840s, becoming a star, but a quarrelsome one. Dickens had admired his acting in Paris, and when he moved to London in 1860 he made a point of seeing him again. He gave a thrilling and much praised Hamlet, his naturalism breaking with all the traditions, and a great Iago. His English was accented but good; his nerves made him vomit before each performance. He was famous for his bad temper, he borrowed money and was generally unreliable, yet Dickens took to him strongly, praising him for being ‘a capital fellow and an Anti-Humbug’.

36

During the summer of 1864 he said Fechter usually came to Gad’s on Sundays when he was there, and by 1865 he described him as ‘a very intimate friend’ and proposed him for membership of the Athenaeum.

37

Not surprisingly, the Athenaeum turned him down, but the Garrick Club welcomed him. English gentlemen’s clubs were centres of intrigue, gossip and quarrels, and when Wills was blackballed by the Garrick and Dickens resigned – it was his fourth resignation – Fechter loyally followed suit.

Fechter never fitted into English society, entertaining in his dressing gown and sending guests to fetch their food from the kitchen. He was married to a French actress, became the lover of another, Carlotta Leclerq, whom he abandoned later for a third, and this Gallic

sans-gêne

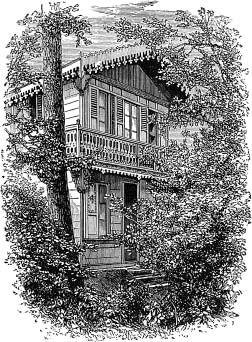

had its appeal for Dickens, as D’Orsay’s flouting of respectability had done, perhaps because it allowed him to become someone different himself when he was with them. Fechter made his own mark upon Gad’s Hill when, in January 1865, he was inspired to give Dickens a perfect present: a great box full of all the parts needed to build a two-storey wooden Swiss chalet. Dickens had it put up at once. Set well away from the house, in the wilderness reached only through a tunnel he had built under the road, it gave him an airy upstairs writing room – ‘a most delightful summer atelier’ – hung with mirrors and full of light and birdsong.

38

Here he could escape from people, letters, anxieties, troubles, and work uninterrupted.

The chalet given to Dickens by Fechter in 1865 – a perfect present.

Wise Daughters

From the autumn of 1863 until the autumn of 1865, Dickens was writing

Our Mutual Friend.

It was to be his last completed novel. He did no readings during the two years it took, and although they were years of stress the book he made was an ambitious and powerful piece of work, full of sardonic humour and offering his final judgement on the society in which he lived. He had been hailed as a young writer for his echoing of Hogarth, and in this late work there is still a Hogarthian vigour and precision in his drawing of scenes and characters, no smoothing over of rough places, physical or moral deformities but rather a relish for them. He chose not to run it in

All the Year Round

but serialized it in twenty monthly numbers in green-paper wrappers in the old way. He also signed a contract with Chapman & Hall that raised for the first time the possibility that he might not live to finish a work, in which case Forster would negotiate compensation to the publishers. All being well, Dickens would be paid in three instalments: £2,500 on publication of the first number, and again at the sixth, then £1,000 at the end, a grand total of £6,000.

1

Knowing himself to be less energetic than he had been, he decided to have five instalments written before the first number appeared in April 1864. There were times when he became anxious about keeping up the pace, and in July, telling Forster he had been unwell and was still out of sorts, he complained that he had ‘a very mountain to climb before I shall see the open country of my work’.

2

It did not help to find that sales were lower than those for any of his recent books. The starting monthly print order of 40,000 fell until, for the final number, only 19,000 copies needed to be stitched into paper covers;

3

but it attracted more advertising than any serial yet, making £2,750 to be shared equally between publishers and author. And the book has endured.

Our Mutual Friend

offers us his last look at London, the London of the 1860s, ‘a black shrill city, combining the qualities of a smoky house and a scolding wife; such a gritty city; such a hopeless city, with no rent in the leaden canopy of its sky’.

4

A city too in which people starve to death in the streets every week; and in which the middle classes are shown as corrupt, complacent, lazy, greedy and dishonest, more interested in the pursuit of shares than the pursuit of love. Among the rich and would-be rich he mocks are the Lammles, a confidence man and woman who marry, each under the delusion that the other has money; Veneering, a corrupt businessman going into parliament; and Podsnap, an insurance broker convinced of the superiority of the British over all other nations and set on ignoring any aspect of life that might trouble his complacency. Their good friend Lady Tippins, widow of ‘a man knighted by George III in mistake for somebody else’ and invited to raise the tone at the Lammles’ wedding, makes private observations to herself in the church: ‘Bride; five and forty if a day, thirty shillings a yard, veil fifteen pounds, pocket-handkerchief a present. Bridesmaids; kept down for fear of outshining bride, consequently not girls … Mrs Veneering; never saw such velvet, say two thousand pounds as she stands, absolute jeweller’s window, father must have been a pawnbroker, or how could these people do it?’

5

We are into the comic world of Oscar Wilde or Noel Coward with this nasty, witty old woman’s inner monologue.

Other characters inhabit the new London that is spreading haphazardly around the old: ‘that district of the flat country tending to the Thames, where Kent and Surrey meet, and where the railways still bestride the market-gardens that will soon die under them … a toy neighbourhood taken in blocks out of a box by a child of particularly incoherent mind … here, another unfinished street already in ruins; there, a church; here, an immense new warehouse; there, a dilapidated old country villa; then, a medley of black ditch, sparkling cucumber-frame, rank field, richly cultivated kitchen-garden, brick viaduct, arch-spanned canal … As if the child had given the table a kick and gone to sleep.’

6

There is always a lot of mess and dirt in Dickens’s London. Waste paper blows through the streets, and much of the plot relates to the great dust heaps piled up in Camden Town, rubbish that is worth a fortune once it has been sorted, making its owner into a ‘Golden Dustman’. Dickens had published a description of the real dust heaps in

Household Words

in 1850,

7

and some critics have seized on them as symbols in the book; although, as John Carey points out, if they are meant to suggest that money is dirt, and that the accumulation of money is bad, this hardly fits with Dickens’s view of money, which he valued and worked hard to earn.

8

The thing itself always fascinated Dickens more than whatever it might symbolize or represent.

Something that had not changed much since the 1830s when he first wrote about it was the condition of City clerks, travelling to work from northern suburbs through a ‘suburban Sahara’ of dust heaps, dog fights, rubbish heaps, bones, tiles and burning bricks.

9

They came further now, but were still likely to live in small and inconvenient houses and to have to share them with lodgers in order to keep up with the rent: in Holloway, Reginald Wilfer’s family lets out the best rooms in the house to a lodger. The Wilfers are usually short of candles and low on food, often with nothing more than an old piece of Dutch cheese for supper, and when they have something better they fry it up over an open fire. The grown-up daughters share a room furnished with an upturned box and a small piece of glass for a dressing table, and they do not stand on ceremony, Bella coming downstairs in bare feet, with her hairbrush in her hand, to talk to her father. Dickens knows exactly how they live, perhaps with an echo of the Ternan household as he had seen it at Park Cottage.

His characters, like Dickens himself, leave town in order to feel better. They go to Blackheath or Greenwich, or along the Thames towards Hampton and further west – Staines, Chertsey, Walton, Kingston, where there are trees and green fields – as far as Oxfordshire: we remember Dickens’s solitary boat trip when he rowed himself from Oxford to Reading in June 1855. Yet even out there the Thames has its sinister side, since people can drown or be drowned as easily as in town; and there are many drownings and near-drownings in

Our Mutual Friend.

Violence and danger threaten many of the characters, and Lizzie Hexam, who is attached to the Thames from having grown up alongside it at Limehouse, also sees it as ‘the great black river with its dreary shores … stretching away to the great ocean, Death’.

10