Chasing Gold: The Incredible Story of How the Nazis Stole Europe's Bullion (54 page)

Read Chasing Gold: The Incredible Story of How the Nazis Stole Europe's Bullion Online

Authors: George M. Taber

BOOK: Chasing Gold: The Incredible Story of How the Nazis Stole Europe's Bullion

3.35Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

Puhl later met with

SS

Brigade-Führer Karl Hermann Frank and Obergruppenführer Karl Wolff, both high ranking

SS

officers, to work out the details of the shipments, and all agreed to handle everything verbally and to put nothing in writing. Puhl informed Bank Director Frommknecht, the member of the board in charge of the vault, who called in Albert Thoms, the manager of the Precious Metals Department and the person who would be running the day-to-day operations. Frommknecht explained that the

SS

would soon be bringing him deliveries, again emphasizing that they came from the “eastern occupied territories.”

SS

Brigade-Führer Karl Hermann Frank and Obergruppenführer Karl Wolff, both high ranking

SS

officers, to work out the details of the shipments, and all agreed to handle everything verbally and to put nothing in writing. Puhl informed Bank Director Frommknecht, the member of the board in charge of the vault, who called in Albert Thoms, the manager of the Precious Metals Department and the person who would be running the day-to-day operations. Frommknecht explained that the

SS

would soon be bringing him deliveries, again emphasizing that they came from the “eastern occupied territories.”

The two men then went to see Puhl, who said that the matter was to be kept “absolutely secret” and that the delivery would include several different types of valuables including jewelry. Puhl warned Thoms that if anyone ever asked him about it, he should not discuss the subject. Thoms was given the names of two

SS

officers whom he should contact if he had any questions about the upcoming deliveries.

SS

officers whom he should contact if he had any questions about the upcoming deliveries.

Thoms protested that he would need to use outside experts to evaluate the material they were talking about, but Puhl said that should be handled some other way. The deputy suggested that the jewelry be dealt with exactly as the bank had treated earlier confiscated Jewish property in the aftermath of

Kristallnacht

in 1938 by sending it to the Municipal Pawn Shop in Berlin, which would then later forward a payment to the bank. Puhl accepted the proposal.

3

Kristallnacht

in 1938 by sending it to the Municipal Pawn Shop in Berlin, which would then later forward a payment to the bank. Puhl accepted the proposal.

3

After going back to his office, Thoms called one of the names he had been given and learned that in two weeks

SS

Hauptsstrumführer Bruno Melmer would deliver the first shipment. The

SS

had already decided that it would be better if he arrived in civilian clothes, although other soldiers in uniform would accompany him to help move the valuables expeditiously. Bank officials gave the name Melmer to all the deliveries, and a tag with that word was put on each container the

SS

delivered. Thoms and his staff followed orders and did not put the letters “

SS”

anywhere in the bank’s books.

SS

Hauptsstrumführer Bruno Melmer would deliver the first shipment. The

SS

had already decided that it would be better if he arrived in civilian clothes, although other soldiers in uniform would accompany him to help move the valuables expeditiously. Bank officials gave the name Melmer to all the deliveries, and a tag with that word was put on each container the

SS

delivered. Thoms and his staff followed orders and did not put the letters “

SS”

anywhere in the bank’s books.

The first shipment arrived on August 26, and the contents were immediately distributed to various bank departments. The currency and stock certificates went to the currency group, while the jewelry and gold coins stayed in the Precious Metals Department. The items generally arrived in battered suitcases, although some were also in canvas bags. Melmer provided his own list of the contents at each delivery, and received a receipt for the goods when he left. Unloading the first shipment took four days, but the second one only two.

It had been agreed between the bank and the

SS

that the proceeds of shipments would be deposited in a new

SS

account at the German Finance Ministry. The code name for the account was Max Heiliger. There was no such person, and it is an example of

SS

humor since in German the surname means “Holy One.” Max is a common German first name.

SS

that the proceeds of shipments would be deposited in a new

SS

account at the German Finance Ministry. The code name for the account was Max Heiliger. There was no such person, and it is an example of

SS

humor since in German the surname means “Holy One.” Max is a common German first name.

The deliveries were erratic. There was one in August 1942, then three in September and back to one in November. In March 1944, there were four shipments.

4

The concentration camp suitcases contained a wide variety of items. One listed simply as Case 71, for example, held 1,536 bracelets made out of gold, silver, and lacquer. In another there were 2,656 gold watchcases. In a third was Polish currency totaling 850,300 zloty. Some contained hundreds of pieces of silverware. Teeth fillings were separated into gold and silver containers, and in one of the early suitcases there was twenty-two pounds of dental silver. The first gold teeth appeared in the November 1942 delivery. Eighteen bags contained bars of silver and gold. There were also gold cufflinks, tiaras, silk stockings, and Passover cups, as well as pearl necklaces. In short, the cases contained anything people who had been told they were being relocated to a new place would have wanted to take with them.

4

The concentration camp suitcases contained a wide variety of items. One listed simply as Case 71, for example, held 1,536 bracelets made out of gold, silver, and lacquer. In another there were 2,656 gold watchcases. In a third was Polish currency totaling 850,300 zloty. Some contained hundreds of pieces of silverware. Teeth fillings were separated into gold and silver containers, and in one of the early suitcases there was twenty-two pounds of dental silver. The first gold teeth appeared in the November 1942 delivery. Eighteen bags contained bars of silver and gold. There were also gold cufflinks, tiaras, silk stockings, and Passover cups, as well as pearl necklaces. In short, the cases contained anything people who had been told they were being relocated to a new place would have wanted to take with them.

Thoms passed along as much of the Melmer deliveries as he could to other organizations, without telling them the origin of the goods. Jewelry went to the Municipal Pawn Shop in Berlin, as he had suggested. Items in good condition, such as gold bars, were sent directly to the Prussian Mint, where they were melted and given predated identification numbers to hide their original identity. Boxes of gold wedding rings also went to the Prussian Mint. Lower quality gold from other jewelry went to Degussa, a German precious metal company, which smelted it into higher-quality bars. Several Reichsbank officials were charged with handling other specific goods.

5

5

After the first shipment arrived at the Reichsbank, Oswald Pohl of the

SS

called Emil Puhl and asked him if he knew about the deliveries. The banker said yes, but then added that he did not want to talk with him about it on the phone. He asked the

SS

officer to come to his office so they could discuss the matter in person. Pohl arrived with an assistant and said that he already had a large quantity of jewelry in Berlin and wondered if he could bring it to the bank. Puhl replied that he would try to arrange it. After the war, the bank managing vice president told interrogators that he informed the board of directors about the first shipment at its next meeting. No one raised any objections to this new work with the

SS

.

6

Bruno Melmer personally delivered all of them until late in the war, when Sturmführer Furch took over the job.

SS

called Emil Puhl and asked him if he knew about the deliveries. The banker said yes, but then added that he did not want to talk with him about it on the phone. He asked the

SS

officer to come to his office so they could discuss the matter in person. Pohl arrived with an assistant and said that he already had a large quantity of jewelry in Berlin and wondered if he could bring it to the bank. Puhl replied that he would try to arrange it. After the war, the bank managing vice president told interrogators that he informed the board of directors about the first shipment at its next meeting. No one raised any objections to this new work with the

SS

.

6

Bruno Melmer personally delivered all of them until late in the war, when Sturmführer Furch took over the job.

In early 1943, some of the packages began carrying stamps identifying them as Lublin or Auschwitz. The Reichsbank staff knew that those were the names of death camps. Puhl rarely visited Thoms and his operation, but on one occasion Funk had a dinner for Oswald Pohl, the Himmler aide. Before they ate, Emil Puhl took the concentration camp inspector down to the cellar vaults so that he could see the suitcases of looted valuables that his men were bringing to the bank.

7

After a few months of deliveries, Puhl telephoned Thoms and asked him how the operation was going. The vice president said that he thought they would soon be over. Thoms replied that it looked to him like they were increasing.

7

After a few months of deliveries, Puhl telephoned Thoms and asked him how the operation was going. The vice president said that he thought they would soon be over. Thoms replied that it looked to him like they were increasing.

When the Allied bombing of Berlin became devastating and targeted, it was more and more difficult to handle the shipments of prison camp gold and other valuables. Piles of unopened suitcases began to stack up in the Reichsbank basement. Degussa’s main facilities were destroyed by Allied attacks in late 1944, and it could no longer smelt gold.

Thoms told American interrogators that the total value of all of the deliveries was about ten million marks, but he was likely underestimating it. At the official 1940 dollar-mark exchange rate of 2.5, that would have been the equivalent of $4 million. Bernstein calculated the Melmer proceeds from the deliveries at $10 million. While most of the bullion was in small amounts, 125 pounds came in the form of bars. Later post-war estimates ranged between $2.5 million and $5.0 million, but no one knows for certain. In addition, there were 6,427 gold coins. Those two categories alone amount to nearly eleven tons. The theft of valuables from people on their way to death camps ranks among the most despicable of the many Nazi atrocities. The seventy-sixth and last Melmer delivery arrived at the Reichsbank on January 27, 1945.

8

8

Eisenhower was not comfortable with money and gold issues, but he had someone to handle them for him. In the summer of 1942, General Eisenhower sent Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson a message saying that he would need an expert to handle financial and monetary issues when American armies began invading Nazi-held parts of North Africa and Europe. Stimson picked up the phone and asked Morgenthau if he had someone for Eisenhower. The Secretary of the Treasury replied that Bernie Bernstein, his assistant general counsel, was just the man. Morgenthau thought he had both the youth and the experience needed for the obviously demanding job. Bernstein immediately received the rank of Lt. Colonel and was soon working for Eisenhower in London. When allied forces soon invaded North Africa and Italy, Bernstein handled delicate occupation issues such as local currency values and military script.

In a May 8, 1945 report entitled “

SS

Loot and the Reichsbank,” Bernstein estimated the value of the Melmer deposits to be $14.5 million.

9

In his conclusion he wrote: “The sums estimated by Thoms appear to be an understatement for the loot handled by the Reichsbank since 1942. Certainly they cannot begin to represent the total extent of the operations of the

SS

economic department, which for 12 years has disposed of the personal and household valuables of millions of racial and political victims of the calculated Nazi policy of extermination.”

10

SS

Loot and the Reichsbank,” Bernstein estimated the value of the Melmer deposits to be $14.5 million.

9

In his conclusion he wrote: “The sums estimated by Thoms appear to be an understatement for the loot handled by the Reichsbank since 1942. Certainly they cannot begin to represent the total extent of the operations of the

SS

economic department, which for 12 years has disposed of the personal and household valuables of millions of racial and political victims of the calculated Nazi policy of extermination.”

10

In Bernstein’s May 1945 monthly report to General Clay, he updated his estimate on the amount of Melmer gold deposited at the Reichsbank. This was based on further interrogations of Albert Thoms and other bank officials. A 1998 study by William Z. Slany, a U.S. State Department historian who did extensive work on the topic for the 1997 London Gold Conference, estimated the amount of looted

SS

bullion at $4.6 million.

11

SS

bullion at $4.6 million.

11

There is no doubt that some gold taken from concentration-camp victims has found its way into bars and today sits in the world’s central banks vaults, probably including those of the New York Federal Reserve. Several ingots of Melmer gold were sold to Switzerland and then moved into the traffic of central bank bullion.

12

It is impossible, though, to determine how much. When gold is melted down and resmelted, it loses all identification. It would be like trying to identify a grain of wheat in a loaf of bread.

12

It is impossible, though, to determine how much. When gold is melted down and resmelted, it loses all identification. It would be like trying to identify a grain of wheat in a loaf of bread.

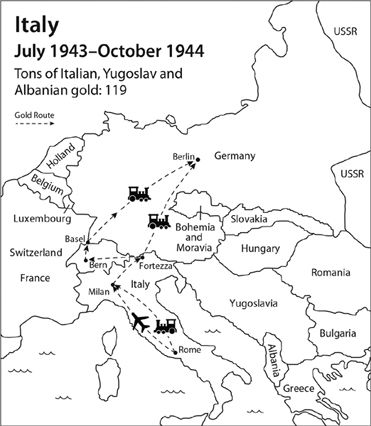

Chapter Twenty-Five

DRAGGING EVERYTHING OUT ITALIAN STYLE

American and British troops scrambled ashore on the island of Sicily on July 10, 1943 to begin the British and American attempt to recapture the European mainland. Churchill, who desperately wanted to go on the offensive, called the area the continent’s “soft underbelly.” Stalin had also been pressing the Americans to launch an offensive to relieve his troops on the eastern front. Only nine days later, the American air force bombed Rome, targeting a steel factory, a freight yard, and the main airport. Those blows ended Benito Mussolini’s final hold on the Italian people. The country’s Grand Council of Fascism, the party’s ruling body, on July 25 voted no confidence in him and asked King Victor Emmanuel to resume his full constitutional powers as leader of the country. Later that day, the king ordered Il Duce arrested. Following the fall of the Italian leader, the Nazis quickly moved ten divisions into Italy to shore up the country in anticipation of an Allied invasion of the mainland.

1

1

Italian military units moved Il Duce around the country after his arrest and eventually imprisoned him in the Campo Imperatore Hotel at Gran Sasso d’Italia in the Apennine Mountains about eighty miles north of Rome. He did not stay there long. On September 12,

SS

Lt. Colonel Otto Skorzeny led a Nazi commando unit in gliders that landed near the resort and without firing a single shot overwhelmed 200

carabinieri

guards. Skorzeny told Mussolini, “The Führer has sent me to set you free!” Mussolini replied: “I knew that my friend would not forsake me!”

2

SS

Lt. Colonel Otto Skorzeny led a Nazi commando unit in gliders that landed near the resort and without firing a single shot overwhelmed 200

carabinieri

guards. Skorzeny told Mussolini, “The Führer has sent me to set you free!” Mussolini replied: “I knew that my friend would not forsake me!”

2

The Germans immediately took Mussolini to Berlin, where Hitler was appalled by his one-time mentor’s physical and emotional deterioration. Nonetheless, the Führer made him the leader of a new puppet state called the Italian Social Republic. Its nominal capital was Rome, but that was too close to the invading forces so it operated out of the town of Salò on Lake Garda in northern Italy. Mussolini was now the total tool of Hitler.

Early in the war, the Italian fascist government had undertaken a study to find a central location in the country where its bullion could be easily protected. At the time it was located at the

Banca d’Italia

(Bank of Italy) headquarters in Rome at the Palazzo Koch, a palace on Via Nazionale. Mussolini selected the small town of L’Aquila, which was in a narrow valley about sixty miles northeast of Rome. The government began printing paper currency there, but the gold was never moved. With the war going badly for the Italian fascists, officials decided to look for another location. The country’s finance minister argued that it should go to the mountainous Trentino-Alto Adige region north of Venice. Before that could be accomplished, however, Mussolini was ousted. Bank governor Vincenzo Azzolini suggested distributing the bullion among several cities around the country to reduce the risk that the Allies would capture it intact. Marshal Pietro Badoglio, the head of the military, wanted it sent to an Italian bank near the Swiss border, but that too was nixed.

3

Banca d’Italia

(Bank of Italy) headquarters in Rome at the Palazzo Koch, a palace on Via Nazionale. Mussolini selected the small town of L’Aquila, which was in a narrow valley about sixty miles northeast of Rome. The government began printing paper currency there, but the gold was never moved. With the war going badly for the Italian fascists, officials decided to look for another location. The country’s finance minister argued that it should go to the mountainous Trentino-Alto Adige region north of Venice. Before that could be accomplished, however, Mussolini was ousted. Bank governor Vincenzo Azzolini suggested distributing the bullion among several cities around the country to reduce the risk that the Allies would capture it intact. Marshal Pietro Badoglio, the head of the military, wanted it sent to an Italian bank near the Swiss border, but that too was nixed.

3

At a meeting of the Bank of Italy’s board on July 28, Azzolini pushed through a plan to move the bullion out of Rome, although the destination was still not clear. Less than two weeks later on August 10, 1943, the banker met with General Badoglio to work out the details. The actual creation of the plan went slowly. At one point in September, there was even a proposal to ship the bullion to Sardinia, which the British and Americans had already liberated. Finally the general told Azzolini that he and other bank officials should work out a plan to move it north by train.

Other books

Strange is the Night by Sebastian, Justine

I Don't Have a Happy Place by Kim Korson

The Pearl at the Gate by Anya Delvay

My Fair Temptress by Christina Dodd

Posey (Low #1.5) by Mary Elizabeth

Beyond Squaw Creek by Jon Sharpe

Captured by a Laird by Loretta Laird

Veganomicon: The Ultimate Vegan Cookbook by Isa Chandra Moskowitz, Terry Hope Romero

The Doctor Digs a Grave by Robin Hathaway

Junie B. Jones Is (Almost) a Flower Girl by Barbara Park