Chasing Gold: The Incredible Story of How the Nazis Stole Europe's Bullion (56 page)

Read Chasing Gold: The Incredible Story of How the Nazis Stole Europe's Bullion Online

Authors: George M. Taber

BOOK: Chasing Gold: The Incredible Story of How the Nazis Stole Europe's Bullion

7.59Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

Plenty of Italian gold still remained in Fortezza, and Göring, as head of the Four Year Plan, insisted he needed money for “common war operations with Italy,” while the foreign minister said he needed it for “particularly secret operations of the ministry of foreign affairs.” In early January 1944, Göring proposed giving the Italian Social Republic 50 million Reichsmark ($20 million) in exchange for part of the gold. Negotiations soon began, with Mussolini and his Finance Minister Domenico Pellegrini Giampietro representing the Italian side. The Bank of Italy had no role in the talks and was not even informed that they were taking place.

An agreement was reached on February 5. Rahn signed it for the German side, while Stefiono Mussolini, the secretary general of foreign affairs, and Pelligrini Giampetro, the finance minister, endorsed it for the Italian Social Republic. The accord made “the entire amount of gold owned by the Bank of Italy available to the Ambassador and Plenipotentiary of Greater Germany in Italy.” The seventy-one tons of Italian gold was now officially in the hands of Rahn. Under a new diplomatic agreement, gold worth 141 million Reichsmark ($31.3 million), just under half the total amount, was immediately handed over to Berlin as a “contribution to the joint war effort.” In addition, gold valued at 250 million lira ($12.5 million) was given in “restitution” for the Yugoslav gold, 100 million lira ($3.3 million) went to the German foreign ministry to pay for its undercover operations abroad, and 50 million lira ($2.5 million) was used to settle a Nazi claim against the Italian state. Azzolini did not even learn of the agreement until three weeks after it was signed. The 50.5 tons of gold in 175 sealed boxes and 435 sealed bags left Fortezza on February 29 and arrived in Berlin three days later.

16

16

When German officials inspected the Fortezza gold, their calculations turned out to be significantly lower than the Italy’s because various boxes or bags did not contain as much metal as was listed. The total shipment was nearly a ton short. The bulk of the gold was nonetheless sent immediately to the Reichsbank since it still had the safest vaults in Berlin. One hundred thirty-five sacks with a combined weight of just over eight metric tons, though, were given directly to the foreign ministry. Ribbentrop was so anxious to get his gold that he sent one of his own officials to meet the train at the Berlin station. He also wanted to make sure he got coins denominated in dollars, francs, and other currencies, which would be easy for foreign ministry agents to use in their secret operations. Ribbentrop also took a few bars.

Shipping the last Italian gold to Berlin dragged on for many months. Some Italian officials such as Finance Minister Pellegrini Giampietro were willing to hand over the remaining bullion. Others, including Azzolini, were now trying to separate themselves from the gold deliveries to Berlin and from Mussolini’s republic, which seemed to be on the losing side of the war. In May 1944, the Nazis were back demanding that 21.5 metric tons still stored in Fortezza be shipped to Berlin. This time the Reichsbank’s Maximilian Bernhuber handled the negotiations for the Germans, while Azzolini opened them for the Italians. Both he and his successor in the gold talks, Giovanni Orgera, procrastinated, but finally the irate Finance Minister Pellegrini Giampietro ordered the central bank to hand over the bullion.

On October 21, 1944, the Italians shipped to Berlin 153 barrels and 53 bags of gold coins, weighing in at 21.5 tons. It arrived four days later. That brought the total amount sent in two consignments to 71 tons, but that was still a ton less than the amount recorded by the Bank of Italy. The Germans were beginning to notice that Italian deliveries were always a little lighter than the declared weight, which they passed off as simply Latin inefficiency. From the second shipment, 1,607 bars were delivered to the Prussian Mint and resmelted into bars that were given German identification marks. Another 141 were sent to the Degussa company for refining and made into bars. In total, the Bank of Italy sent 69.3 tons of its own gold to Berlin, in addition to 8.3 tons of Yugoslav bullion and 6.6 that belonged to the Bank of France.

17

17

Following the latest shipments to Germany, there still remained in Fortezza 153 boxes and 55 sacks totaling 25 tons of gold. When American army forces liberated the area in the spring of 1945, they discovered it and turned it over to the Bank of Italy.

18

18

While the shipments were being made, Azzolini had been looking out for himself. He was able to persuade officials of both Germany and the Italian Social Republic to let him go to Rome, but then he never returned north. Rome fell to the Allies on June 5, 1944, and only two days later Italian newspapers began a campaign against him because of his role during the war. On July 10, the British interrogated him and removed him from his position at the Bank of Italy. He was also placed under house arrest. The new Italian government later charged him with collaborating with the enemy and turning the country’s gold reserves over to the Nazis. While in jail for his trial, he worked as the prison librarian. During all that time, the Reichsbank’s Puhl and the staff of the Bank for International Settlements exchanged messages lamenting his treatment and trying to figure out how to help their old friend.

19

19

Azzolini’s trial took place in three sessions between October 9 and 14, 1944. The state demanded the death penalty, but judges instead gave him thirty years in jail and required him to pay back the Bank of Italy for the losses it had suffered in its branches, which was totally unrealistic. The sentence accused him of being “significantly docile and servile toward the Nazi-fascist regime and not doing anything to save the gold when it was still possible to do so.” He remained in jail until September 1946, when the court considered a plea for amnesty. Judges that time annulled the conviction, saying that he should “cease to be condemned and penalized further.” The judges even praised him, writing, “All the behavior of Azzolini revealed not a willingness to favor the gold plundering by the Germans, but actually an opposing willingness to resist them, using all the shrewdness that the time and the circumstances allowed him to use.”

20

20

While the Nazi regime was concentrating on capturing the Bank of Italy’s gold, the Nazi

SS

went after smaller amounts held by Rome’s 12,000 Jews.

SS

Lt. Colonel Herbert Kappler on September 26, 1944 ordered two of the community’s elders to collect 50 kilos of gold within thirty-six hours. He warned them that if they failed, he would arrest two hundred Jews and send them to the Russian front. Roman Jews reached into their family treasures and also turned in gold from synagogues. When Pope Pius XII heard about the demand, he authorized Catholic churches to make loans of gold to the Jews to help them reach their absurdly high quota. The bullion was quickly collected, although the elders said they were having difficulty raising the amount out of fear that if they said they had it, the Germans would simply ask for more. They ultimately assembled 80 kilos but delivered only 50.3, holding back the rest for later use. An

SS

Captain at first incorrectly weighed the metal and then lashed at the Jews for not turning over enough. A second weighing showed that they had slightly more than demanded.

21

SS

went after smaller amounts held by Rome’s 12,000 Jews.

SS

Lt. Colonel Herbert Kappler on September 26, 1944 ordered two of the community’s elders to collect 50 kilos of gold within thirty-six hours. He warned them that if they failed, he would arrest two hundred Jews and send them to the Russian front. Roman Jews reached into their family treasures and also turned in gold from synagogues. When Pope Pius XII heard about the demand, he authorized Catholic churches to make loans of gold to the Jews to help them reach their absurdly high quota. The bullion was quickly collected, although the elders said they were having difficulty raising the amount out of fear that if they said they had it, the Germans would simply ask for more. They ultimately assembled 80 kilos but delivered only 50.3, holding back the rest for later use. An

SS

Captain at first incorrectly weighed the metal and then lashed at the Jews for not turning over enough. A second weighing showed that they had slightly more than demanded.

21

The gold was shipped to

SS

headquarters in Berlin addressed to

SS

General Ernst Kaltenbrunner, Himmler’s deputy. Kappler included with it a letter reminding the general of the plan to use Jews in Rome as laborers. He received back a strong rebuke saying that the Nazi objective was “the immediate and thorough eradication of the Jews in Italy.” A roundup soon followed. At the end of the war, Allied soldiers found the crate of Jewish gold from Rome still unopened in Kaltenbrunner’s office.

22

SS

headquarters in Berlin addressed to

SS

General Ernst Kaltenbrunner, Himmler’s deputy. Kappler included with it a letter reminding the general of the plan to use Jews in Rome as laborers. He received back a strong rebuke saying that the Nazi objective was “the immediate and thorough eradication of the Jews in Italy.” A roundup soon followed. At the end of the war, Allied soldiers found the crate of Jewish gold from Rome still unopened in Kaltenbrunner’s office.

22

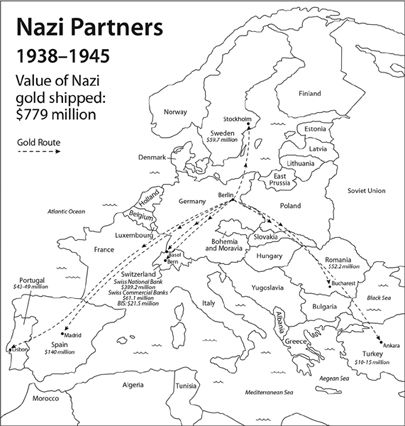

Chapter Twenty-Six

PARTNERS IN GOLD

Without the help of a few key co-conspirators, the gold the Nazi regime seized from invaded countries would have simply sat untouched and gathering dust in the Reichsbank vaults. It would not have played a major role in helping Hitler achieve his war objectives. Because of those partners, however, Germany was able to turn the stolen bullion into an important tool for waging World War II. A few nominally neutral countries were willing to turn stolen bullion into currencies that could be used to buy crucial war materiel. Without Romanian oil, Portuguese and Spanish tungsten, Turkish chromium, Swedish iron ore, and a few other items, along with key countries such as Switzerland that were willing to facilitate the sales, the German war machine would have ground to a halt long before May 1945. German leaders at the apogee of their power in 1941 were confident that they would continue conquering countries and eventually hold most of the world’s gold. The Reichsbank’s Walther Funk in a speech in Rome on October 20, 1940, said categorically, “By the end of the war, the gold which we need will be ours.”

1

1

The most important Nazi partner was Switzerland, which accepted a large amount of stolen gold. American officials with access to Reichsbank documents, calculated after the conflict was over that at least $398 million of the $579 million the Nazis stole ended up in Switzerland. Documents uncovered in a Swiss bank investigation of wartime activities confirmed that as early as June 1942, the Swiss Central Bank assumed the gold they had `received from Germany had come from occupied countries. For a while the Swiss even considered melting down bullion they had and turning it into new bars to hide its provenance.

2

2

Germany had long enjoyed strong economic and ethnic ties with its neighbor to the south. At the time of World War II, nearly three-quarters of Switzerland’s population were native German speakers, providing a strong bond between the two countries. When the Nazis in the spring of 1940 invaded Western Europe, however, Swiss leaders were terrified that their country might be the next victim. Hitler had just shown that he did not respect the neutrality of Holland or Belgium, so why would he treat Switzerland any differently? That put the small nation in a dangerous and no-win situation. If it were cozy with Berlin, London and Washington would be furious and perhaps retaliate. If it followed orders from the Allies, the Nazis would have been equally outraged and could easily occupy the country.

Switzerland was totally pro-Swiss and amoral when it came to financial transactions with the Nazis. Every nation looks out for its own self-interest. That is nothing new. What was different in World War II was that Switzerland turned a blind eye to the well-known German atrocities in order to continue its profitable financial transactions with the Nazi regime, particularly when it came to dealing in gold. For much of the war, the Swiss pedaled the idea to the Allies that it was just a poor little neutral nation being pushed around by the big, bad Nazis. In reality, it voluntarily leaned toward Germany and its golden coffers. Swiss political leaders for most of the war were only too happy to work with Berlin. The Allies made their first warning against dealing in stolen property in July 1941, but it was not until April 11, 1945, that the Swiss halted its purchases of Reichsbank gold. By then, the German defeat was obvious.

The harshest critics in recent times of Switzerland’s war record in gold transactions have been the Swiss themselves. Jean Ziegler, a professor of sociology and former member of the Swiss Confederation’s National Council, the country’s federal parliament, in 1997 published a highly critical account of his nation’s wartime activities entitled

The Swiss, the Gold, and the Dead

. In it he wrote: “Switzerland escaped World War II by virtue of shrewd, active, organized complicity with the Third Reich. From 1940 to 1945 the Swiss economy was largely integrated with the Greater German economic area. The gnomes of Zurich, Basel, and Bern were Hitler’s fences and creditors.”

3

The Swiss, the Gold, and the Dead

. In it he wrote: “Switzerland escaped World War II by virtue of shrewd, active, organized complicity with the Third Reich. From 1940 to 1945 the Swiss economy was largely integrated with the Greater German economic area. The gnomes of Zurich, Basel, and Bern were Hitler’s fences and creditors.”

3

The Swiss Independent Commission of Experts, which began an investigation of the country’s activities during the war in December 1996, finally and officially recognized the country’s complicity in Hitler’s atrocities. Nine Swiss and foreign historians plus a support staff of one hundred archivists had freedom to roam through Switzerland’s wartime records. Their final report was published in March 2002. The report was twenty-seven volumes long. Some Swiss nationalists said it did not take into account wartime conditions, but it was generally accepted as an honest and accurate study.

At the beginning of the war most of the gold transactions between Germany and Switzerland were done by private banks. The National Swiss Bank, though, took over the business in October 1941. Switzerland’s importance in the Nazi gold traffic was staggering. Three-quarters of the German bullion that was shipped abroad went through Switzerland. Between 1940 and 1945, the Nazis sold 101.2 million Swiss francs of bullion to private Swiss banks and 1,231 million through the Swiss National Bank. That was all stolen gold. The bank also dealt with Turkey, Spain, Romania, Sweden, and Portugal, which all had products the Nazis needed and would accept payment in Swiss francs.

4

4

Other books

The Scent of Sake by Joyce Lebra

The Twisted Cross by Mack Maloney

Alpha Pack 02 - Savage Awakening by J.D. Tyler

The Diamond Tree by Michael Matson

Shadow Reign (Shadow Puppeteer Book 2) by Christina E. Rundle

Peacemaker (The Flash Gold Chronicles, #3) by Lindsay Buroker

Colin's Quest by Shirleen Davies

Ride the Tiger by Lindsay McKenna

Catalyst by Viola Grace