Chinese Comfort Women (21 page)

Read Chinese Comfort Women Online

Authors: Peipei Qiu,Su Zhiliang,Chen Lifei

Tags: #History, #Military, #World War II, #Modern, #20th Century, #Social Science, #Women's Studies

Life became even more miserable after I became pregnant. I realized I would die sooner or later as a result of the abuse by the Japanese soldiers, but I didn’t want to die. My parents were still alive and they needed me to take care of them. I secretly talked to another Hubei girl whom the Japanese troops called “Rumiko,” and we planned to escape. However, we were caught as soon as we ran out. A Japanese soldier held my hair and violently hit my head against the wall. Blood immediately gushed out. The beating left me with incurable headaches; I still suffer from them to this day. [Yuan Zhuling had a miscarriage and because of that she was unable to bear a child for the rest of her life.]

From the first days when I was imprisoned in the comfort station, a Japanese military officer named Fujimura took a fancy to me. He was probably the head officer of the Japanese army stationed in Ezhou. At the beginning he bought tickets to visit the comfort station, as the other Japanese soldiers did, but after a while he requested instead that the proprietor send me to the place where he lived. Compared with the conditions in the comfort station, life conditions at Fujimura’s house were better, but I was still the officer’s slave with no freedom. After a while Fujimura lost interest in me. At that time a lower-ranking officer named Nishiyama seemed to be rather sympathetic toward me, and he asked Fujimura to give me to him. I was then taken to where Nishiyama’s troops were stationed. This was quite an unusual experience, which, to this day, makes me believe that Nishiyama was a kind person.

Around 1941, I obtained Nishiyama’s permission to return home to visit my parents, only to find that my father had already died. My father had worked as a labourer. Because he was a small man and very old, he was frequently fired and had difficulty finding another job. He starved to death. I went to look for Liu Wanghai, but couldn’t find him either. I had no place to go, so I returned to Ezhou, where Nishiyama was.

The Chinese War of Resistance against Japan ended in August 1945. Nishiyama asked me to go with him, either to Japan or to Shihuiyao, a place that was then under the control of the New Fourth Army.

4

I did not go with him because I wanted to find my mother. [Yuan Zhulin stopped talking at this point and heaved a deep sigh.] Nishiyama was a good man. He served in

the Japanese army, but he didn’t take advantage of his position to extort money. The shirt he wore was torn and ragged. He told me that he had once made a hole in a ship that was carrying supplies to the Japanese army and sank it. And when he saw Japanese troops electrocuting Chinese people who sold salt illegally, he felt sympathetic and he gave packages of salt to the Chinese people. [The Japanese military imposed strict control over the market during the war. Free purchase of salt was prohibited in some occupied areas.] Nishiyama left alone and I haven’t heard from him since.

[Yuan didn’t know whether Nishiyama had returned to Japan or had gone to Shihuiyao. She inquired about his whereabouts over the years with no results. Later, however, during the political turmoil in China, Yuan’s relationship with the Japanese man brought her more hardship.]

After the Japanese surrender, I found my mother and went to live with her in her hometown, a small mountain village in the vicinity of Wuhan. We worked as day labourers to support ourselves. In 1946, I adopted a girl who was only a little over two months old. I named her Cheng Fei.

I returned to Wuhan after the Liberation in 1949 and lived at Number 2 Jixiangli. One day I saw Zhang Xiuying, the woman who had tricked me and the other girls into the living hell. Zhang was running a shop with an old man at the time. I immediately reported her to the local policeman in charge of household registration. I still remember that policeman’s last name – Luo. But Officer Luo said: “Forget it. Those things are hard to investigate.” His words chilled my heart as if it were doused with ice water. Zhang Xiuying has probably died by now.

Although deep in my heart, memories of my horrific past have always haunted me and caused me sleepless nights, my life with my mother was relatively peaceful. But, one day at a meeting called “Tell Your Sufferings in the Old Society and the Happiness in the New” (

yi ku si tian

) my naïve mother talked about my miseries when I was forced by the Japanese army to be a military comfort woman. This caused us big trouble. Children in the neighbourhood chased me, shouting: “A whore working for the Japanese! A whore working for the Japanese!”

In 1958, the Neighbourhood Committee officials accused me of having been a prostitute working for the Japanese,

5

and they ordered me to go to the remote northern province of Heilongjiang. I refused to go. The head of the Neighbourhood Committee then deceived me by saying that they needed my residence booklet and food purchase card for a routine check. They took these documents and revoked them. The policemen in charge of household registration then ordered me to reform through hard labour in the countryside. We were forced to move to Heilongjiang. My house was confiscated.

We spent the following seventeen years in Mishan [in Heilongjiang Province, northeast China] doing farm work, such as planting corn and harvesting soybeans. The weather was very cold there and we didn’t have any firewood with which to warm ourselves. Each month we only got six

jin

[1

jin

equals 0.5 kilograms] of soybean dregs to eat. [Soybean dregs are the solids left after the oil is extracted from soybeans, which are normally used to feed horses and cows, etc.] My adopted daughter was so hungry that she would grab dirt and eat it. We suffered all kinds of hardship. Luckily there was a section chief named Wang Wanlou who felt very sorry for how we suffered, so he helped us obtain permission to return to Wuhan. That was in 1975. I will be forever grateful for his kindness.

Today I am receiving 120 yuan [about fifteen dollars at the time] in monthly support from the government. My adopted daughter gives me 150 yuan every month, but she is retired, as am I. My health has long been destroyed. Because of the beatings by the Japanese soldiers, I have headaches every day that cause me difficulties sleeping. Even after taking many sleeping pills, I still cannot sleep more than two hours. For the remainder of the night, I sit in pain waiting for daybreak.

[At the end of the interview, Yuan Zhulin cried.]

My life was destroyed by the Japanese military. My first husband and I would never have been parted if there hadn’t been the Japanese invasion. I have nightmares every night. In the nightmares I see myself suffering in that horrible place, suffering miseries beyond human imagination.

I am now seventy-nine years old. I don’t have many years left. The Japanese government must pay compensation for our sufferings. I don’t have time to wait any longer.

Yuan Zhulin moved to Zhanjiang City, Guangdong Province, to live with her adopted daughter in January 2006; she could no longer live alone due to old age and poor health. Two months later she suffered a stroke and died in hospital at the age of eighty-four. Chen Lifei and Yao Fei, from the Research Centre for Chinese “Comfort Women,” attended the ceremony at which her ashes were laid to rest

.

(Interviewed by Su Zhiliang in 1998 and 2001)

Tan Yuhua

Between 29 September and 6 October 1939 Japanese forces suffered a major defeat in Hunan Province south of Hubei

.

6

Chinese Nationalist soldiers fought fiercely to stop the advance of the Japanese army and, from 1939 to 1944, engaged in four major battles to defend the provincial capital, Changsha. In order to control Hunan, the Imperial Japanese Army deployed ten divisions with about 250,000 to 280,000 soldiers to the battle in 1944

.

7

During approximately five years of fighting in the area Japanese troops established a large number of comfort stations. Tan Yuhua’s hometown in Yiyang County, Hunan Province, was occupied by the 40th Division of the Japanese army in June 1944, a few days before the City of Changsha fell to the Japanese

.

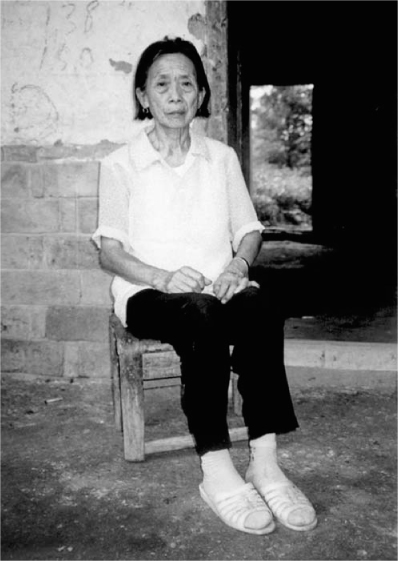

Figure 13

Tan Yuhua, in 2008, in front of her home.

My original name was Yao Chunxiu. I was born in the Seventeenth Year of the Republic of China [1928] in Yaojiawan, Shilang Township, Yiyang County, Hunan Province [today’s Yaojiawan Group, Gaoping Village, Town of Oujiangcha, Heshan District, Yiyang City]. My father, Yao Meisheng, was a villager, but he was unable to do farm work due to his disabled legs, so he made a living as a craftsman, making bamboo items. My mother did not have a formal name; people called her “Yao’s wife.”

I was the only girl in the family, so my parents let me attend school for fun with my cousins. I attended a private village school for a few years. I still remember that our teacher was Mr. Yuan; he later stopped teaching after the Japanese troops occupied our area. I learned how to read

Zeng guang xian wen

8

and

You xue qiong lin

,

9

but I’ve forgotten most of the characters I learned.

The Japanese troops came to my hometown in the Thirty-Third Year of the Republic of China [1944], when I was sixteen. Local people all fled. That day I was having my supper when I heard the neighing of horses and braying of donkeys at the riverside. I saw the Japanese troops crossing the Dazha River, marching in our direction, and creating an air of terror. We were frightened and ran away, but my father was unable to run with us because his legs hurt. My mother, uncle, cousin, and I ran without stopping until we reached the Fumen Mountains sixty

li

[thirty kilometres] away, where there were no Japanese soldiers around. We stayed at my aunt’s house for about half a year. During the Japanese occupation local people always helped each other, kindly providing food and lodging to others who had fled from Japanese attack.

I remember that, when we ran away, we were still wearing over-jackets, and it was already around the Eighth Lunar Month when we returned home. We heard that the township formed an Association for Maintaining Order run by local people, so we thought that order had been restored and that it would be safe to return home. People who had stayed in the area told me the Japanese troops had burned houses and randomly opened fire in Zhuliangqiao.

10

They set fire to houses one after another. Many houses had thatched roofs at that time so they were easily burned down.

My family had a tile-roofed house so it was not burned. Our house was across the road from Zhuliang-qiao, where the Japanese soldiers often fired their guns. We placed a large table in the central room and covered it with a cotton-padded quilt. When we heard the gunfire we would hide under the table watching the soldiers passing by my house.

The Japanese soldiers were stationed in Zhuliang-qiao and also on Shizishan Mountain about one

li

away from Zhuliang-qiao. On top of the mountain

the Japanese troops built a lookout tower, which was constructed of wooden boards mounted to three big camphor trees. A guard standing on the tower could keep watch over the entire town of Zhuliang-qiao. The Japanese soldiers made a tunnel, and they went back and forth through it to Zhuliang-qiao.

One day I saw the Japanese soldiers capture a villager named Qiu Siyi, tie him to a wooden frame, and let an army dog maul him to death. The Japanese army dog was huge; it looked like a wolf. I also saw a woman captured by the soldiers, but I didn’t know her name. She had attempted to escape but failed; the Japanese soldiers buried her alive. Another girl who was also buried alive looked very young, like a teenager. A soldier shovelled dirt onto her body; he stopped in the middle of his task and laughed until she died. I didn’t know the girl’s name.

My cousin was married right after we returned to our village in the Eighth Lunar Month, and soon after that I was married, too. Fearing the chaos of the war, our parents urged us to get married as soon as possible. However, fewer than twenty days after my wedding, I was kidnapped by Japanese troops. It was in the Ninth Lunar Month when the weather was not yet very cold. I was so frightened at the time that I cannot clearly remember what happened. I don’t know the exact date and time, but I remember that I was wearing a single-layer coat. The Japanese troops came from the other side of the river, not from Zhuliang-qiao, so we didn’t notice them approaching the town and were unable to run away in time.

The Japanese soldiers caught my crippled father first. They made him kneel down, and a soldier threatened to kill him with a long curved sword. I couldn’t help crying out, so the Japanese soldiers found and caught me. The soldiers also captured two other girls, Yao Bailian and Yao Cuilian, both of whom were my cousins and schoolmates; both were older than I. One of my aunts died during that attack. The soldiers arrested my father to force him to work for them, but my father was unable to perform hard labour due to his disability so the Japanese soldiers killed him. I lost my father forever.