Chinese Comfort Women (23 page)

Read Chinese Comfort Women Online

Authors: Peipei Qiu,Su Zhiliang,Chen Lifei

Tags: #History, #Military, #World War II, #Modern, #20th Century, #Social Science, #Women's Studies

This situation lasted for two full years until I turned twenty-one. By that time I had become very sick. I suffered from constant dizziness and body aches as well as from a menstrual disorder. My sister was also raped by the Japanese soldiers. She was carried to the blockhouse and held there for a long period of time. We often bemoaned our fate, wondering, “Why us?” In order to escape the horrible situation I tried to remarry, but everyone knew that I had been raped by Japanese soldiers, and no man in the region wanted to marry me. Knowing that it was impossible to find a man in Yu County who would marry me, I married a man named Yang Erquan in distant Zhengjiazhai Village in Quyang County and finally escaped the misery.

My second husband was the same age as I. He was a shepherd, a very honest person. His family was poor but I did not mind; he did not look down on me either. Indeed, he was a really nice person. We helped each other in our poor life. The torture of the Japanese soldiers damaged my health. In order to cure my uterine damage my husband took on several hard jobs simultaneously for many years to earn money for my treatments. He peddled goods and also cleaned cesspools to earn some millet, and then he sold the millet to make some money. He encouraged me, saying, “You will get better.” I wanted to repay him for his kindness and to be able to have children with him, so I did my part, too, and sought treatment. I was so happy when I finally became pregnant and gave birth to a son at age thirty-three. Later, I gave birth to a girl.

China won the Resistance War, and the Japanese troops fled back home in 1945. However, my misery did not disappear with them. Although I was able to bear children, my uterine damage was never completely cured. It has bothered me for more than fifty years. Sometimes it is better, sometimes worse, with a filthy reddish discharge. My husband worked too hard and damaged his own health as a result. He died in 1991. I was deeply saddened.

My sister has suffered even more than I have. She was not able to have children because of the torture, so she was abandoned by her husband and she had to remarry twice. At this time both my sister and I still suffer from severe uterine damage. Our lower bodies hurt constantly, which makes every movement very difficult. My health has been declining in recent years. The lower back pain that has bothered me for years has become worse, as has the trembling in my hands and legs. I am also suffering from acute psychological problems, such as intense fear and nightmares in which I relive those past experiences. I am trembling right now as I recall the past horror. These

unspeakable things are really hard to talk about, but I can no longer keep silent. If I don’t speak out, people will not know how evil those Japanese troops were.

I am now living with my son and daughter-in-law. After I die they will continue to fight for justice. Generation after generation we must continue fighting those who deny the Japanese troops’ atrocities, until they admit them!

In 2001, the Shanghai TV Station and the Research Center for Chinese “Comfort Women” jointly produced a documentary entitled

The Last Survivors (Zuihou de xingcunzhe),

which records Yin Yulin’s life story. On 6 October 2012, Yin Yulin died in her cave dwelling after the life-long suffering

.

(Interviewed by Su Zhiliang and Chen Lifei in 2000 and 2001)

Wan Aihua

After the Hundred Regiments Offensive the Japanese army increased the number of its strongholds to twenty-two in Yu County

,

17

and it continued waging fierce campaigns to wipe out the resistance, while the Chinese forces continued fighting back and mobilizing local villagers. Wan Aihua, who participated in the resistance movement, was captured by the Japanese troops during these mop-up operations

.

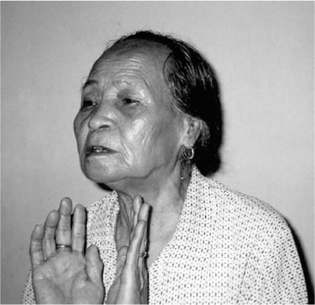

Figure 15

Wan Aihua, in 2000, telling the students and faculty at Shanghai Normal University how she was tortured by Japanese soldiers during the war.

I was born in Jiucaigou Village, Helingeer County, Suiyuan Province [today’s Inner Mongolia] on the Twelfth Day of the Twelfth Lunar Month in 1929. My original name was Liu Chunlian.

18

My father was named Liu Taihai and my mother Zhang Banni. I had an older brother, a younger brother, and two younger sisters. My father was addicted to opium and he spent all of our money on it, leaving my family destitute. My mother gave birth to my younger brother when I was about four years old. Unable to support so many children, my father decided to sell me. My mother wailed aloud and she repeated to me my birth date, my parents’ names, and home village until I was able to

remember them. I was taller than most girls of my age, so my father was able to sell me to the human trafficker as an eight-year-old. After that traffickers traded me again and again, and each time the trafficker increased the price. Eventually, I was sold in Yangquan Village in Yu County and became Li Wuxiao’s child-bride.

19

Three other girls were sold in that village at the same time, but I was the only one who survived. Life was extremely hard, as was survival, in those days. My name was changed to Lingyu in Yangquan Village. I learned to do the work expected of a child-bride, and, growing up in hardship, I became a big, strong girl.

In 1938 the Japanese invaders entered Yu County, where the Japanese army ordered the local collaborators to form an Association for Maintaining Order and a puppet county government. In the spring of the following year, the Japanese troops built strongholds and blockhouses in the county seat, Donghuili, Shangshe, Xiyan, and other villages and towns. I hated the Japanese troops for the atrocious things they did to the Chinese people, so I followed the Chinese Communist Party [CCP] and actively participated in the resistance movement. I was among the first to join the Children’s Corps and was elected the leader. Although I was still a child, I was tall in stature and had always worked with adults. Soon I became a CCP member through the recommendations of Li Yuanlin and Zhang Bingwu.

20

The people with whom I worked were deeply sympathetic to me because of what I had experienced at such a young age. Liu Guihua, Commander of the 19th Regiment of the Eighth Route Army, renamed me Kezai [The two characters in Chinese mean “to overcome misfortune”] to wish me smooth sailing in life. I worked very hard and served as a member of the CCP branch committee in Yangquan Village, which at that time was called “lesser district committee,” and I also served as deputy village head and director of the Women’s Association for Saving the Nation. My CCP membership was kept secret, and my activities were underground at the time so that the collaborators and the Japanese troops would not know.

Japanese troops set up strongholds in Shangshe, Jinguishe, and other places once they occupied Yu County. In the spring of 1943, I remember it was the season when plants just begin to grow in the yard, Japanese troops stationed at Jinguishe carried out a mop-up operation in Yangquan Village. My father-in-law was over seventy years old at the time and he was sick with typhoid. Although I was a child-daughter-in-law in the family, he had always treated me with kindness, so I didn’t want to leave him behind to flee with the other villagers. The Japanese soldiers caught me.

The Japanese troops took all their captives to the riverbed. They announced that I was a member of the Communist Party. As a Japanese officer was about

to kill me, an aged man in the village knelt down and begged him to spare me. He said that I was only a child and that I was a dutiful daughter to my parents-in-law, not a communist. The interpreter held the arm of the Japanese captain who had drawn his sword and translated the old man’s words to him. That captain was a very cruel person and had buckteeth, so the villagers called him “Captain Donkey.” Captain Donkey put his sword back after he heard the interpreter’s words. I am forever grateful to that old man and to the interpreter. I didn’t know if the interpreter was Japanese, but I believe there were kind people in the Japanese troops, just as there are today, when many Japanese people support our fight for justice.

The Japanese soldiers took me and the other four girls back to the Jingui stronghold. Jingui was a small village in the mountains. After the Japanese army occupied the area they built a blockhouse on top of the mountain, forced the villagers who lived in the cave dwellings in the surrounding area to move away, and confiscated their dwellings. The other four girls and I were locked in these caves. In the cave there was a mat, made of sorghum stalks, on the ground. A quilt, a pillow, and a blanket were put on the mat. I was not allowed to go out even when I needed to relieve my bowels. At the beginning of my captivity I still had the strength to empty the excrement pail but soon became too weak to do so.

Because a traitor revealed my anti-Japanese activities to the Japanese troops, they treated me more viciously than they did the other girls. During the daytime the Japanese soldiers hung me up on a locust tree outside the cave and beat me, forcing me to admit I was a communist and to tell them who else in the village were CCP members. I gritted my teeth tightly and refused to say anything. At night the Japanese soldiers locked me in the cave room and gang-raped me. The torture damaged my head, so I don’t remember the details clearly now. I only remember that I was imprisoned there for days. I knew I would end up dying at the hands of the Japanese soldiers if I remained, so I planned to escape. One night when the guard wasn’t paying attention I broke out through the window and ran back to Yangquan Village. When I was kept in the military stronghold the Japanese soldiers had local people deliver food to us. One of the deliverymen, named Zhang Menghai, saw how I was confined in the cave and what was done to me. According to him, I escaped from captivity by breaking the window lattice, which was in poor shape.

I still remember the quilt I used while in the cave. I knew the quilt had belonged to a villager named Hou Datu, who was my co-worker and a core member of the local resistance movement. Hou Datu is now over seventy years old and still lives in Xiangcaoliang Village on the other side of the

mountain. Li Guiming knows this man.

21

Young people call him “Uncle Datu.” I had seen this quilt when I visited Hou’s house previously, so I knew it must be one of the things the Japanese troops had plundered during their mop-up operations. The cover of the quilt had a nice pattern, so I remembered it clearly. I tied up the quilt, the pillowcase, and the blanket and took them with me when I escaped. While escaping I ran into three village resistance movement leaders who were on their way to rescue me. They were surprised to see that I had already broken out from the confinement by myself. I asked the village leaders to return the bedding to Hou Datu. [Su Zhiliang and Chen Lifei spoke to Hou Datu on 11 August 2000 and verified what Wan Aihua said. Hou was seventy-four at the time of the interview, and he clearly remembered the Japanese army’s torture of Wan Aihua. He was the only one still alive who had witnessed Wan Aihua’s experience as the Japanese army’s sex slave.]

When I got back to my home village, my husband-to-be, Li Wuxiao, wanted to cancel our marriage engagement because I had been raped by Japanese soldiers. A man called Li Jigui, who was also a resistance movement activist in the village and much older than I, was willing to help me out. However, Li Wuxiao asked him to pay for my release. With the help of the village head, Li Jigui paid Li Wuxiao dozens of silver dollars and took me home. Li Jigui married me and paid for the treatment of my injuries.

In late summer of 1943, I was captured by the Japanese soldiers again. I remember that it was when watermelons were ripe and many people were selling them. I was washing clothes by a pond when I heard someone shouting, “Japanese devils are here!” Before I turned around to run, a Japanese soldier grabbed my hair, and I was kidnapped by the Japanese troops yet again. This time a large number of Japanese troops stationed in Xiyan Town and in Jingui came from the south and the north simultaneously and surrounded Yangquan Village. I was taken to the Jingui stronghold and subjected to more brutal torture. The Japanese soldiers pulled one of my earrings off, tearing off part of my earlobe with it.

The Japanese soldiers raped me day and night. Sometimes two or three soldiers entered the room together and gang-raped me. They beat and kicked me when I resisted, leaving wounds all over my body. Later the soldiers came less often at night, perhaps disgusted at the purulent wounds on my body. The torture lasted for about half a month, until one night I found the blockhouse strangely quiet. “The devils must have gone on another mop-up action,” I thought, “It appears there are not many soldiers here.” I quietly jacked up the door and crawled out.

I was so weak that I had to rest many times when I was running away. I dared not return to Yangquan Village, so I ran to Xilianggou Village, where my

ganma

lived. [In China, people who are particularly fond of each other can form a fictive kinship and call each other by kinship terms plus the term “gan,” such as

ganma

(fictive mother),

ganerzi

(fictive son),

ganjiejie

(fictive older sister). The relationship is only in name and the fictive child usually does not move in with the ganma’s family and is not raised by her.] My

ganma

’s family name was Wan. She had five sons; all of them were good men who had joined the Communist Party. Unfortunately, they have all died now. I hid at the Wans’ house for about two months and, when my injuries healed, returned to Yangquan Village. My husband Li Jigui was sick in bed when I saw him; he was only skin and bones. I devoted all my time to taking care of him.