Chinese Comfort Women (19 page)

Read Chinese Comfort Women Online

Authors: Peipei Qiu,Su Zhiliang,Chen Lifei

Tags: #History, #Military, #World War II, #Modern, #20th Century, #Social Science, #Women's Studies

A kind man in the village, Mr. Jiang, often helped me with heavy work after my husband left home. He was thirteen years older than I and was not married due to the lack of money. In 1943 he proposed to me. We were married that year and had a son a year later. We named our son Jiang Weixun.

After the establishment of the People’s Republic of China, my first husband, Ni Jincheng, was granted military honours. When my second husband died, I told my son and grandchildren about my painful past. I also told them that I had married twice and how my first husband joined the resistance forces and fought to his death against the Japanese troops. I wanted them to remember who had committed the atrocities against me and the Chinese people.

I now live with my son, my grandson, my grandson’s wife, and my great-granddaughter. In 2007, my son read in a newspaper article that comfort station survivor Lei Guiying had died. [This is the same Lei Guiying whose narrative is presented earlier.] He also learned that the Japanese high court had just rejected two cases filed by former Chinese labourers and comfort women. I cried when my son told me that. I respected Lei Guiying, who had the courage to reveal her experiences to the world and to testify on behalf of all the comfort women. The Japanese government refuses to take responsibility for the crimes Japanese soldiers committed against Chinese women during the war, but I can be one of the witnesses. I let my son send letters to people telling of my experience in the comfort station. [Jiang Weixun sent the letters to Rugao City Women’s Federation, the Association for Research on the Nanjing Massacre, and the Jiangsu Province Academy of Social Sciences.] My son told me that the right-wing activists in Japan want to cover up the crimes committed by the Japanese military, but we cannot let them have their way. Although Lei Guiying died, I will continue her efforts.

One year after she revealed her experience in the Japanese military comfort station to the public, Zhou Fenying died on 6 July 2008 at her home in Yangjiayuan Village, Rugao County

.

(Interviewed by Su Zhiliang and Chen Lifei in October 2007)

Zhu Qiaomei

On 18 March 1938, three months after the Nanjing Massacre, Japanese forces landed on Chongming Island, which is located at the mouth of the Yangtze River near Shanghai. The island, from a military perspective, was an important geographical position. Two Japanese warships and five combat planes covered the landing and the occupation forces stationed in each of the four major towns on the island. One month later, three hundred additional Japanese troops from Shanghai and Ningbo were assembled on Chongming. Wang Jingwei’s puppet government also sent security troops to the area from Shanghai

.

6

Although, after the outbreak of war on the Pacific front in 1942, some troops were dispatched to the battlefronts at Burma, Singapore, and elsewhere, a large number of troops remained on Chongming Island until Japan’s surrender in 1945. Many local women were assaulted and abducted into the military comfort stations during the Japanese occupation. Zhu Qiaomei and Lu Xiuzhen were both forced to serve as Japanese military comfort women on Chongming Island

.

7

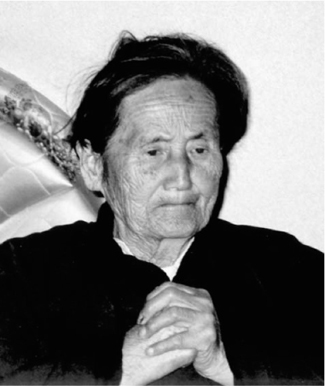

Figure 10

Zhu Qiaomei at the 2001 notarization of her wartime experiences.

My name is Zhu Qiaomei. Because my husband’s last name was Zhou, I was also called Zhou Qiaomei, or Zhou Aqiao [“Aqiao” is her nickname.] I was born in Ximen of Xiaokunshan in Songjiang County, Shanghai, in the Year of the Dog and am now ninety-one years old.

In my youth I was a bookbinder working at Commercial Press in Shanghai; I married Zhou Shouwen in 1928. In 1932, the Japanese forces bombed the Commercial Press building so I lost my job and fled to Chongming with my husband. From that time on we never left Chongming. We settled in Miaozhen Town and opened a little restaurant named “House of Eternal Prosperity” (Yongxing guan). Our restaurant was not big and mainly served cold dishes and light refreshments, but the business was good. My husband and I had a very good relationship, so we lived a quiet and sweet life. In July 1933, I gave birth to my second son, Zhou Xie.

In the spring of 1938 the Japanese army occupied Chongming and Japanese troops built a blockhouse at Miaozhen, where one company of Japanese soldiers was stationed. The remains of that building were torn down a few years ago. Japanese troops constantly came out to assault the village people. We didn’t have anywhere to run to, so we stayed in our little restaurant. One day, several Japanese soldiers dashed into our restaurant, wearing yellowish uniforms and holding long rifles. They forced all of the customers to leave and raped me in a locked room. At that time I was two or three months pregnant with my third son, Zhou Xin.

The Japanese unit,

8

whose name I think was “Songjing Company” [“Songjing” is written in two characters, which are read as “Matsui” in Japanese], lived in a two- or three-story building.

9

I remember that people called the unit head “Senge,” and the head of a squadron “Heilian” [These names are hard to reconcile because they do not seem to be the pronunciations of the characters used in common Japanese names; the local people may have pronounced the names incorrectly], and there was an interpreter. They searched high and low for good-looking women to “comfort” the Japanese officers. In order to meet the desires of the Japanese officers, they forced seven towns-women to form a “comfort woman group.” These “Seven Sisters” were Zhou Haimei (Sister Mei), Lu Fenglang (Sister Feng), Yang Qijie (Sister Qi), Zhou Dalang (Sister Da), Jin Yu (Sister Yu), Guo Yaying (Sister Ying), and me (people called me Sister Qiao). We became those Japanese troops’ sex slaves. They declared us set aside for special service to the military officers. The ordinary soldiers, who were not allowed to touch us, assaulted the other girls of the town.

The seven of us remained in our own homes. The interpreter would give us service assignments or call us to the blockhouse. Sometimes the Japanese

military officers also forced their way into our homes to rape us. If we didn’t let them, they would smash things in our houses or shops and would take out their bayonets and threatened to kill us. “Die! Die!” they yelled. The horrors were beyond human imagination.

When I was first abducted by Japanese troops I was already pregnant, but the Japanese officers raped me despite the baby in my belly. And merely two months after I birthed the child I was again subjected to frequent rapes. I had a lot of breast milk at the time, so the officers Senge and Heilian would suck my breast milk dry every time before raping me. Afraid of being killed, I had no choice but to put up with these atrocities. The Japanese troops designated a special room in their blockhouse for raping us. In the room there was only a bathtub and a bed. When we were taken in, first we had to bathe and then the Japanese military men would rape us on the little bed next to the tub. Other than that the troops never took any hygienic measures. We were almost tortured to death; no form of remuneration was ever mentioned.

This kind of torture continued until 1939. Every week I was assaulted by the Japanese troops at least five times, sometimes even more. It has been so many years now that I can’t remember the details very clearly, but I remember there were times I was taken in there and kept for an entire day and night before I was released. Let me tell you something I didn’t want to say before: among the “Seven Sisters” I mentioned earlier, Sister Mei was my mother-in-law who was already over fifty years old at the time. Those Japanese troops really sinned! Sister Feng was my mother-in-law’s younger sister who was about forty years old, and Sister Da also was a relative – a distant cousin of mine. Four in just one family suffered these atrocities; what a miserable fate!

Seeing how I was tormented by the Japanese military, my husband Zhou Shouwen chose to fight and joined the local anti-Japanese guerrilla force. But later he was seized by the Japanese troops and beaten to death. After the liberation, we found only one surviving witness who knew how he had died; this didn’t conform to government regulations, which, required at least two witnesses, so my husband didn’t earn a title of honour. How regrettable!

I was finally freed in 1939 when the Japanese troops withdrew from Miaozhen. By that time I had already developed serious venereal disease and other diseases. Today I still suffer from constant headaches, renal disorder, as well as incurable mental trauma. I am not able to free myself from mental stress, even though I never did anything of which I should feel ashamed. One thing I feel extremely bitter about is that my husband was beaten to death by the Japanese soldiers. Since his death I have been living in widowhood and have never remarried. For a long time I didn’t want to talk about what the Japanese army had done to me: it was utterly unspeakable. Now, I have only my second

son Zhou Xie and my third son Zhou Xin. I live with Zhou Xie. He is my legal representative for my lawsuit against the Japanese government. The Japanese troops were so evil; I am fighting to regain my dignity and honour. Guo Yaying, whom we called Sister Ying and who had lived next door to our little restaurant, had also opened a restaurant. I am a witness to Sister Ying’s torture. I demand a formal apology and compensation from the Japanese government.

After the death of Zhu Qiaomei’s husband, their restaurant was destroyed and Zhu Qiaomei’s family became destitute, living for decades in an old, tattered shed. On 20 February 2005, Zhu Qiaomei succumbed to illness in her home at the age of ninety-five. The Research Center for Chinese “Comfort Women” sponsored the placement of a gravestone to commemorate her life

.

(Interviewed by Su Zhiliang and Chen Lifei in May 2000, September 2000, February 2001, and March 2001)

Lu Xiuzhen

During their occupation of Chongming Island the Japanese forces set up a comfort station called Hui’an-suo in the Town of Miaozhen. The station, whose buildings no longer exist, was established on the property of local Chinese residents. There was no highway connecting the Town of Miaozhen and the village where Lu Xiuzhen had lived, so the villagers did not expect the Japanese soldiers to traverse the difficult paths to their homes and, therefore, did not hide. Lu Xiuzhen and other women were thus easily kidnapped by Japanese troops and taken to the comfort station

.

10

Figure 11

Lu Xiuzhen, in 2000, giving a talk at the International Symposium on Chinese “Comfort Women” at Shanghai Normal University.

I was born in the Year of the Horse [1917], in a village north of the Miaozhen River on Chongming Island. Both of my parents were poor peasants and had no means of supporting me, so they gave me to the Zhu family to be their adopted daughter. However, my adoptive parents changed their minds later

and wanted to make me their oldest son’s child-bride. I appreciated being their daughter but didn’t want to be their child-daughter-in-law, so I refused and even attempted to run away. Because of this situation, I remained unmarried when I turned twenty-one. [At that time it was a common practice in rural China for females to marry at a very young age, often around or before eighteen. Twenty-one was considered rather old for marriage.] That year [1938] the Japanese army occupied Chongming Island. I heard that the Japanese troops had vacations. Their officers had a week-long vacation, while the soldiers had three days. On their vacation days the military men would come to the villages from where they were stationed. They looted chickens, grain, or anything they could find and shot oxen and pigs to eat. Worse even than that, the Japanese soldiers kidnapped the girls and women they could find. Women in the village were frightened to death, running for their lives as fast as they could when they saw the Japanese soldiers. Those who did not flee fast enough were captured. I was one of the girls captured by Interpreter Jin and the Japanese soldiers. My mother heard about my capture and went to beg the Japanese soldiers to release me. She kneeled in front of them, holding me tightly so that they could not drag me away. The Japanese soldiers then raised their rifles and yelled fiercely at my mother, “Let her go with us or we will burn your house to ashes!” Chinese people suffered hellishly when the Japanese army invaded our country. Japanese soldiers could kill us at will with their guns, so my mother had no way to save me. Those Japanese troops were not human; they were no different from beasts.