Citizen Emperor (64 page)

Authors: Philip Dwyer

It was really after Eylau and the intervention in Spain that the clemency theme was emphasized in a desperate attempt to portray Napoleon in a better light to the people of France. There may have been some parallels with the ancient Roman tradition of depicting leaders in certain poses – Napoleon addressing his men, or entering a conquered city – but these paintings were meant to hide their opposite reality, that of the brutality of war.

76

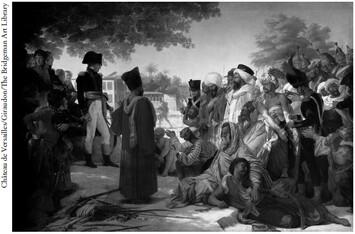

At the Salon of 1808, there were a number of pardon scenes, including Pierre-Narcisse Guérin’s

Bonaparte fait grâce aux révoltés du Caire

(Bonaparte pardoning the rebels in Cairo).

77

Jean-Baptiste Debret,

Napoléon Ier saluant un convoi de blessés autrichiens et rendant hommage au courage malheureux, octobre 1805

(Napoleon salutes a convoy of wounded Austrians, and renders homage to courageous misfortune, October 1805), 1806.

Commissioned in 1806, the painting depicts a scene that took place shortly after the Revolt of Cairo in October 1798 when Bonaparte made a public display of pardoning the rebels on El-Bekir Square. The whole point of paintings like this was to reinforce the paternal nature of the ruler over the ruled. Napoleon is slightly elevated, looking down at the supplicants who look back with a mixture of expressions ranging from fear, humiliation and resignation to what seems to be anger and defiance. It some respects, it is an allegory of the French as both conquerors and liberators. While French guards surround the group of rebels, one of them in the foreground releases a prisoner from his shackles, highlighting not only French moral superiority but also the promise of liberation to those who obey and submit.

Pierre-Narcisse Guerin,

Bonaparte fait grâce aux révoltés du Caire, le 30 octobre 1798

(Bonaparte pardoning the rebels in Cairo, 30 October 1798), 1806–8. Bonaparte offered an amnesty, but only after brutally putting down the revolt. Hundreds were arrested and executed in the days that followed.

78

Ironically, since some of the worst French massacres were committed there, Egypt was also the subject of at least four paintings touching on Napoleon’s clemency. In Guillaume François Colson’s

Trait de clémence du général Bonaparte

(Gesture of clemency from General Bonaparte) of 1812, an Arab mother and her child can be seen adopting a similar position to that of the wounded Lithuanian in Gros’ painting of Eylau, kneeling near Napoleon’s horse, hand outstretched to touch the saddle or the horse: ‘Caesar, you want me to live, well, heal me and I will serve you faithfully as I served Alexander.’

79

Guillaume Francois Colson,

Trait de clémence du général Bonaparte envers une famille arabe lors de l’entrée de l’armée française à Alexandrie le 3 juillet 1798

(Gesture of clemency from General Bonaparte towards an Arab family during the entry of the French army into Alexandria on 3 July 1798), 1812. Napoleon holds out his hand in an act that calls a halt to the killing. Ten years on, he was still getting mileage out of Egypt.

‘A War of Cannibals’

The concerted effort to transform Napoleon’s image was a reaction to a crisis in public opinion, not only among the people, but also in the army, that would persist and grow as military reverses took the shine off Napoleon’s reputation. Spain significantly contributed to that crisis.

After Erfurt, Napoleon prepared to intervene directly in Spain. In fact, with the exception of the invasion of Russia, he paid more attention to preparing public opinion in France about what was happening in Spain than he did about any other campaign.

80

He had decided to intervene personally in August or September, after the military disasters of Bailén (19 July 1808) and Vimeiro (21 August). In the campaign that followed, over three months from November 1808 to January 1809, he was able to redress the situation.

By 6 November 1808, Napoleon was in Vitoria ready to assume command of more than 240,000 men.

81

His plan was quite simple: take Madrid so that Joseph could govern with whatever means were at his disposal. There was little between Bayonne and Madrid that would prevent him from doing so. Under his command was not the army of raw recruits that had been mishandled by the Spanish until now. It was battle hardened and led by some of the best generals the French had, although it has to be said that their performance at certain stages of the campaign was going to be sadly wanting. Be that as it may, Napoleon’s presence in Spain made victory possible, but it also highlighted the deficiencies of a system built around one man. When present, Napoleon demanded and received reports on every aspect of the campaign – civil and military – several times a day. In his absence, with no central command, the French invasion was characterized by inefficiency, exacerbated by the petty rivalries between various military and civilian leaders, none of whom wanted to obey others they considered to be of lesser rank.

‘It is a war of cannibals,’ complained Ney. Atrocities were committed on both sides. As the French moved into territory previously occupied but abandoned, they committed some horrendous depredations – villages were burnt to the ground, ‘rebels’, ‘terrorists’ as the French liked to call them, were hung to set an example, churches were ransacked.

82

In a deeply Catholic country, that was a certain way to alienate the locals. Napoleon expected any rebels caught to be hung and, it is said, all prisoners to be shot, especially if civilians were caught with weapons in hand. The action was designed to strike fear into the population.

83

At least one memoirist asserted that he received the order but was horrified by it.

84

He realized that ‘to have the prisoners shot was a useless barbarity, for it served only to excite the hatred the Spanish felt towards us’.

85

Under Napoleon’s direction, the French inflicted a number of rapid defeats on the Anglo-Spanish armies. General Soult took Burgos on 10 November; the town was pillaged terribly.

86

Even the cemetery was ransacked in the vain hope of finding valuables in the coffins, with decomposing and skeletal bodies being abandoned along the footpath.

87

An officer by the name of Castellane saved a woman from being raped by fifty men, but many others were subjected to the same atrocity.

88

Napoleon entered the city the next day (and Joseph the day after that), disgusted by the stench of rotting bodies from those killed during the fighting. Napoleon stayed in Burgos all of ten days as the bulk of the army marched through, trying to beat his undisciplined army into shape, drawing up notes for Joseph on the government of Spain.

89

General Victor defeated the retreating Anglo-Spanish army at Espinosa de Los Monteros after a battle that lasted twenty hours. Soult took Reinosa, Ney Soria, while Lannes fought and won at Tudela. In every case, the poorly trained Spanish were outnumbered by the French troops. After those encounters, the road to Madrid was wide open. Advance troops approached the northern suburbs of Madrid on 1 December. Napoleon arrived the next day, the anniversary of Austerlitz. He would have preferred to enter the city without a fight, so that Joseph could re-enter the capital on a sound footing. But the

junta

haughtily rejected Napoleon’s offer, delaring that the ‘people of Madrid were resolved to bury themselves under the ruins of their houses rather than permit the French to enter the city’.

90

It was foolish. Napoleon ordered an assault on the capital to begin at dawn on 3 December. It lasted but a few hours and was all over by eleven o’clock that same morning. When Napoleon dispatched another offer to ‘pardon’ the city, the

junta

sent a delegation to negotiate. They were treated to one of Napoleon’s famous scenes of rage; he let loose a storm of abuse and threatened that if the city had not surrendered by six the following morning, he would put to the sword every man taken arms in hand.

91

At the beginning of the nineteenth century, Madrid was about the same size as Berlin with a population around 235,000. Despite the religiosity of the Spanish, the city was an Enlightenment city par excellence, probably better designed and equipped than any the French troops had yet seen. The streets were paved, which was not often the case for Paris, and there were pavements along wide avenues planted with trees.

92

The grand buildings that were the monarchy’s façade hid a large working-class population that had played a significant role in the uprising.

93

Napoleon entered on 4 December. We can discount the official reports according to which he was greeted with ‘an extreme pleasure’.

94

He was to remain there for a little over two weeks, not in the royal palace, which he wanted to leave vacant for his brother, but on the outskirts of the city in a house at Chamartín, working incessantly to put in place the administrative structures that would consolidate his hold on the country and to bring Spain into line with the rest of the Empire: he abolished feudal rights, internal customs barriers and the Inquisition; a third of all Church lands were confiscated;

95

and as was now the norm, the French grabbed whatever they could from the Spanish art collections.

96

The confiscation of Church lands simply confirmed Spaniards in their belief that Napoleon was an atheist. At least some of the pillage was carried out by superior officers for their own personal gain, unable to overcome the temptation of taking ‘two or three small paintings’, hoping that they would go unnoticed.

97

We will pass over the rapine certain generals and marshals became notorious for, but they included Pierre Dupont, Junot, Marmont, Masséna, Lannes and Soult.

98