Citizen Emperor (63 page)

Authors: Philip Dwyer

The opening of the Salon of 1808 displaying Gros’ painting was supposed to coincide with the second anniversary of the battle of Jena.

51

A series of paintings had been ordered to portray the most important scenes from the battlefields of 1806 and 1807, including Napoleon’s entry into Berlin and the dismantling of the monument at Rossbach.

52

Gros’ painting, on the other hand, is one of a number of paintings that portrayed Napoleon as clement ruler, ‘stopping in front of the wounded, having them questioned in their language, having them consoled and helped in front of his eyes’.

53

This was a generous conqueror. Surprised, the vanquished prostrate themselves before him, holding out their arms as a sign of recognition. Napoleon was thus transformed from bloody tyrant into a Christ-like saviour who had come upon the battlefield to bring help to the dying and wounded. In the painting, a wounded enemy soldier, his arm in a sling and on bended knee before Napoleon’s horse, is touching the Emperor’s holy body, but there is also a chasseur ‘who during his dressing forgets his pain, to show his gratitude and devotion to the victor’.

54

Gros is once again conferring on Napoleon the aura of the sacred: the Emperor’s hand is raised, almost as though he is blessing the survivors or the battlefield.

55

The competition was an attempt to quell the rumours that had spread about the extent of the carnage at Eylau. Like the portrait of Bonaparte at Jaffa, Gros’ portrait of Napoleon as ‘healing king’ helping the wounded and dying was meant to counter the accusations that he had uselessly squandered the lives of thousands of men.

56

When it was displayed at the Salon of 1808, it met with enormous success.

57

Unlike Ingres or David, more concerned with the trappings of power in their portraits, Gros attempts to get at Napoleon’s character.

Jaffa

and

Eylau

are in some respects psychological portraits, stressing the complex inner nature of the subject.

58

Nevertheless, as was the case with

Jaffa

, the

Eylau

painting is one of the most graphic portrayals of pain and death yet depicted. In

Jaffa

, however, the suffering was confined to the shadows on the margins of the painting. In

Eylau

, the suffering is centre stage, or at least in the foreground, and therefore quite unmistakable. Gros is meeting head-on the damaging rumours about the carnage. By showing that Napoleon abhorred the suffering, indeed by giving him a Christ-like quality with, seemingly, powers to heal, the artist is declaring that Napoleon could not be held responsible for the suffering.

59

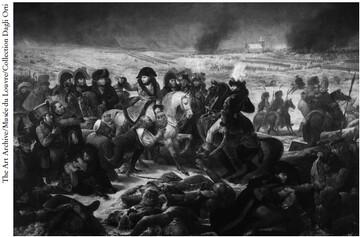

Antoine-Jean Gros,

Napoléon Ier sur le champ de bataille d’Eylau (9 février 1807)

(Napoleon on the battlefield of Eylau (9 February 1807)), 1808. Napoleon’s chief surgeon, Pierre-Francois Percy, is depicted to the left, helping up a Lithuanian who is saluting the Emperor.

Napoleon’s upturned gaze can be interpreted in any number of ways: as a Christ-like supplication to the Almighty; as looking towards his star now hidden by the clouds;

60

as a paradoxical gaze of blindness (‘looking heavenward, Napoleon is “blind” in the sense of looking beyond the field of action’, as if God were absent).

61

Whichever way one looks at it, Napoleon evades responsibility for the carnage. It is the detail that intrigues. Here is a Napoleon, dressed in a pelisse of grey satin lined with fur, a killer of men, but who is portrayed as a saint. What can it possibly mean to offer a blessing to the victims of the battle?

62

Napoleon is meant to console, to help the wounded. His face now takes on the expression of ‘heroic humanity’.

63

He thus appears to be even more heroic.

64

The contrast between the snow and Napoleon’s entourage, who are painted in darker colours than the Emperor, and the pallor of his face are all used to create the perception that we are looking at a sublime character. Moreover, despite the fact that Napoleon was driven by military conquest – indeed his whole being existed to conquer – he knew that he could not simply rely on brutal military glory to maintain or justify his power. He needed respect, and for that he had to be seen to engage in acts that were worthy of emulation.

The Clemency of His Majesty

The theme of Napoleon as a clement ruler was something he had been at pains to emphasize since first coming to power. Propaganda after Marengo, for example, focused on Bonaparte as a humane leader, beloved by his troops, a typology that dates back to the first Italian campaign. Paintings from the earliest years of his reign began to portray Bonaparte not only as the victorious general, but also as a general who cared for his men. The Salon of 1801 displayed two such examples by Nicolas-Antoine Taunay,

Passage des Alpes par le général Bonaparte

(The crossing of the Alps by General Bonaparte), in which Bonaparte is encouraging a tired soldier to lift a cannon wheel, and the

Attaque du

Fort

de

Bard

(Attack on Fort Bard), in which soldiers contemplate a sleeping Bonaparte ‘with the most tender sensitivity’.

65

In this respect, the image of a caring and even Christian (because pardoning) Bonaparte was in stark contrast to the systematic elimination of all opposition in France, which as we have seen sometimes resulted in executions, just as it was in contrast to the conditions in which the troops actually lived and died on the battlefields and in the hospitals. The newspapers made sure to mention any act that reinforced Bonaparte’s compassionate character. In the days leading up to the coronation, for example, he pardoned a ‘large number’ of prisoners, because they were fathers often locked away for debt.

66

In 1804, before the proclamation of the Empire, it was incumbent upon the soon-to-be-crowned ‘father of the people’ to help fathers of families. After the foundation of the Empire, stories about Napoleon’s clemency continued to circulate – one comes across them in the newspapers, pamphlets, memoirs and letters of the day

67

– but they were also present in artistic representations of Napoleon, as well as in literature, the theatre and opera.

68

The idea is especially prevalent in the later paintings of the Empire, and coincides in part with the resurrection of monarchical notions of divine right – we can thus see Napoleon granting clemency to his defeated enemies but also extending French civilization to barbarian cultures – and in part with the rising toll of dead and wounded across Europe.

69

In order to counter the anti-Napoleonic propaganda that depicted him as warmonger and butcher, government-inspired art increasingly focused on the idea of Napoleon as merciful ruler.

An example is the case of the Prussian Prince Hatzfeld, arrested in Berlin in 1806 on suspicion of spying. Sent to present Napoleon with the keys of the city, as the troops were filing past he counted them and sent off his findings to Prince Hohenlohe, in command of what was left of the Prussian army. The evidence against him was circumstantial, so it is quite possible that after the pleas of his wife, who was eight months pregnant and who supposedly fainted a number of times in the course of a reading of the indictment, Napoleon, ‘touched’ by this show of feelings,

70

used this occasion as an overt demonstration of his clemency. If any artists were looking for a subject to paint, this was one that was ready-made. A number approached Vivant Denon with proposals for works on the subject.

71

Paintings and engravings of Mme de Hatzfeld kneeling, crying, supplicating Napoleon abounded after 1806.

72

That Napoleon was according an act of mercy to a woman was not without significance. It was possibly seen as more acceptable to accord clemency to a woman, since she is in a position of submission, than to a male conspirator, for example. Napoleon was not, however, averse to forcing the king’s Noble Guard, the very same who had sharpened their blades on the steps of the French embassy at the outbreak of war, to march past the embassy as prisoners between two rows of soldiers, a gesture that might be considered a little spiteful but was approved of by some Berliners who blamed the Guard for pushing the king into war.

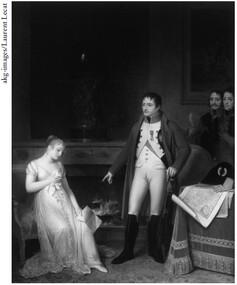

Marguerite Gerard,

La clémence de Napoléon Ier: Napoléon et la princesse de Hatzfeld

(The clemency of Napoleon I: Napoleon and the Princess of Hatzfeld), 1806. In this painting, later bought by Josephine, Napoleon points to the fire, indicating where Mme Hatzfeld should throw the letter of accusation against her husband. It was the final act, so to speak, in the melodrama. The gesture in the painting is, in any event, one of

clementia

– clemency.

73

In 1806, Jean-François Dunant painted the

Trait de générosité française

(Gesture of French generosity), in which Napoleon is seen distributing money to Austrian prisoners (very similar, it has to be said, to Philibert-Louis Debucourt’s 1785 painting

Le trait d’humanité de Louis XVI

, in which he is portrayed distributing alms to a family of poor peasants). The year 1806 also saw Jean-Baptiste Debret’s

Napoléon Ier saluant un convoi de blessés autrichiens

(Napoleon salutes a convoy of wounded Austrians). Debret was inspired by a piece of official propaganda, a bulletin that was reprinted in the

Journal de Paris

shortly after the battle of Ulm. It described Napoleon’s benevolence, based on an eyewitness account, when, seeing a line of Austrian wounded file past him, he took off his hat, made all the other officers in his entourage do the same and said aloud, ‘Honour to courageous misfortune’ (

Honneur au courage malheureux

).

74

Since there are no other accounts of this particular anecdote, it may be entirely fictive. The point being made, however, was that Napoleon was not only a victorious general, but also a benevolent, generous and kind ruler. This type of painting had the added advantage of taking away the focus from scenes of battle and the French casualties that ensued.

75

Napoleon’s compassion for others goes so far as to encompass the enemy.