Color: A Natural History of the Palette (14 page)

Read Color: A Natural History of the Palette Online

Authors: Victoria Finlay

Tags: #History, #General, #Art, #Color Theory, #Crafts & Hobbies, #Nonfiction

Nobody knows when ink was first discovered, but scholars tend to agree that it was already well established in both China and Egypt (as well as plenty of places in between) by about four thousand years ago. The Biblical Joseph—he of the multicolored coat—was viceroy of Egypt in around 1700 BC. He was able to manage all those famines and other agricultural crises only with the help of a huge city of scribes to record everything and send letters—written in the cursive or “hieratic” version of hieroglyphics— which would be posted by teams of runners. Each Egyptian clerk had two kinds of ink—red and black—which they used to carry around in pots set into portable desks. The black was made of soot, mixed with gum to make it stick to the papyrus.

Chinese ink—also known, confusingly, as Indian ink—is also made mainly of soot, and the best of it is made when a pine log, or oil, or lacquer resin, or even the lees of wine, have been burned. One vivid description from ancient China

12

is of hundreds of small earthenware oil lamps enclosed in a bamboo screen to keep out the breeze. Every half an hour or so, workers would remove the soot from the lamp funnels, using feathers. When I first read about the feathers I thought the manufacturing process sounded delightfully flouncy, but actually it must have been a nasty smoky job, which would have left treacherous carbon deposits on the lungs of every employee.

When this ink meets dampened blotting paper it doesn’t leak into the kind of multicolored spider’s webs we see with modern fountain-pen inks

13

—in fact the ink must not leak at all, since Chinese paintings are stretched onto scrolls by wetting them. And yet, conceptually, for Chinese artists a thousand years ago, black ink did contain all the colors, just as in Zen philosophy a grain of rice contains the whole world. The Daoist classic text, the

Dao De Jing

(

Tao Te Ching

), warns that dividing the world into the five colors (black, white, yellow, red and blue) would “blind the eye” to true perception. The message is that we would all think so much more clearly if we didn’t divide the world at all.

The Daoists were reacting to a strict Confucian world, of course, where everything was separated into neat categories. The Confucians would define a cup by what it looked like, the Daoists by the nothing in the middle, because without that it wouldn’t be a cup. So in terms of colors, the greatest of artists should be able to make a peacock seem iridescent, or a peach seem pink, without using any colored pigments at all, and in that way they would get closer to understanding its true nature. By the time of the Tang dynasty this is exactly what the amateur artists were trying to do. Colors were for professional painters—who were rather sneered upon by the elite, as creating something necessary but vulgar. Black, on the other hand, was for the gentleman artists, who combined the skills of poetry and painting, and who wanted to portray the landscape of the mind, not of the eye. Unfortunately none of the Tang monochrome paintings has survived—but during the Southern Song dynasty in the thirteenth century this became quite a mainstream artistic theory, and there are plenty of examples from this period. One of the most precious paintings in the National Palace Museum collection in Taipei is a monochrome scroll painting by the thirteenth-century landscape painter Xia Gui.

14

It is called Remote

View of Streams and Hills

, and I love it because like so many so-called “scholar’s paintings” it is much more than a landscape: it is a mental journey. You can’t try to pretend you are really looking at hills and streams from some kind of remote vantage point. Because as your eyes move along the eight-meter-long scroll the viewpoint keeps changing and sometimes you are above the landforms and sometimes below them, as if you are soaring on the wings of a crane or an

apsara

—a Chinese angel. It doesn’t matter what the colors are: angels (or probably cranes) do not divide the world into colors anyway.

This monochrome philosophy can be summed up in an anecdote about Su Dongpo, an infamous scholar-artist living in the eleventh century. He created marvellous paintings and poems, but he also left a mythology of endearing misadventures. Tales of Su Dongpo sometimes read like wise fables of a naughty innocent. Once, for example, Su was criticized for painting a picture of a leafy bamboo using red ink. Not realistic, his critics said gleefully. “Then what color should I have used?” he asked. “Black, of course,” came the answer.

Another time Su Dongpo (who apparently ate three hundred lychees a day, and once announced that he liked living next to a cattle farm as it meant he would never get lost because he could always follow the cow pats home) was experimenting with making ink. According to legend, he was so enthusiastic in his endeavor (and in his wine-drinking) that he almost burned down his house. “Soot from poets’ burned homes” was not something he wanted added to the litany of ink recipe ingredients, although it has something of the whimsical about it, and I am sure he would have been wryly amused by the idea.

From early times both the Persians and the Chinese thought it was desirable to have ink that not only travelled seductively across the paper, but which also smelled wonderful. So they would add perfumes, to make writing the sensual experience that scholars deserved. Sometimes recipes for ink read like the random elements of a love poem: cloves, honey, locusts, the virgin pressing of olives, powdered pearl, scented musk, rhinoceros horn, jade, jasper, as well as, of course—most poignant and most common—that exquisite smoke of pine trees in autumn. Of all the luxury ingredients they probably needed the musk most: sometimes the binding glue was from rhino horn or yak skin, but sometimes it was from fish intestines, as it sometimes still is, and in its raw state it must have been horribly smelly.

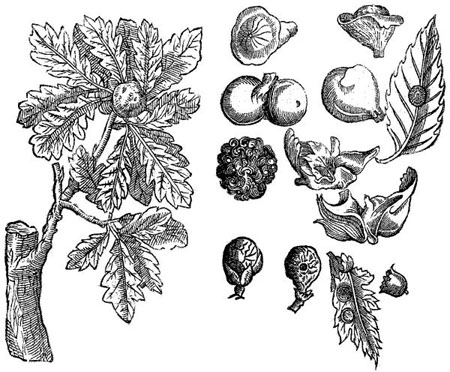

The oak and the oak galls (1640)

Another kind of medieval ink was made in the spring, by a wasp. The female

Cynips quercus folii

is notable for her unusual nest-making—puncturing a home for her eggs in the soft young buds of the oak tree. The tree quite naturally protests at the invasion and forms little nutlike growths around the wasp holes, and it is these protective oak galls which (when collected before the wasp eggs hatch) form the basis of an intense black. It was used throughout Europe from at least medieval times, and the process was probably learned from the Arabs, who used it for ink, clothes dyeing and some mascara. It contains tannin—a highly astringent, acidic substance found in many plants, although rarely in such concentrated form as in nut galls—and the recipe can also be replicated with tea leaves. The Prado Museum in Madrid owns two small ink sketches by Goya which demonstrate the difference between iron and soot inks.

And a Pity You Aren’t Interested in Something Else

shows a woman holding a water jar, stopping to flirt with somebody just out of the frame.

The Egg Vendor

shows a courageous young woman striding across the country with her egg basket, stopping for nothing, not even bandits, certainly not flirtation. This one was made with Indian ink and it has a much finer definition—almost like charcoal, with a dryness to it. The first was sketched with iron gall ink: it is much softer, as if it had been soaked in the contents of the girl’s water jar.

In

The Art Forger’s Handbook

, Eric Hebborn bemoaned the difficulty of finding iron gall ink in artist-supply shops in the 1980s and 1990s and described how to recreate this ink’s curious tints which range from faded yellow to strong black (via rusty browns and greens)—he followed an ancient recipe requiring either water or wine. He would mix the liquid with gum arabic, galls and coconut kernels, and leave the stew covered under warm sunlight for several days. If you cannot find galls, then rotten acorns were almost as good, Hebborn added.

15

And as for the wine, he preferred to drink it rather than add it to the broth.

PERMANENCE

The Corinthian artist would have been amazed to think that her struggle for permanence—to capture a fleeting image or idea forever—would be mirrored throughout the millennia, although with varying results. Even as recently as the early twentieth century a Professor Traill in the United States became obsessed by finding a perfectly permanent ink. According to ink specialist David Carvalho, Traill was convinced he had found something that would last for aeons. He observed how it resisted the action of all acids and alkalis he tried it with, and so he sent it off to banks and schools for testing. Most thought it was excellent, “but, alas, an experimenting scribbler, thoughtlessly or otherwise, applied a simple test undreamt of by the Professor, and with a wet sponge completely washed off his ‘indelible,’ and thereby finished his career as an amateur ink-maker!”

16

Today’s black inks tend to be made of aniline blues, reds, yellows and purples, blending together so they absorb most of the light rays that shine on them, and give the impression of being black. There is, however, one notable exception to this standard recipe, which I came across during my brother’s wedding. My mother was one of two witnesses, and when it came to the appropriate moment she took her fountain pen out of her handbag and prepared to sign. “No,” cried the registrar in alarm, stopping her hand. “You have to use this pen.” She explained later that it contained special ink for legal documents: it is designed to last for many generations, and has the unusual quality of growing darker with age. It comes from the Central Registry Office and it arrives in an inkpot, not in cartridges. “Actually we hate it: it’s too thick to use in a normal fountain pen, and if we get it on our clothes it burns into them and we can’t remove it.”

The Liverpool-based ink manufacturer Dormy Ltd. supplies the Central Registry Office of England and Wales with around half a ton of registrar’s ink every year: births, deaths and marriages involve a lot of writing. Peter Thelfall, who is a chemist at Dormy, explained why it is different from any other ink. Most fountain-pen inks today, he said, are made up of colored dyes and water, and if you leave something written with them on a sunny window ledge then the words will quickly fade. There are dyes in registrar’s ink too, and they will fade. But that doesn’t matter, because the ink also contains a cocktail of chemicals that react with the surface of the paper and oxidize, turning to a black that will not fade in sunlight and is resistant to water. “You could sign with purple registrar’s ink, or red—it doesn’t matter what the undertone dye is, it will still go black on the paper,” he explained. The substances in registrar’s ink that make it burn into the paper are tannic and gallic acid (today Dormy uses a synthetic version of natural oak galls), mixed with iron sulphate, a chemical that is better known as vitriol. It is curious that every legal wedding in England and Wales should be recorded with such a high content of a substance that symbolically suggests acidity and dissent.

17

Today when you order a three-hundred-year-old book from the British Library you can be fairly certain that the ink will still be dark enough to be legible. This was not, however, apparent to the first publisher of printed books, and when Johannes Gutenberg invented the moving-type printing press in Germany in the 1450s, he realized he had a serious problem: his first trials showed up as faded and brown, even when he used the best ink available. There was no point in being able to mass-produce books if you couldn’t read them and Gutenberg recognized that he had to invent a decent printing ink if he was going to change the world. He was lucky. A few years before, the Flemish artist Jan van Eyck had helped revitalize the use of oils rather than egg in paints. And the new printers found they could use that same technology to create oily inks—it was just a matter of playing around with combinations of turpentine, linseed oil, walnut oil, pitch, lampblack and resin until they got it right. The final recipe used on the forty-two-line Gutenberg Bible is lost to posterity, but we do know that its admirers were impressed by the blackness of the print.

Linseed oil was a near-perfect binding medium, but it needed to be treated before it could be used.

The Printing Ink Manual

, published in 1961, gives a wonderful image of a seventeenth-century printer and his employees taking a day off to replenish their ink supplies. They would go beyond the city walls to an open space, and there they would set up great pots for heating the oil. When it was boiling, the mucilage separated off, and the apprentices would sop it up by throwing bread into the vats: it must have smelled like a huge greasy fry-up. The whole process took hours, so the master would traditionally give the men flasks of schnapps, which they would soak up with the fried bread. Lampblack and the other ingredients would be added the next day, when “both oil and heads had cooled.”

DARK DYES

In Western culture black often represents death. Blackness is, after all, a description of what happens when all light is absorbed and when nothing is reflected back, so if you believe that there is no return from death then black is a marvellous symbol. It is also, in the West, a sign of seriousness, so for example when the sixteenth-century Venetians were thought to be too frivolous a law was passed to the effect that all gondolas should be painted black, to signify the end of the party. As such, black was adopted enthusiastically—if any group so historically subdued could do anything enthusiastically—by the Puritans who emerged in Europe in the seventeenth century.