Complete Works of Wilkie Collins (176 page)

Read Complete Works of Wilkie Collins Online

Authors: Wilkie Collins

He looked up at her so quickly, with such a fierce, steady, serpent-glitter in his light-grey eyes, that she recoiled a step or two; still pleading, however, with desperate perseverance for an answer to her last question.

“Only tell me, sir, that you don’t mean to take little Mary away, and I won’t ask you to say so much as another word! You’ll leave her with Mr. and Mrs. Blyth, won’t you, sir? For your sister’s sake, you’ll leave her with the poor bed-ridden lady that’s been like a mother to her for so many years past? — for your dear, lost sister’s sake, that I was with when she died — ”

“Tell me about her.” He said those few words with surprising gentleness, as Mrs. Peckover thought, for such a rough-looking man.

“Yes, yes, all you want to know,” she answered. “But I can’t stop here. There’s my brother — I’ve got such a turn with seeing you, it’s almost put him out of my head — there’s my brother, that I must go back to, and see if he’s asleep still. You just please to come along with me, and wait in the parlor — it’s close by — while I step upstairs — ” (Here she stopped in great confusion. It seemed like running some desperate risk to, ask this strange, stern-featured relation of Mary Grice’s into her brother’s house.) “And yet,” thought Mrs. Peckover, “if I can only soften his heart by telling him about his poor unfortunate sister, it may make him all the readier to leave little Mary — ”

At this point her perplexities were cut short by Matthew himself, who said, shortly, that he had been to Dawson’s Buildings already to look after her. On hearing this, she hesitated no longer. It was too late to question the propriety or impropriety of admitting him now.

“Come away, then,” she said; “don’t let’s wait no longer. And don’t fret about the infamous state they’ve left things in here,” she added, thinking to propitiate him, as she saw his eyes turn once more at parting, on the broken board and the brambles around the grave. “I know where to go, and who to speak to — ”

“Go nowhere, and speak to nobody,” he broke in sternly, to her great astonishment. “All what’s got to be done to it, I mean to do myself.”

“You!”

“Yes, me. It was little enough I ever did for her while she was alive; and it’s little enough now, only to make things look decent about the place where she’s buried. But I mean to do that much for her; and no other man shall stir a finger to help me.”

Roughly as it was spoken, this speech made Mrs. Peckover feel easier about Madonna’s prospects. The hard-featured man was, after all, not so hard-hearted as she had thought him at first. She even ventured to begin questioning him again, as they walked together towards Dawson’s Buildings.

He varied very much in his manner of receiving her inquiries, replying to some promptly enough, and gruffly refusing, in the plainest terms, to give a word of answer to others.

He was quite willing, for example, to admit that he had procured her temporary address at Bangbury from her daughter at Rubbleford; but he flatly declined to inform her how he had first found out that she lived at Rubbleford at all. Again, he readily admitted that neither Madonna nor Mr. Blyth knew who he really was; but he refused to say why he had not disclosed himself to them, or when he intended — if he ever intended at all — to inform them that he was the brother of Mary Grice. As to getting him to confess in what manner he had become possessed of the Hair Bracelet, Mrs. Peckover’s first question about it, although only answered by a look, was received in such a manner as to show her that any further efforts on her part in that direction would be perfectly fruitless.

On one side of the door, at Dawson’s Buildings, was Mr. Randle’s shop; and on the other was Mr. Randle’s little dining parlor. In this room Mrs. Peckover left Mat, while she went up stairs to see if her sick brother wanted anything. Finding that he was still quietly sleeping, she only waited to arrange the bed-clothes comfortably about him, and to put a hand-bell easily within his reach in case he should awake, and then went down stairs again immediately.

She found Mat sitting with his elbows on the one little table in the dining-parlor, his head resting on his hands. Upon the table lying by the side of the Bracelet, was the lock of hair out of Jane Holdsworth’s letter, which he had yet once more taken from his pocket to look at. “Why, mercy on me!” cried Mrs. Peckover, glancing at it, “surely it’s the same hair that’s worked into the Bracelet! Wherever, for goodness sake, did you get that?”

“Never mind where I got it. Do you know whose hair it is? Look a little closer. The man this hair belonged to was the man she trusted in — and he laid her in the churchyard for her pains.”

“Oh! who was he? who was he?” asked Mrs. Peckover, eagerly

“Who was he?” repeated Matthew, sternly. “What do you mean by asking me that?”

“I only mean that I never heard a word about the villain — I don’t so much as know his name.”

“You don’t?” He fastened his eyes suspiciously on her as he said those two words.

“No; as true as I stand here I don’t. Why, I didn’t even know that your poor dear sister’s name was Grice till you told me.”

His look of suspicion began to change to a look of amazement as he heard this. He hurriedly gathered up the Bracelet and the lock of hair, and put them into his pocket again.

“Let’s hear first how you met with her,” he said. “I’ll have a word or two about the other matter afterwards.”

Mrs. Peckover sat down near him, and began to relate the mournful story which she had told to Valentine, and Doctor and Mrs. Joyce, now many years ago, in the Rectory dining-room. But on this occasion she was not allowed to go through her narrative uninterruptedly. While she was speaking the few simple words which told how she had sat down by the road-side, and suckled the half-starved infant of the forsaken and dying Mary Grice, Mat suddenly reached out his heavy, trembling hand, and took fast hold of hers. He griped it with such force that, stout-hearted and hardy as she was, she cried out in alarm and pain, “Oh, don’t! you hurt me — you hurt me!”

He dropped her hand directly, and turned his face away from her; his breath quickening painfully, his fingers fastening on the side of his chair, as if some great pang of oppression were trying him to the quick. She rose and asked anxiously what ailed him; but, even as the words passed her lips, he mastered himself with that iron resolution of his which few trials could bend, and none break, and motioned to her to sit down again.

“Don’t mind me,” he said; “I’m old and tough-hearted with being battered about in the world, and I can’t give myself vent nohow with talking or crying like the rest of you. Never mind; it’s all over now. Go on.”

She complied, a little nervously at first; but he did not interrupt her again. He listened while she proceeded, looking straight at her; not speaking or moving — except when he winced once or twice, as a man winces under unexpected pain, while Mary’s death-bed words were repeated to him. Having reached this stage of her narrative, Mrs. Peckover added little more; only saying, in conclusion: “I took care of the poor soul’s child, as I said I would; and did my best to behave like a mother to her, till she got to be ten year old; then I give her up — because it was for her own good — to Mr. Blyth.”

He did not seem to notice the close of the narrative. The image of the forsaken girl, sitting alone by the roadside, with her child’s natural sustenance dried up within her — travel-worn, friendless, and desperate — was still uppermost in his mind; and when he next spoke, gratitude for the help that had been given to Mary in her last sore distress was the one predominant emotion, which strove roughly to express itself to Mrs. Peck over in these words:

“Is there any living soul you care about that a trifle of money would do a little good to?” he asked, with such abrupt eagerness that she was quite startled by it.

“Lord bless me!” she exclaimed, “what do you mean? What has that got to do with your poor sister, or Mr. Blyth?”

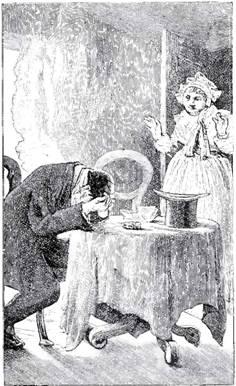

“It’s got this to do,” burst out Matthew, starting to his feet, as the struggling gratitude within him stirred body and soul both together; “you turned to and helped Mary when she hadn’t nobody else in the world to stand by her. She was always father’s darling — but father couldn’t help her then; and I was away on the wrong side of the sea, and couldn’t be no good to her neither. But I’m on the right side, now; and if there’s any friends of yours, north, south, east, or west, as would be happier for a trifle of money, here’s all mine; catch it, and give it ‘em.” (He tossed his beaver-skin roll, with the bank-notes in it, into Mrs. Peckover’s lap.) “Here’s my two hands, that I dursn’t take a holt of yours with, for fear of hurting you again; here’s my two hands that can work along with any man’s. Only give ‘em something to do for you, that’s all! Give ‘em something to make or mend, I don’t care what — ”

“Hush! hush!” interposed Mrs. Peckover; “don’t be so dreadful noisy, there’s a good man! or you’ll wake my brother up stairs. And, besides, where’s the use to make such a stir about what I done for your sister? Anybody else would have took as kindly to her as I did, seeing what distress she was in, poor soul! Here,” she continued, handing him back the beaver-skin roll; “here’s your money, and thank you for the offer of it. Put it up safe in your pocket again. We manage to keep our heads above water, thank God! and don’t want to do no better than that. Put it up in your pocket again, and then I’ll make bold to ask you for something else.”

“For what?” inquired Mat, looking her eagerly in the face.

“Just for this: that you’ll promise not to take little Mary from Mr. Blyth. Do, pray do promise me you won’t.”

“I never thought to take her away,” he answered. “Where should I take her to? What can a lonesome old vagabond, like me, do for her? If she’s happy where she is — let her stop where she is.”

“Lord bless you for saying that!” fervently exclaimed Mrs. Peckover, smiling for the first time, and smoothing out her gown over her knees with an air of inexpressible relief. “I’m rid of my grand fright now, and getting to breathe again freely, which I haven’t once yet been able to do since I first set eyes on you. Ah! you’re rough to look at; but you’ve got your feelings like the rest of us. Talk away now as much as you like. Ask me about anything you please — ”

“What’s the good?” he broke in, gloomily. “You don’t know what I wanted you to know. I come down here for to find out the man as once owned this,” — he pulled the lock of hair out of his pocket again — ”and you can’t help me. I didn’t believe it when you first said so, but I do now.”

“Well, thank you for saying that much; though you might have put it civiler — ”

“His name was Arthur Carr. Did you never hear tell of anybody with the name of Arthur Carr?”

“No: never — never till this very moment.”

“The Painter-man will know,” continued Mat, talking more to himself than to Mrs. Peckover. “I must go back, and chance it with the Painter-man, after all.”

“Painter-man?” repeated Mrs. Peckover. “Painter? Surely you don’t mean Mr. Blyth?”

“Yes, I do.”

“Why, what in the name of fortune can you be thinking of! How should Mr. Blyth know more than me? He never set eyes on little Mary till she was ten year old; and he knows nothing about her poor unfortunate mother except what I told him.”

These words seemed at first to stupefy Mat: they burst upon him in the shape of a revelation for which he was totally unprepared. It had never once occurred to him to doubt that Valentine was secretly informed of all that he most wished to know. He had looked forward to what the painter might be persuaded — or, in the last resort, forced — to tell him, as the one certainty on which he might finally depend; and here was this fancied security exposed, in a moment, as the wildest delusion that ever man trusted in! What resource was left? To return to Dibbledean, and, by the legal help of Mr. Tatt, to possess himself of any fragments of evidence which Joanna Grice might have left behind her in writing? This seemed but a broken reed to depend on; and yet nothing else now remained.