Complete Works of Wilkie Collins (210 page)

Read Complete Works of Wilkie Collins Online

Authors: Wilkie Collins

Uncle Joseph shook his head at these last words, and touched the stop of the musical box. “Mozart shall wait a little,” he said, gravely, “till I have told you something. Sarah, hear what I say, and drink your tea, and own to me whether I speak the truth or not. What did I, Joseph Buschmann, tell you, when you first came to me in trouble, fourteen, fifteen, ah more! sixteen years ago, in this town, and in this same house? I said then, what I say again now: ‘Sarah’s sorrow is my sorrow, and Sarah’s joy is my joy;’ and if any man asks me reasons for that, I have three to give him.”

He stopped to stir up his niece’s tea for the second time, and to draw her attention to it by tapping with the spoon on the edge of the cup.

“Three reasons,” he resumed. “First, you are my sister’s child — some of her flesh and blood, and some of mine, therefore, also. Second, my sister, my brother, and lastly me myself; we owe to your good English father — all. A little word that means much, and may be said again and again — all. Your father’s friends cry, Fie! Agatha Buschmann is poor! Agatha Buschmann is foreign! But your father loves the poor German girl, and he marries her in spite of their Fie, Fie. Your father’s friends cry Fie! again; Agatha Buschmann has a musician brother, who gabbles to us about Mozart, and who cannot make to his porridge salt. Your father says, Good! I like his gabble; I like his playing; I shall get him people to teach; and while I have pinches of salt in my kitchen, he to his porridge shall have pinches of salt too. Your father’s friends cry Fie! for the third time. Agatha Buschmann has another brother, a little Stupid-Head, who to the others gabble can only listen and say Amen. Send him trotting; for the love of Heaven, shut up all the doors and send Stupid-Head trotting, at least. Your father says, No! Stupid-Head has his wits in his hands; he can cut and carve and polish; help him a little at the starting, and after he shall help himself. They are all gone now but me! Your father, your mother, and Uncle Max — they are all gone. Stupid-Head alone remains to remember and to be grateful — to take Sarah’s sorrow for his sorrow, and Sarah’s joy for his joy.”

He stopped again to blow a speck of dust off the musical box. His niece endeavored to speak, but he held up his hand, and shook his forefinger at her warningly.

“No,” he said. “It is yet my business to talk, and your business to drink tea. Have I not my third reason still? Ah! you look away from me; you know my third reason before I say a word. When I, in my turn, marry, and my wife dies, and leaves me alone with little Joseph, and when the boy falls sick, who comes then, so quiet, so pretty, so neat, with the bright young eyes, and the hands so tender and light? Who helps me with little Joseph by night and by day? Who makes a pillow for him on her arm when his head is weary? Who holds this box patiently at his ear? — yes! this box, that the hand of Mozart has touched — who holds it closer, closer always, when little Joseph’s sense grows dull, and he moans for the friendly music that he has known from a baby, the friendly music that he can now so hardly, hardly hear? Who kneels down by Uncle Joseph when his heart is breaking, and says, ‘Oh, hush! hush! The boy is gone where the better music plays, where the sickness shall never waste or the sorrow touch him more?’ Who? Ah, Sarah! you cannot forget those days; you cannot forget the Long Ago! When the trouble is bitter, and the burden is heavy, it is cruelty to Uncle Joseph to keep away; it is kindness to him to come here.”

The recollections that the old man had called up found their way tenderly to Sarah’s heart. She could not answer him; she could only hold out her hand. Uncle Joseph bent down, with a quaint, affectionate gallantry, and kissed it; then stepped back again to his place by the musical box. “Come!” he said, patting it cheerfully, “we will say no more for a while. Mozart’s box, Max’s box, little Joseph’s box, you shall talk to us again!”

Having put the tiny machinery in motion, he sat down by the table, and remained silent until the air had been played over twice. Then observing that his niece seemed calmer, he spoke to her once more.

“You are in trouble, Sarah,” he said, quietly. “You tell me that, and I see it is true in your face. Are you grieving for your husband?”

“I grieve that I ever met him,” she answered. “I grieve that I ever married him. Now that he is dead, I cannot grieve — I can only forgive him.”

“Forgive him? How you look, Sarah, when you say that! Tell me — ”

“Uncle Joseph! I have told you that my husband is dead, and that I have forgiven him.”

“You have forgiven him? He was hard and cruel with you, then? I see; I see. That is the end, Sarah — but the beginning? Is the beginning that you loved him?”

Her pale cheeks flushed; and she turned her head aside. “It is hard and humbling to confess it,” she murmured, without raising her eyes; “but you force the truth from me, uncle. I had no love to give to my husband — no love to give to any man.”

“And yet you married him! Wait! it is not for me to blame. It is for me to find out, not the bad, but the good. Yes, yes; I shall say to myself; she married him when she was poor and helpless; she married him when she should have come to Uncle Joseph instead. I shall say that to myself; and I shall pity, but I shall ask no more.”

Sarah half reached her hand out to the old man again — then suddenly pushed her chair back, and changed the position in which she was sitting. “It is true that I was poor,” she said, looking about her in confusion, and speaking with difficulty. “But you are so kind and so good, I cannot accept the excuse that your forbearance makes for me. I did not marry him because I was poor, but — ” She stopped, clasped her hands together, and pushed her chair back still farther from the table.

“So! so!” said the old man, noticing her confusion. “We will talk about it no more.”

“I had no excuse of love; I had no excuse of poverty,” she said, with a sudden burst of bitterness and despair. “Uncle Joseph, I married him because I was too weak to persist in saying No! The curse of weakness and fear has followed me all the days of my life! I said No to him once. I said No to him twice. Oh, uncle, if I could only have said it for the third time! But he followed me, he frightened me, he took away from me all the little will of my own that I had. He made me speak as he wished me to speak, and go where he wished me to go. No, no, no — don’t come to me, uncle; don’t say anything. He is gone; he is dead — I have got my release; I have given my pardon! Oh, if I could only go away and hide somewhere! All people’s eyes seem to look through me; all people’s words seem to threaten me. My heart has been weary ever since I was a young woman; and all these long, long years it has never got any rest. Hush! the man in the shop — I forgot the man in the shop. He will hear us; let us talk in a whisper. What made me break out so? I’m always wrong. Oh me! I’m wrong when I speak; I’m wrong when I say nothing; wherever I go and whatever I do, I’m not like other people. I seem never to have grown up in my mind since I was a little child. Hark! the man in the shop is moving — has he heard me? Oh, Uncle Joseph! do you think he has heard me?”

Looking hardly less startled than his niece, Uncle Joseph assured her that the door was solid, that the man’s place in the shop was at some distance from it, and that it was impossible, even if he heard voices in the parlor, that he could also distinguish any words that were spoken in it.

“You are sure of that?” she whispered, hurriedly. “Yes, yes, you are sure of that, or you would not have told me so, would you? We may go on talking now. Not about my married life: that is buried and past. Say that I had some years of sorrow and suffering, which I deserved — say that I had other years of quiet, when I was living in service with masters and mistresses who were often kind to me when my fellow-servants were not — say just that much about my life, and it is saying enough. The trouble that I am in now, the trouble that brings me to you, goes back further than the years we have been talking about — goes back, back, back, Uncle Joseph, to the distant day when we last met.”

“Goes back all through the sixteen years!” exclaimed the old man, incredulously. “Goes back, Sarah, even to the Long Ago!”

“Even to that time. Uncle, you remember where I was living, and what had happened to me, when — ”

“When you came here in secret? When you asked me to hide you? That was the same week, Sarah, when your mistress died; your mistress who lived away west in the old house. You were frightened, then — pale and frightened as I see you now.”

“As every one sees me! People are always staring at me; always thinking that I am nervous, always pitying me for being ill.”

Saying these words with a sudden fretfulness, she lifted the tea-cup by her side to her lips, drained it of its contents at a draught, and pushed it across the table to be filled again. “I have come all over thirsty and hot,” she whispered. “More tea, Uncle Joseph — more tea.”

“It is cold,” said the old man. “Wait till I ask for hot water.”

“No!” she exclaimed, stopping him as he was about to rise. “Give it me cold; I like it cold. Let nobody else come in — I can’t speak if anybody else comes in.” She drew her chair close to her uncle’s, and went on: “You have not forgotten how frightened I was in that by-gone time — do you remember why I was frightened?”

“You were afraid of being followed — that was it, Sarah. I grow old, but my memory keeps young. You were afraid of your master, afraid of his sending servants after you. You had run away; you had spoken no word to anybody; and you spoke little — ah, very, very little — even to Uncle Joseph — even to me.”

“I told you,” said Sarah, dropping her voice to so faint a whisper that the old man could barely hear her — ”I told you that my mistress had left me a Secret on her death-bed — a Secret in a letter, which I was to give to my master. I told you I had hidden the letter, because I could not bring myself to deliver it, because I would rather die a thousand times over than be questioned about what I knew of it. I told you so much, I know. Did I tell you no more? Did I not say that my mistress made me take an oath on the Bible? — Uncle! are there candles in the room? Are there candles we can light without disturbing anybody, without calling anybody in here?”

“There are candles and a match-box in my cupboard,” answered Uncle Joseph. “But look out of window, Sarah. It is only twilight — it is not dark yet.”

“Not outside; but it is dark here.”

“Where?”

“In that corner. Let us have candles. I don’t like the darkness when it gathers in corners and creeps along walls.”

Uncle Joseph looked all round the room inquiringly; and smiled to himself as he took two candles from the cupboard and lighted them. “You are like the children,” he said playfully, while he pulled down the window-blind. “You are afraid of the dark.”

Sarah did not appear to hear him. Her eyes were fixed on the corner of the room which she had pointed out the moment before. When he resumed his place by her side, she never looked round, but laid her hand on his arm, and said to him suddenly — ”Uncle! Do you believe that the dead can come back to this world, and follow the living everywhere, and see what they do in it?”

The old man started. “Sarah!” he said, “why do you talk so? Why do you ask me such a question?”

“Are there lonely hours,” she went on, still never looking away from the corner, still not seeming to hear him, “when you are sometimes frightened without knowing why — frightened all over in an instant, from head to foot? Tell me, Uncle, have you ever felt the cold steal round and round the roots of your hair, and crawl bit by bit down your back? I have felt that even in the summer. I have been out of doors, alone on a wide heath, in the heat and brightness of noon, and have felt as if chilly fingers were touching me — chilly, damp, softly creeping fingers. It says in the New Testament that the dead came once out of their graves, and went into the holy city. The dead! Have they rested, rested always, rested forever, since that time?”

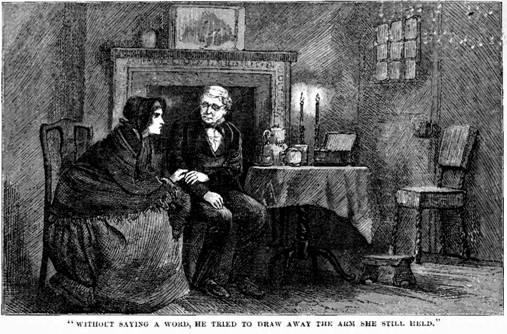

Uncle Joseph’s simple nature recoiled in bewilderment from the dark and daring speculations to which his niece’s questions led. Without saying a word, he tried to draw away the arm which she still held; but the only result of the effort was to make her tighten her grasp, and bend forward in her chair so as to look closer still into the corner of the room.