Complete Works of Wilkie Collins (213 page)

Read Complete Works of Wilkie Collins Online

Authors: Wilkie Collins

“I was in service a few days since,” she answered; “but I am free now. I have lost my place.”

“Aha! You have lost your place; and why?”

“Because I would not hear an innocent person unjustly blamed. Because — ”

She checked herself. But the few words she had said were spoken with such a suddenly heightened colour, and with such an extraordinary emphasis and resolution of tone, that the old man opened his eyes as widely as possible, and looked at his niece in undisguised astonishment.

“So! so! so!” he exclaimed. “What! You have had a quarrel, Sarah!”

“Hush! Don’t ask me any more questions now!” she pleaded earnestly. “I am too anxious and too frightened to answer. Uncle! this is Porthgenna Moor — this is the road I passed over, sixteen years ago, when I ran away to you. Oh! let us get on, pray let us get on! I can’t think of anything now but the house we are so near, and the risk we are going to run.”

They went on quickly, in silence. Half an hour’s rapid walking brought them to the highest elevation on the moor, and gave the whole western prospect grandly to their view.

There, below them, was the dank, lonesome, spacious structure of Porthgenna Tower, with the sunlight already stealing round toward the windows of the west front! There was the path winding away to it gracefully over the brown moor, in curves of dazzling white! There, lower down, was the solitary old church, with the peaceful burial-ground nestling by its side! There, lower still, were the little scattered roofs of the fishermen’s cottages! And there, beyond all, was the changeless glory of the sea, with its old seething lines of white foam, with the old winding margin of its yellow shores!

Sixteen long years — such years of sorrow, such years of suffering, such years of change, commuted by the pulses of the living heart! — had passed over the dead tranquillity of Porthgenna, and had altered it as little as if they had all been contained within the lapse of a single day!

The moments when the spirit within us is most deeply stirred are almost invariably the moments also when its outward manifestations are hardest to detect. Our own thoughts rise above us; our own feelings lie deeper than we can reach. How seldom words can help us, when their help is most wanted! How often our tears are dried up when we most long for them to relieve us! Was there ever a strong emotion in this world that could adequately express its own strength? What third person, brought face to face with the old man and his niece, as they now stood together on the moor, would have suspected, to look at them, that the one was contemplating the landscape with nothing more than a stranger’s curiosity, and that the other was viewing it through the recollections of half a lifetime? The eyes of both were dry, the tongues of both were silent, the faces of both were set with equal attention toward the prospect. Even between themselves there was no real sympathy, no intelligent appeal from one spirit to the other. The old man’s quiet admiration of the view was not more briefly and readily expressed, when they moved forward and spoke to each other, than the customary phrases of assent by which his niece replied to the little that he said. How many moments there are in this mortal life, when, with all our boasted powers of speech, the words of our vocabulary treacherously fade out, and the page presents nothing to us but the sight of a perfect blank!

Slowly descending the slope of the moor, the uncle and niece drew nearer and nearer to Porthgenna Tower. They were within a quarter of an hour’s walk of the house when Sarah stopped at a place where a second path intersected the main foot-track which they had hitherto been following. On the left hand, as they now stood, the cross-path ran on until it was lost to the eye in the expanse of the moor. On the right hand it led straight to the church.

“What do we stop for now?” asked Uncle Joseph, looking first in one direction and then in the other.

“Would you mind waiting for me here a little while, uncle? I can’t pass the church path — ” (she paused, in some trouble how to express herself) — ”without wishing (as I don’t know what may happen after we get to the house), without wishing to see — to look at something — ” She stopped again, and turned her face wistfully toward the church. The tears, which had never wetted her eyes at the first view of Porthgenna, were beginning to rise in them now.

Uncle Joseph’s natural delicacy warned him that it would be best to abstain from asking her for any explanations.

“Go you where you like, to see what you like,” he said, patting her on the shoulder. “I shall stop here to make myself happy with my pipe; and Mozart shall come out of his cage, and sing a little in this fine fresh air.” He unslung the leather case from his shoulder while he spoke, took out the musical box, and set it ringing its tiny peal to the second of the two airs which it was constructed to play — the minuet in Don Giovanni. Sarah left him looking about carefully, not for a seat for himself; but for a smooth bit of rock to place the box upon. When he had found this, he lit his pipe, and sat down to his music and his smoking, like an epicure to a good dinner. “Aha!” he exclaimed to himself, looking round as composedly at the wild prospect on all sides of him as if he was still in his own little parlor at Truro — ”Aha! Here is a fine big music-room, my friend Mozart, for you to sing in! Ouf, there is wind enough in this place to blow your pretty dance-tune out to sea, and give the sailor-people a taste of it as they roll about in their ships.”

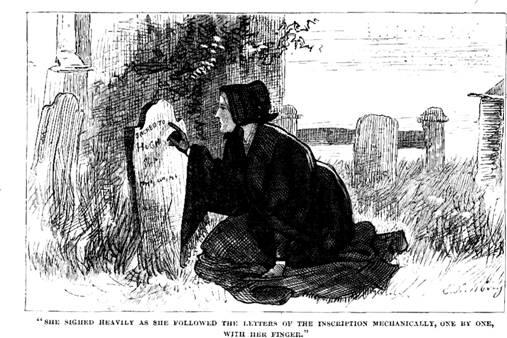

Meanwhile Sarah walked on rapidly toward the church, and entered the inclosure of the little burial-ground. Toward that same part of it to which she had directed her steps on the morning of her mistress’s death, she now turned her face again, after a lapse of sixteen years. Here, at least, the march of time had left its palpable track — its foot-prints whose marks were graves. How many a little spot of ground, empty when she last saw it, had its mound and its head-stone now! The one grave that she had come to see — the grave which had stood apart in the by-gone days, had companion graves on the right hand and on the left. She could not have singled it out but for the weather stains on the head-stone, which told of storm and rain over it, that had not passed over the rest. The mound was still kept in shape; but the grass grew long, and waved a dreary welcome to her as the wind swept through it. She knelt down by the stone, and tried to read the inscription. The black paint which had once made the carved words distinct was all flayed off from them now. To any other eyes but hers the very name of the dead man would have been hard to trace. She sighed heavily as she followed the letters of the inscription mechanically, one by one, with her finger:

SACRED TO THE MEMORY

OF

HUGH POLWHEAL

AGED 26 YEARS.

HE MET WITH HIS DEATH

THROUGH THE FALL OF A ROCK

IN

PORTHGENNA MINE,

DECEMBER 17TH, 1823.

Her hand lingered over the letters after it had followed them to the last line, and she bent forward and pressed her lips on the stone.

“Better so!” she said to herself; as she rose from her knees, and looked down at the inscription for the last time. “Better it should fade out so! Fewer strangers’ eyes will see it; fewer strangers’ feet will follow where mine have been — he will lie all the quieter in the place of his rest!”

She brushed the tears from her eyes, and gathered a few blades of glass from the grave — then left the churchyard. Outside the hedge that surrounded the inclosure she stopped for a moment, and drew from the bosom of her dress the little book of Wesley’s Hymns which she had taken with her from the desk in her bedroom on the morning of her flight from Porthgenna. The withered remains of the grass that she had plucked from the grave sixteen years ago lay between the pages still. She added to them the flesh fragments that she had just gathered, replaced the book in the bosom of her dress, and hastened back over the moor to the spot where the old man was waiting for her.

She found him packing up the musical box again in its leather case. “A good wind,” he said, holding up the palm of his hand to the fresh breeze that was sweeping over the moor — ”A very good wind, indeed, if you take him by himself — but a bitter bad wind if you take him with Mozart. He blows off the tune as if it was the hat on my head. You come back, my child, just at the nick of time — just when my pipe is done, and Mozart is ready to travel along the road once more. Ah, have you got the crying look in your eyes again, Sarah? What have you met with to make you cry? So! so! I see — the fewer questions I ask just now, the better you will like me. Good. I have done. No! I have a last question yet. What are we standing here for? why do we not go on?”

“Yes, yes; you are right, Uncle Joseph; let us go on at once. I shall lose all the little courage I have if we stay here much longer looking at the house.”

They proceeded down the path without another moment of delay. When they had reached the end of it, they stood opposite the eastern boundary wall of Porthgenna Tower. The principal entrance to the house, which had been very rarely used of late years, was in the west front, and was approached by a terrace road that overlooked the sea. The smaller entrance, which was generally used, was situated on the south side of the building, and led through the servants’ offices to the great hall and the west staircase. Sarah’s old experience of Porthgenna guided her instinctively toward this part of the house. She led her companion on until they gained the southern angle of the east wall — then stopped and looked about her. Since they had passed the postman and had entered on the moor, they had not set eyes on a living creature; and still, though they were now under the very walls of Porthgenna, neither man, woman, nor child — not even a domestic animal — appeared in view.

“It is very lonely here,” said Sarah, looking round her distrustfully; “much lonelier than it used to be.”

“Is it only to tell me what I can see for myself that you are stopping now?” asked Uncle Joseph, whose inveterate cheerfulness would have been proof against the solitude of Sahara itself.

“No, no!” she answered, in a quick, anxious whisper. “But the bell we must ring at is so close — only round there — I should like to know what we are to say when we come face to face with the servant. You told me it was time enough to think about that when we were at the door. Uncle! we are all but at the door now. What shall we do?”

“The first thing to do,” said Uncle Joseph, shrugging his shoulders, “is surely to ring.”

“Yes — but when the servant comes, what are we to say?”

“Say?” repeated Uncle Joseph, knitting his eyebrows quite fiercely with the effort of thinking, and rapping his forehead with his forefinger just under his hat — ”Say? Stop, stop, stop, stop! Ah, I have got it! I know! Make yourself quite easy, Sarah. The moment the door is opened, all the speaking to the servant shall be done by me.”

“Oh, how you relieve me! What shall you say?”

“Say? This — ’How do you do? We have come to see the house.’“

When he had disclosed that remarkable expedient for effecting an entrance into Porthgenna Tower, he spread out both his hands interrogatively, drew back several paces from his niece, and looked at her with the serenely self-satisfied air of a man who has leaped, at one mental bound, from a doubt to a discovery. Sarah gazed at him in astonishment. The expression of absolute conviction on his face staggered her. The poorest of all the poor excuses for gaining admission into the house which she herself had thought of and had rejected, during the previous night, seemed like the very perfection of artifice by comparison with such a childishly simple expedient as that suggested by Uncle Joseph. And yet there he stood, apparently quite convinced that he had hit on the means of smoothing away all obstacles at once. Not knowing what to say, not believing sufficiently in the validity of her own doubts to venture on openly expressing an opinion either one way or the other, she took the last refuge that was now left open to her — she endeavored to gain time.