Death to Tyrants! (50 page)

Authors: David Teegarden

The logical consequence of the cascading dynamic I just described would be the gradual creation of a common, Panhellenic, democratic culture that celebrates tyrant killing in defense of democracy, and thereby worked to lower the revolutionary thresholds among democracy supporters in the various cities. A level of cultural standardization or homogenization, that is, would emerge: tyrant killing and the use of public law (vel sim.) to make it a rational act becoming a common part of Greek democratic political culture. Thus, although the ideology and law type might have originated in Athens, it would become the property of Greek democrats everywhere. It would become the standard solution to the “defense of democracy” problem.

As noted above, my diffusion model and the effects thereof are by necessity hypothetical. But the following two points give it considerable support.

First, for well over two centuries following the promulgation of the decree of Demophantos, we find evidence for tyrant-killing ideology and/or tyrant-killing law when the survival of democracy is at stake. I have pointed out in this book significant examples: in Asia Minor shortly after the Peloponnesian War; on the mainland during the second and third quarters of the fourth century; on the mainland in response to Philip II's imperialism; in early Hellenistic Asia Minor. And there are other examples too. Timoleon's campaigns for “democracy” in Sicily during the third quarter of the fourth century, for example, were clearly configured as anti-tyranny or tyrant-killing campaigns.

4

And the leaders of the Achaean League from the mid-third to the early second century considered their enemies to be tyrants and were themselves prominent tyrant killers.

5

We thus have evidence for the type of Panhellenic

cultural standardization or homogenization that was predicted by my simple model.

Second, the “diffusion of institutions” dynamic I outlined with respect to tyrant-killing law is consistent with other episodes in ancient Greek history. This is particularly clear in the Archaic period, when institutions such as the alphabet, the hoplite phalanx, and coinage diffused through various areas of the Greek world, creating a certain decree of standardization in important domains of Greek culture.

6

And this dynamic is also evident in the Hellenistic period, when peer polity interactionsâthat is, the transmission of information between the citizens of the various statesâcontributed to the standardization of a large set of diplomatic formulae and protocols (e.g., those involved with

asylia

,

syngeneia

, and traveling judges), of dialect (i.e.,

koinÄ

), and practices such as euergetism and the epigraphic habitâto name just a few of the obvious examples.

7

Simply put, good ideas spread throughout the ancient Greek world and contributed to a common Greek culture. The invention and diffusion of tyrant-killing law and ideology was part of that characteristic phenomenon.

______________________

Tyrants, ancient as well as modern, fear the collective power of their people perhaps more than anything else. They have accordingly devised and implemented sophisticated practices that work to atomize the populationâto prevent the people from doing what they actually want to do. And most often they succeed: thus the rarity of democracy in world history. Over 2,400 years ago, however, the Athenians invented a toolâtyrant-killing lawâthat enabled pro-democrats to draw upon their collective strength and mobilize against nondemocratic regimes despite whatever anti-mobilization practices they might have implemented. And like great technological innovations throughout history, it spread as the citizens of other poleis adopted it in order to gain control of their own political destiny. That helped secure the world's first democratic age.

1

This is the conclusion of the author known as “the Old Oligarch.” See Ober (1998: 14â27) on this author and his assessment of the Athenian democracy's apparent invulnerability.

2

Thus Demosthenes (58.34) equates the annulment of the

graphÄ paranomÅn

with the overthrow (

katalusis

) of the

dÄmos

. On the

graphÄ paranomÅn

see also Lanni and Vermeule (2013), Schwartzberg (2013), and Teegarden (2013).

3

The emphasis here is on the word “decided.” I do not here describe a “contagion model” like that used to assess the spread (for example) of influenza. The diffusion of institutions is the result of an individual or individuals' conscious decision to adopt after having considered why it would be advantageous to do so.

4

See, for example, Plut.

Tim

. 24.1, 32.1. Plutarch also writes (

Tim

. 39) that the people of Syracuse buried Timoleon at public expense and conducted annual music and athletic contests in his honor “because he overthrew the tyrants.”

5

Margos of Karuneia killed the tyrant of Bura in 275/4 (Polyb. 2.41.14) and in 255 became the first sole holder of the office of

strategos

(Polyb. 2.43.2). Aratos of Sikyon was famous for his anti-tyranny policy and campaigns (e.g., Polyb. 2.44; Plut.

Arat

. 10.1). The people of Sikyon erected a bronze statue of him after he liberated them in 251 from the tyrant Nikokles. After Aratos died, they buried his body in the agora and conducted annual sacrifices to him on the day that he liberated their city (Plut.

Arat

. 53.3â4). Philopoimen, the last great leader of the league, personally killed the Spartan “tyrant” Machanidas in 207 at the battle of Mantinea (Polyb. 11.18.4). The Achaeans subsequently erected in Delphi a bronze statue of him in the act of killing the tyrant (Plut.

Phil

. 10.7â8,

Syll

.

3

625; Plut.

Phil

. 21.5,

Syll

.

3

624).

6

For general comments on the innovation and diffusion through the Greek world of the alphabet, hoplite phalanx warfare, and coinage, see Snodgrass (1980: 78â84, 99â107, 134â36).

7

On peer polity interactions in the Hellenistic period, see Ma (2003).

Appendix

The Number and Geographic Distribution of Different Regime

Types from the Archaic to the Early Hellenistic Periods

In the introduction I made significant assertions about the success of democracy within the larger ancient Greek world during the Archaic, Classical, and early Hellenistic periods. I here provide the data to support those assertions. In order to present the data within a more useful and compelling context, however, I also provide data on the success of other regime types during those same periods.

The data are culled exclusively from Hansen and Nielsen's

Inventory of Archaic and Classical Poleis

(2004), in particular from its appendix 11. I entered the data into a database that allows simple yet fundamental queries relating, most importantly, to the total number of cities for which we have regime-type information and the percentage of those cities that experienced the different regime-types in a particular period of time. The result, I believe, is a fairly compelling rough sketch of the relative success of the major regime types over several centuries.

I have not examined the evidential basis for all of the data that I included. Acknowledged experts wrote the entries for each of the poleis contained in the

Inventory

. If they suggest that city

x

experienced a democracy (or another regime type) in time

y

, I took their word at face value.

I have divided the data into periods of a half century. Using shorter units of time is unfortunately not practicable. There is one problem, however, in dividing the data even into periods of a half century. One of Hansen and Nielsen's temporal categories refers to the “middle” of a century, which corresponds to the forth to sixth decades of that century. For example, C7m (“middle of seventh century”) refers to the years 660â640, C4m refers to the years 360â340. Yet Hansen and Nielsen also have temporal categories that refer to the first or second half of a century. For example, C7f (“first half of seventh century”) refers to 699â650, while C7 (“second half of seventh century) refers to 649â600. Likewise C4f refers to 399â350, while C4 refers to 349â300. The difficulty (for this appendix) arises when there is evidence for a particular regime type in a city during the “middle” of the century, since that city could have experienced that regime during the first or the second

half of the century, or both. I have decided to have it refer to both halves of the century. Thus, for example, if there is evidence for democracy in city

x

in C4m, I mark it as experiencing democracy in both the first half and the second half of the fourth century.

I must also comment on what I mean by a city having “experienced” a particular regime type. First, that experience need not have been long in duration: if a democracy controlled city

x

for a month in, for example, C4f, that city experienced democracy in the first half of the fourth century. Second, a polis can experience several different regimes types in one half century. Thus the combined number of regime types experienced by all cities in a particular half century will be greater than the number of poleis for which we have regime type information for that half century; likewise, the sum of the percentages of cities experiencing all of the various regime types in a given half century will be greater than one hundred. For example, in a particular half century we might have regime-type information for ten cities, each of which experienced democracy, oligarchy, and tyranny. In that case there would thirty different regimes experienced by ten poleis, and the sum of the percentages of cities experiencing the various regime types for that half century would be 300: 100 percent experienced democracy, tyranny, and oligarchy.

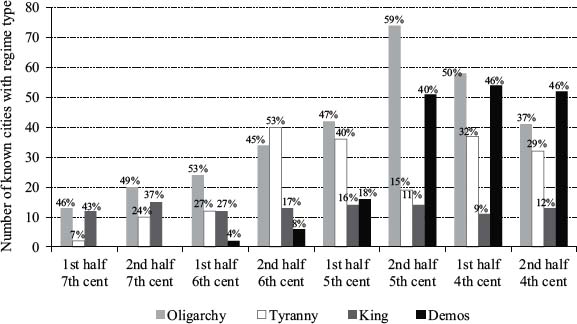

I here present two charts that efficiently capture the data.

Figure A1

indicates both how many cities are known to have experienced a particular regime type in a given half century and the percentage of cities known to have experienced that particular regime type during that half century (out of all cities for which we have regime-type information for that half century).

Figure A2

indicates the percentage of geographic regions known to have contained at least one city that experienced a particular regime type in a given half century. The two charts thus provide a decent basis to quickly gauge the success of a particular regime type over time. The more successful a regime type is, the greater the percentage of both cities and regions that experienced it.

I also include the raw data, organized by half century. The reader can thus assess for himself or herself the accuracy of my conclusions.

Numbers of Cities for Which Regime Type Data Are Available

FIRST HALF OF THE SEVENTH CENTURY

There is regime-type information for 28 different cities: Amathous, Argos, Athenai, Axos, Epidauros, Idalion, Istros, Kolophon, Korinthos, Kourion, Kroton, Kyme (in Italia), Lampsakos, Lapethos, Lokroi, Marion, Metapontion, Paphos, Paros, Rhegion, Salamis, Samos, Sikyon, Soloi, Sparta, Sybaris, Syrakousai, Taras. There is regime-type information for ten (out of thirty-

nine)

1

different regions: Cyprus, Argolis, Attica, Crete, Black Sea Area, Ionia, Megaris-Korinthia-Sikyonia, Italia and Kampania, the Aegean, Propontic Coast of Asia Minor.

Figure A1.

Regime type occurances over time.

Figure A2.

Regime type distributions over time.

OLIGARCHY

Thirteen cities are known to have experienced oligarchy: Athenai, Epidauros, Istros, Kolophon, Korinthos, Kroton, Kyme (in Italia), Lokroi, Metapontion, Paros, Rhegion, Sybaris, Syrakousai. Thus 46 percent of the cities for which there is regime-type information experienced an oligarchy.

Eight different regions contained at least one city governed by an oligarchy: Attika, Argolis, Black Sea Area, Ionia, Megaris-Korinthia-Sikyonia, Italia and Kampania, the Aegean, Sikelia. Thus 21 percent of the regions contained at least one city that was governed by an oligarchy.