Dennis Wheatley - Duke de Richleau 07 (10 page)

Read Dennis Wheatley - Duke de Richleau 07 Online

Authors: The Second Seal

“Knowing this,

surely the French will take the precaution to guard against such an

eventuality, by concentrating a large part of their army in the neighbourhood

of Amiens?”

The General

hesitated a second, then he said: “You will appreciate that I cannot give you

any definite information about the plans of the French General Staff. On the

other hand, I do not wish to mislead you as to possibilities. Both France and

Germany will require several weeks to complete their mobilization; but, owing

to various factors, there will be a period between the ninth and the thirteenth

day after the order for mobilization has been issued, when the French will have

been able to assemble a greater concentration of forces in the battle area than

the Germans. Certain French Generals have always urged that during this

favourable period France should seize the initiative and launch a full-scale

offensive against Alsace-Lorraine. Should they adopt that strategy, it is clear

that they will not have sufficient forces also to form a great concentration at

the western end of their line. But, of course, if their offensive farther east

proved successful, and they broke right through into Germany, that might compensate

for any temporary success that the Germans met with in north-eastern France.”

“I’ve always

thought,” put in Sir Bindon, “that the paper Winston Churchill wrote on that

subject at the time of the Agadir crisis summed up the possibilities brilliantly.

He was Home Secretary then, so quite outside all this sort of thing, but he was

invited to the secret meeting convened by the Prime Minister to hear the views

of the Service Chiefs. Later he produced a paper stressing these salient

points;”

“There would be

two periods at which the French could count on being equal, or possibly

superior, in numbers to the Germans, and so be in a favourable position to

launch an offensive. First, between the ninth and thirteenth day after

mobilization had begun. But, if they did so then, they would be bound to

encounter more and more fresh German formations as they advanced, and so soon

lose the initiative. Therefore, such an offensive was doomed to failure. He

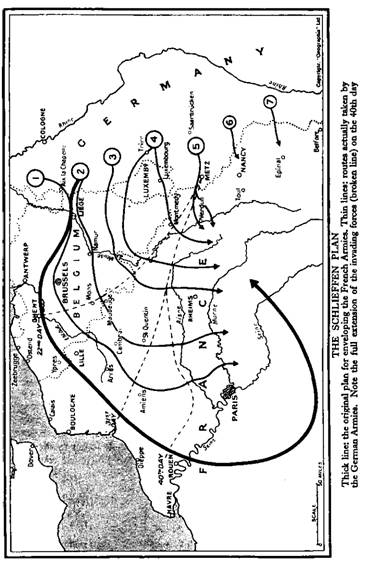

then forecast that, if the Schlieffen plan was adopted, by the twentieth day

after mobilization the Germans would have forced the line of the Meuse, and

that by the fortieth day they would be fully extended. He added that as their

lines of communication through Belgium lengthened they would have to detach

more and more troops to guard them; and that, therefore, by the fortieth day,

if the French had not dissipated their forces in the meantime, a second period

would arise when they would be equal, or possibly superior, to their enemies.

It was then that they should be able to launch their offensive with the best

hope of success.”

“Brilliant!”

muttered the Duke. “What amazing clarity of mind he possesses. I trust that the

French General Staff were suitably impressed.”

Sir Henry

laughed. “That is not for me to say. However, it gives you the alternative

strategy to an attack through Alsace-Lorraine, and we have good hopes that the

French will adopt it.”

“If they do not,

there is still a way by which the German sweep on Paris could be arrested.”

“I should be

most interested to hear it, Duke.”

“It is to land a

British Army at the French Channel ports, and deploy it to strengthen the

French left.”

Sir Bindon did

not flicker an eyelid, and the General’s laugh rang out quite naturally. They

were both past masters in the art of dissimulation where Britain’s vital

secrets were concerned. For years Sir Henry Wilson had spent all his leaves

cycling up and down the roads of Belgium and northern France, so that he might

know by heart every stream and contour of the country when the time came, as he

was convinced it would, to undertake that very operation. But half its value

would be lost if even a hint of our intentions reached the Germans.

“No, no, Duke!”

he protested. “That would be far beyond our capabilities. Think of the immense

difficulties with which we should be faced in organizing and transporting such

an Expeditionary Force— and the time it would take. The Germans would be half

way to Paris before we could even get started. Besides, how many divisions

could we put into the field? Four—six at the outside. They would be swallowed

up and lost in the general melee, and such a force could not possibly hope to

turn the tide of battle.”

He was using the

very arguments that the Naval Staff had used in 1911, when they had opposed the

War Office plan, and had maintained that the British Army should be retained at

home, as a striking force to be used later against Antwerp or the German coast,

as opportunity offered.

De Richleau

shrugged. “The British have a peculiar genius for organization, General, and in

an emergency are capable of acting with surprising speed; so I believe the

difficulties you refer to could be overcome. In such a case, too, it is not the

size but the high quality of the British Army that would count; and, above all,

the moral effect of such a stroke. Every French soldier would fight with

redoubled determination if he knew that British troops were facing the common

enemy with him.”

Now it was the

Duke who was using the arguments with which Sir Henry had got the better of the

sailors; but Britain’s leading strategist only shook his head again, and said a

trifle brusquely: “Can’t be done, Duke. Take it from me!”

“What use, then,

do you propose to make of the Army? Surely you do not intend to keep it here

indefinitely from fear of invasion?”

The General

grinned. “That’s a leading question, and one that I’m not prepared to answer.

We shall find a use for it in due course, never fear. But it’s going to take

time to build it up to a size at which it would be capable of intervening with

definite effect in a continental war; and to begin with great numbers of

regular officers and N.C.O. s will be needed to train the new levies. As for

invasion, we have little fear of that. Of course, the Navy can’t guarantee us

against enemy landings carried out on dark nights or during periods of fog; but

such raiding parties could have no more than a nuisance value. Within a few

hours they would find themselves cut oft”, and as soon as they ran out of

ammunition would be compelled to surrender. No major force with heavy equipment

would stand an earthly chance of getting ashore and establishing a permanent

foothold. I don’t pretend to know much about the Naval side of the picture, but

it is obvious that the French and British fleets combined will give us

overwhelming superiority at sea.”

For a minute

they were silent while again sipping their brandy. Then De Richleau asked, “What

views do you take of Russia’s prospects of making a deep penetration into

Germany, should she leave her eastern frontier comparatively open in order to

carry out the Schlieffen plan?”

“We’re not

counting very much on that,” Sir Henry replied, setting down his empty glass. “The

snag about Russia is the slowness of her mobilization. It may be several months

before she can bring her great masses face to face with the enemy. In the

meantime it is almost certain that a decision of sorts will have been reached

in the West, and we shall be entering a new phase of the war. In the worst

event, France will have shot her bolt and be on the defensive the wrong side of

Paris—or even out of the war. In the best, the French will be holding the

Germans on a line from Antwerp to Verdun. In either case the Germans should

have ample time to reinforce their eastern front before the Russian steamroller

really gets going.”

“There is, you

know, a second Schlieffen plan,” remarked Sir Bindon quietly. “Before he died,

Count Schlieffen saw the possibility of the Franco-Russian friendship

developing into a firm alliance, so that Germany might be faced with war on two

fronts simultaneously. Even then he would not allocate more than one-eighth of

the German forces to the Russian front; but he placed them skilfully. A glance

at the map will show you the Masurian Lakes. Situated in a vast tract of

impassable marshes, they form a chain sixty miles in length, having the

fortress of Lötzen in its centre, and running north-to-south about thirty miles

inside the East Prussian frontier. The Germans call it the Angerapp Line, and

von Schlieffen directed that the German Army of the East should deploy some way

behind it. He assumed, probably rightly, that the Russians would advance both

to the north and south of the barrier. Should they do so, the Germans would be

well placed to attack each of the invading forces in turn, and neither would be

able to give assistance to the other. In that way it is possible that the

Germans might defeat, or at least inflict a severe check on, forces double the

number of their own. And, of course, the initial effort of Russia against

Germany must be limited by the fact that she also has her Austrian front to

think of.”

De Richleau

nodded, glanced at the General, and asked “What strategy do you think Austria

is likely to adopt?”

“She has two

alternatives. She can stand on the defensive against Russia and make a maximum

effort against Serbia, with the object of putting her smaller enemy right out

of the war before coming to grips with her great antagonist. Or, she can devote

just sufficient troops to her southern front to hold Serbia in check while

launching the bulk of them in an immediate offensive against Russia.

Personally, I think her best course would be to adopt the second policy.” “Why?”

“In the first

place, because the factor of the comparative slowness of the Russian

mobilization enters into matters again. It is estimated that by M plus 18

Russia will have been able to muster on the Austrian front only thirty-one

divisions plus eleven cavalry divisions, against a probable Austrian

concentration of thirty-eight divisions plus ten cavalry divisions. So, you

see, if Austria strikes at once, her initial superiority in numbers should give

her a good prospect of gaining a victory which would paralyse Russian

activities on that front for some considerable time. There is also the factor

that an Austrian offensive against Serbia would be of no value as far as the

great over-all battle is concerned. Whereas an offensive against Russia would

almost certainly have the effect of lightening the Russian pressure on East

Prussia, thus making it unnecessary for the Germans to recall divisions from

France. To sum up, I think the second policy is not only to Austria’s own best

interests, but also the best service she could render to her ally; and it seems

obvious that Germany will press her to adopt it.”

“Your reasoning

is excellent, General,” smiled the Duke. “It seems, then, that there is little

hope of the Russians drawing any appreciable pressure off the French until the

first great clash is over.”

There fell

another pause. Sir Pellinore, who had long since learned the virtues of

refraining from pointless comments when experts were talking, had remained

silent for the past half an hour. He now leaned forward, stubbed out his cigar,

and said:

“Any more

questions, Duke?”

De Richleau

shook his handsome head. “No. I am most grateful to Sir Henry and Sir Bindon

for having discussed these matters so frankly with me. Except in certain minor

respects, the forecast they have given is not very far from that which my own

deductions would have led me to expect. But I considered it important to have

confirmation of my ideas. It would be of further assistance if I could be

supplied with the names of the officers who are expected to play a leading role

in the enemy armies, and such data as is available about them. In certain

circumstances such knowledge might prove very useful.”

“I’ll give you a

line of introduction to Maurice Hankey,” Sir Bindon offered. “He is the

Secretary of the Committee of Imperial Defence, and will be able to provide you

with all the information we possess on such matters.”

“Many thanks,

Sir Bindon. And the sooner I see him the better, as now I have agreed to

undertake this work, that also applies to my setting out for Serbia.”

Five minutes

later the four of them were walking from the entrance of the Club, down its

short garden path to the street. As they reached the pavement, and paused there

to say good-bye before going their several ways, an open motor-car, coming down

the hill from Carlton House Terrace, passed them.

In it were the

German Ambassador, Prince Lichnowsky, who had just left his Embassy, and Herr

Gustav Steinhauer, the Chief of the German Secret Service.