Dialogue (43 page)

Authors: Gloria Kempton

I'm a living example that this can happen. I'm sure, if I thought about it, I could think of many lines of dialogue that have in some way changed my life and made me a better, more loving person. But I can think of one for sure, used earlier in one of the excerpts in this book. It's Emma's words from Larry McMurtry's

Terms of Endearment

to her boys as she lay dying.

"... you're going to remember that you love me," Emma said. "I imagine you'll wish you could tell me that you've changed your mind, but you won't be able to, so I'm telling you now I already know you love me, just so you won't be in doubt about that later."

Emma is an unforgettable character to me because of this one moment where she gives her son, Tommy, the gift of knowing in these words. He's being ornery and his heart is closed to her. He's angry with her for dying. She's going past all of that to let him know that her knowing as a mother transcends his behavior and closed heart, that she knows deep down in his heart he loves her and while he's forgotten it right now, he'll remember it later.

I've taken Emma's words and have actually used them with my own grown son at this moment in time when he can't reach out, when his heart is closed to me. "I know that you love me," I've told him over and over again. "I know that you love me." It's my gift to him for this time in our relationship.

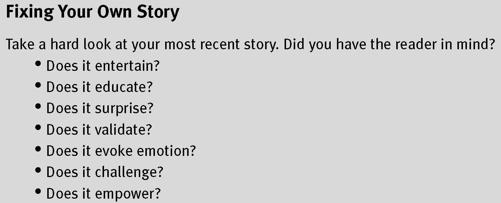

I tell you this story to let you know that you can create the kind of dialogue for your characters that your reader will remember, possibly forever. This is what I want to leave with you in this last chapter. To encourage you to, as much as is within you, make an emotional connection with your reader, to serve your reader in such a way that your dialogue will hit its mark in his heart. I've found a few ways to do that.

entertain the reader

As a writer, my mother loved to entertain, especially children. She would write the silliest stories. I remember the one about the man who lived in the crooked house. He would chat with those who came to call from his ceiling or one of the walls. She was skilled at the kind of conversational dialogue

that would make children laugh and laugh. She would capture them with her silly characters and keep them entertained for hours.

Then, in the late sixties and early seventies, something began to happen to, well, all kinds of fiction, but especially children's fiction. First of all, it began to disappear from magazines that had published it for years. But the other thing that happened was that editors began to request that their writers create the kind of fiction that incorporated a "lesson" into the story. The lesson could be about some aspect of children's health or it could be a moral truth, but editors no longer wanted talking animal stories or stories about crooked houses.

Something died inside of my mother that she never quite regained.

I'm personally pleased that the pendulum began to swing in the direction of fiction that actually says something, makes a point of some kind. But I also believe that our fiction can, and should, entertain. I believe that a skilled fiction writer communicates and entertains simultaneously. I'd like to suggest that one of the ways we can serve our readers is to write the kind of dialogue that entertains. This may not seem like such a radical idea, but it is when you consider that editors still want the kind of fiction that, while it entertains, is also "about" something.

When our fiction fails to communicate, our readers are no different after reading our stories. When our fiction fails to entertain, our readers won't stay with our stories long enough for us to communicate with them, and the end result is the same. No change.

At least one of our goals with dialogue should be to hold our reader by entertaining her, putting words in our characters' mouths that will make her laugh, cry, grow, think, smile, remember, feel, gasp, wring her hands, stomp her feet. In short,

move

her in some way. When a reader is entertained, she's relaxed and is open to the truths we want to get across in our characters' interactions with each other.

I like what I heard actor Sean Penn say recently on

Inside the Actors Studio.

He said that if we ever leave a movie theater feeling alone, the movie has failed to communicate its message. That's also true of a reader after putting down a novel.

educate the reader

While I don't think it's the primary task of the fiction writer to educate, learning can certainly take place for our readers when engaging with our characters' dialogue. Whether our characters are discussing life in other countries or life in prison, if it's a life our reader hasn't experienced, he learns something.

Ken Kesey's

One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest

had a profound effect on me when I read it just because I have no knowledge of what it's like to live in a mental institution. Kesey's novel is full of lively dialogue by quirky characters in a setting completely foreign to most of us. Whether it was Nurse Ratchett or one of the patients speaking, I was turning pages as fast as I could, fascinated with this setting that I knew nothing about. While there was plenty of educational narrative in this story, it was the dialogue that kept me hooked because it was through the dialogue that I really learned what these characters' lives were all about on a daily basis.

The same thing happened when I read Barbara Kingsolver's

The Poisonwood Bible

and Sue Monk Kidd's

The Secret Life of Bees.

Fictional dialogue brings unfamiliar settings to life on the page because dialogue is people.

And dialogue can educate the reader, not only about unfamiliar cultures or settings but also about human interaction because many of the characters in our stories relate to each other very differently than what the reader is used to. The reader learns that there is more than one way to argue, make love, or communicate one's feelings.

Our characters' dialogue can also educate readers about different historical settings. How much more fun to learn about the Civil War through the dialogue of two soldiers than to read a boring narrative history book.

surprise the reader

Readers love surprises. When your characters keep saying the same things to each other over and over and over again, the reader starts to yawn. I once worked with a writer who must have thought her character had a lot to say, and to a lot of different people. She wrote four restaurant scenes in a row where the protagonist sat down across the table from another character at yet one more restaurant—a different one each time—and poured her heart out. It wasn't just that the setting was the same, but the story this character told was the same.

Now that I think about it, you could actually take this scenario and make it surprise the reader. How? By having her tell a different story to each of the other characters about the same situation. This would surprise the reader because it would show what a liar this character was.

Often the character will say something that surprises even her. Or one of the other characters will say something to surprise all of us and to which your character will have a reaction that could be another surprise. Unpredictability in dialogue—that's what we're after.

Watch out for the tendency to create scenes where characters are simply regurgitating what has just happened in a scene of action. We already know what happened, so unless your character has something new to report, go on to the next scene. Often, after a scene of action, the viewpoint character will need to emotionally and mentally process the event, so you'll need to create a nondramatic scene of dialogue to let him do that. But even here, you'll want to show reactions through his dialogue that we don't expect from him. I don't mean reactions that are out of character, but maybe as he talks about his feelings and shares his thoughts with another character, he'll realize something about himself that he didn't know before or share feelings that he doesn't even understand himself. All of these kinds of elements in scenes of dialogue surprise the reader and keep her engaged.

validate the reader

If you validate your reader, he'll love you and read anything you write for the rest of his life. Yes, one of the reasons a reader chooses to read a story in the first place is because he needs validation. This is often on an unconscious level, but if your characters are sharing human emotions and thoughts that aren't always nice about other characters—especially those

about a wicked mother or mother-in-law—your reader will embrace your characters and embrace your story.

Readers think they're the only ones with these weird emotions and thoughts, sometimes violent, sometimes loving but toward the wrong people, sometimes inappropriate (to them) sadness. Then, your character is in the car talking to her husband and confesses that she's in love with his best friend. Or whatever. The reader identifies.

Dialogue that validates is dialogue that makes the reader feel okay about himself in a world full of normal people when he feels very abnormal. Validating dialogue in the mouths of your characters is dialogue that emotionally connects your reader to your characters so they truly will be unforgettable in her mind, the lessons learned lasting a very long time, maybe the rest of her life.

Validating dialogue lets the reader know that he's not alone, that he's part of a universal family, which remember, as Sean Penn said above, is what we're after.

cause the reader to feel

When we create real characters with real feelings about real situations in their lives, the reader is drawn into our story as if it's happening to her. This is how we know we're successful—when the reader so identifies and cares about your characters that she will feel joy, anger, sadness, fear, and all of the other emotions your characters feel as they move through the tragedies and comedies that are their lives.

If we want our readers to remember our characters and their stories, we need to evoke emotion. Think about your own life. The moments in your life that stand out in your mind are those you've experienced with the most emotion. It doesn't matter what the emotion was. Our feelings put us in the present moment, so when we put dialogue in our characters' mouths that plugs into a conversation the reader has had with someone or makes him think about something or someone that means a lot to him, we're creating one more unforgettable moment for him. In a sense, we're recreating his life for him that he's vicariously reliving through our characters.

This is just one more reason to create dialogue with substance. We may talk about nothing in our real lives, but when our characters talk about nothing, our readers aren't engaged with them on an emotional level. It's

only when the dialogue is

about

something that really matters that our readers' hearts begin to stir and before they know it, they're

in

the story, reacting to everything that's going on as if they're living it themselves.

This is our goal in writing dialogue that delivers: to engage our readers so they

feel

what our characters feel.

challenge the reader

Just as our characters challenge each other in their dialogue with one another, so do we want our readers to be challenged. When one character challenges another character to a duel, our reader feels an adrenaline rush. But that's an external challenge. Internally, we want to challenge our readers to change their lives if they need changing. We want to cause our readers to think about their lives in new ways. We want our readers to transcend old ways of thinking and believing that no longer fit who they are today. When our characters do this kind of work in their dialogue with each other, our reader does, too.

I don't mean sitting a character down in a therapy office. As long as we are committed to writing dialogue for our characters that matters, that has substance, that is

about

something, our readers will be challenged. How can they not be? If one of your characters suggests to another character that she might be addicted or abused or in some kind of illusion about some part of her life, don't you think your reader might wonder the same thing about her own life?

Challenging the reader is the work of literary and mainstream writers more than it is the work of genre writers. But still, even in genre stories, there are obstacles for the viewpoint character to overcome that should challenge the reader to overcome the same kinds of obstacles in her own life.