Dickinson's Misery (3 page)

Read Dickinson's Misery Online

Authors: Virginia; Jackson

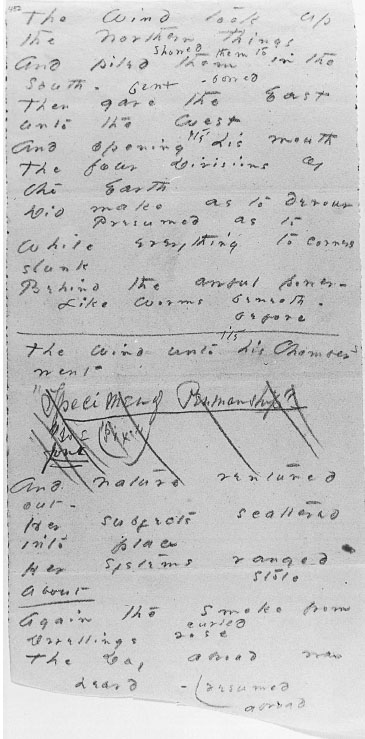

Figure 1. The text that Dickinson penciled on Mary Warner's penmanship practice sheet is now Franklin's poem 1152, “The wind took up the northern things.” Courtesy of Amherst College Archives and Special Collections (ED ms. 452).

Take for example the second number in the “authoritative diplomatic text” to which Cunningham referred, Thomas H. Johnson's

The Poems of Emily Dickinson: Including variant readings critically compared with all known manuscripts

. The poem is printed, with its comparative manuscript note, as follows:

2

There is another sky,

Ever serene and fair,

And there is another sunshine,

Though it be darkness there;

Never mind faded forests, Austin,

Never mind silent fieldsâ

Here is

a little forest,

Whose leaf is ever green;

Here is a brighter garden,

Where not a frost has been;

In its unfading flowers

I hear the bright bee hum;

Prithee, my brother,

Into

my

garden come!

MANUSCRIPT

: These lines conclude a letter, written on 17 October 1851, to her brother Austin. ED made no line division, and the text does not appear as verse. The line arrangement and capitalization of first letters in the lines are here arbitrarily established.

Once “arbitrarily established” as a lyric in 1955, these lines attracted a number of close readingsâthe response a lyric often invited after the middle of the twentieth century. By 1980, the lines had circulated for a quarter of a century as “a love poem with a female speaker,” which is to say that they were read according to a theory of their genre that included the idea of a fictive lyric persona.

5

Feminist criticism took up the problem of metaphorical gender in the lines, and several critics placed them back into the context of the letter to Austin, but after its publication as a lyric, the lines were not again interpreted (at least in print) as anything else (though they had been published as prose in 1894, 1924, and 1931âand were again published as a poem “in prose form” in Johnson's own edition of Dickinson's letters in 1958).

6

In 1998, Harvard issued a new edition of

The Poems of Emily Dickinson

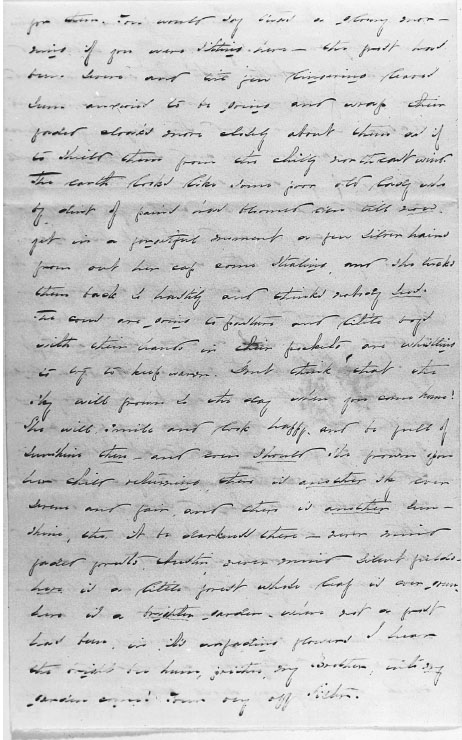

in both variorum and “reading” versions, now more authoritative and more diplomatic, thanks to the detailed textual scholarship of R. W. Franklin. Franklin's edition does not include the end of Dickinson's 1851 letter to her brother as one of the 1,789 poems in the reading edition, but he does list it in the variorum in an appendix of “some prose passages in Emily Dickinson's early letters [that] exhibit characteristics of verse without being so written” (F, 1578). As the manuscript of the letter attests (

fig. 2

), the lines were indeed not inscribed metrically, though they can certainly be read as a series of the three- and four-foot lines characteristic of Dickinson. Interestingly, Franklin prints the text as a series of such lines, thus printing what has been read rather than what was written, what may be interpreted rather than what may be describedâthough he also marks the difference between interpretation and description by making a section in his book for poems that he does not include as poems. Is the end of Dickinson's early letter, then, after 1998, no longer “a love poem with a female speaker”? Was it never such a poem, since it was never written as verse? Was it always such a poem, because it could always have been read as verse? Or was it only such a poem after it was printed as verse? Once read as a poem, can its generic reception be unprinted? Or is that interpretation so persistent that it survives even when the passage is not described as a poem?

Figure 2. Emily Dickinson to Austin Dickinson, 17 October 1851. The “poem” appears at the bottom of the page. Courtesy of Amherst College Archives and Special Collections (ED ms. 573, last page).

The many answers to these questions could be posed as statements about edition (the many ways in which Dickinson has been or could be published) or statements about composition (the many ways in which Dickinson wrote). While the fascinating historical details of Dickinson's production and reception will be central to this book, I will be primarily interested in what such details tell us about the history of the interpretation of lyric poetry (primarily in the United States) between the years that Dickinson wrote (most of the 1840s through most of the 1880s) and the years during which what she wrote has been printed, circulated, and read (from the middle of the nineteenth through the beginning of the twenty-first century). In view of what definition of poetry would Dickinson's brother have understood the end of his sister's letter to him as a poem? Did it only become a poem once it left his hands as a letter? According to what definition of lyric poetry did Dickinson's editor understand the passage as a lyric in 1955? What did Dickinson's editor in 1998 understand a lyric poem to be if it was not the passage at the end of the 1851 letter? Can a text not intended as a lyric become one? Can a text once read as a lyric be unread? If so, then what isâor wasâa lyric?

The argument of

Dickinson's Misery

is that the century and a half that spans the circulation of Dickinson's work as poetry chronicles rather exactly the emergence of the lyric genre as a modern mode of literary interpretation. To put briefly what I will unfold at length in the pages that follow: from the mid-nineteenth through the beginning of the twenty-first century, to be lyric is to be read as lyricâand to be read as a lyric is to be printed and framed as a lyric. While it is beyond the scope of this book to trace the lyricization of poetry that began in the eighteenth century, the exemplary story of the composition, recovery, and publication of Dickinson's writing begins one chapter, at least, in what is so far a largely unwritten history. As we have already begun to see, Dickinson's enduring role in that history depends on the ephemeral quality of the texts she left behind. By a modern lyric logic that will become familiar in the pages that follow, the (only) apparently contextless or sceneless, even evanescent nature of Dickinson's writing attracted an increasingly professionalized attempt

to secure and contextualize it as a certain kind (or genre) of literatureâas what we might call, after Charles Taylor, a lyric social imaginary.

7

Think of the modern imaginary construction of the lyric as what allows the term to move from adjectival to nominal status and back again. Whereas other poetic genres (epic, poems on affairs of state, georgic, pastoral, verse epistle, epitaph, elegy, satire) may remain embedded in specific historical occasions or narratives, and thus depend upon some description of those occasions and narratives for their interpretation (it is hard to understand “The Dunciad,” for example, if one does not know the characters involved or have access to lots of handy footnotes), the poetry that comes to be understood as lyric after the eighteenth century is thought to require as its context only the occasion of its reading. This is not to say that there were not ancient Greek and Roman, Anglo-Saxon, medieval, Provençal, Renaissance, metaphysical, Colonial, Republican, Augustanâeven romantic and modern!âlyrics. It is simply to propose that the riddles, papyrae, epigrams, songs, sonnets,

blasons

,

Lieder

, elegies, dialogues, conceits, ballads, hymns and odes considered lyrical in the Western tradition before the early nineteenth century were lyric in a very different sense than was or will be the poetry that the mediating hands of editors, reviewers, critics, teachers, and poets have rendered as lyric in the last century and a half.

8

As my syntax indicates, that shift in genre definition is primarily a shift in temporality; as variously mimetic poetic subgenres collapsed into the expressive romantic lyric of the nineteenth century, the various modes of poetic circulationâscrolls, manuscript books, song cycles, miscellanies, broadsides, hornbooks, libretti, quartos, chapbooks, recitation manuals, annuals, gift books, newspapers, anthologiesâtended to disappear behind an idealized scene of reading progressively identified with an idealized moment of expression. While other modesâdramatic genres, the essay, the novelâmay have been seen to be historically contingent, the lyric emerged as the one genre indisputably literary and independent of social contingency, perhaps not intended for public reading at all. By the early nineteenth century, poetry had never before been so dependent on the mediating hands of the editors and reviewers who managed the print public sphere, yet in this period an idea of the lyric as ideally unmediated by those hands or those readers began to emerge and is still very much with us.

Susan Stewart has dubbed the late eighteenth century's highly mediated manufacture of the illusion of unmediated genres a case of “distressed genres,” or “new antiques.” Her terms allude to modern print culture's attempts “to author a context as well as an artifact,” and thus to imitate older formsâsuch as the epic, the fable, the proverb, the balladâwhile

creating the impression that our access to those forms is as immediate as it was in the imaginary modern versions of oral and collective culture to which those forms originally belonged.

9

Stewart does not include the lyric as a “distressed genre,” but her suggestion that old genres were made in new ways could be extended to include the idea that the lyric isâor wasâa genre in the first place. As Gérard Genette has argued, “the relatively recent theory of the âthree major genres' not only lays claim to ancientness, and thus to an appearance or presumption of being eternal and therefore self-evident,” but is itself the effect of “projecting onto the founding text of classical poetics a fundamental tenet of âmodern' poetics (which actually ⦠means

romantic

poetics).”

10

Yet even if the lyric (especially in its broadly defined difference from narrative and drama) is a larger version of the new antique, a retro-projection of modernity, a new concept artificially treated to appear old, the fact that it is a figment of modern poetics does not prevent it from becoming a creature of modern poetry. The interesting part of the story lies in the twists and turns of the plot through which the lyric imaginary takes historical form. But what plot is that? My argument here is that the lyric takes form through the development of reading practices in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries that become the practice of literary criticism. As Mark Jeffreys eloquently describes the process I am calling lyricization, “lyric did not conquer poetry: poetry was reduced to lyric. Lyric became the dominant form of poetry only as poetry's authority was reduced to the cramped margins of culture.”

11

This is to say that the notion of lyric enlarged in direct proportion to the diminution of the varieties of poetryâor at least that became the ratio as the idea of the lyric was itself produced by a critical culture that imagined itself on the definitive margins of culture. Thus by the early twenty-first century it became possible for Mary Poovey to describe “the lyricization of literary criticism” as the dependence of all postromantic professional literary reading on “the genre of the romantic lyric.”

12

The conceptual problem is that if the lyric is the creation of print and critical mediation, and if that creation then produces the very versions of interpretive mediation that in turn produce it, any attempt to trace the historical situation of the lyric will end in tautology.

Or that might be the critical predicament if the retrospective definition and inflation of the lyric were either as historically linear or as hermeneutically circular as much recent criticism, whether historicist or formalist, would lead us to believe. What has been left out of most thinking about the process of lyricization is that it is an uneven series of negotiations of many different forms of circulation and address. To take one prominent example, the preface to Thomas Percy's

Reliques of Ancient English Poetry

(1765) describes the “ancient foliums in the Editor's possession,” claims to

have subjected the excerpts from these manuscripts to the judgment of “several learned and ingenious friends” as well as to the approval of “the author of

The Rambler

and the late Mr. Shenstone,” and concludes that “the names of so many men of learning and character the Editor hopes will serve as amulet, to guard him from every unfavourable censure for having bestowed any attention on a parcel of Old Ballads.”

13

Not only does Percy not claim that historical genres of verse are directly addressed to contemporary readers (and each of his “relics” is prefaced by a historical sketch and description of its manuscript context in order to emphasize the excerpt's distance from the reader), but he also acknowledges the role of the critical climate to which the poems in his edition

were

addressed.

14

Yet by 1833, John Stuart Mill, in what has become the most influentially misread essay in the history of Anglo-American poetics, could write that “the peculiarity of poetry appears to us to lie in the poet's utter unconsciousness of a listener. Poetry is feeling confessing itself to itself, in moments of solitude.”

15

As Anne Janowitz has written, “in Mill's theory ⦠the social setting is benignly severed from poetic intentions.”

16

What happened between 1765 and 1833 was not that editors and printers and critics lost influence over how poetry was presented to the public; on the contrary, as Matthew Rowlinson has remarked, in the nineteenth century “lyric appears as a genre newly totalized in print.”

17

And it is also not true that the social setting of the lyric is less important in the nineteenth than it was in the eighteenth century. On the contrary, because of the explosion of popular print, by the early nineteenth century in England, as Stuart Curran has put it, “the most eccentric feature of [the] entire culture [was] that it was simply mad for poetry”âand as Janowitz has trenchantly argued, such madness extended from the public poetry of the eighteenth century through an enormously popular range of individualist, socialist, and variously political and personal poems.

18

In nineteenth-century U.S. culture, the circulation of many poetic genres in newspapers and the popular press and the crucial significance of political and public poetry to the culture as a whole is yet to be appreciated in later criticism (or, if it is, it is likely to be given as the reason that so little enduring poetry was produced in the United States in the nineteenth century, with the routine exception of Whitman and Dickinson, who are also routinely mischaracterized as unrecognized by their own century).

19