Dickinson's Misery (4 page)

Read Dickinson's Misery Online

Authors: Virginia; Jackson

At the risk of making a long story short, it is fair to say that the progressive idealization of what was a much livelier, more explicitly mediated, historically contingent and public context for many varieties of poetry had culminated by the middle of the twentieth century (around the time Dickinson began to be published in “complete” editions) in an idea of the lyric as temporally self-present or unmediated. This is the idea aptly expressed

in the first edition of Brooks and Warren's

Understanding Poetry

in 1938: “classifications such as âlyrics of meditation,' and âreligious lyrics,' and âpoems of patriotism,' or âthe sonnet,' âthe Ode,' âthe song,' etc.” are, according to the editors, “arbitrary and irrational classifications” that should give way to a present-tense presentation of “poetry as a thing in itself worthy of study.”

20

Not accidentally, as we shall see, the shift in definition accompanied the migration of lyric from the popular press to the classroomâbut for now we should note that by the time that Emily Dickinson's poetry became available in scholarly editions and university anthologies, the history of various genres of poetry was read as simply lyric, and lyrics were read as poems one could understand without reference to that history or those genres.

The first and second chapters of this book will trace the developing relation between lyric reading and lyric theory in the United States over the nineteenth and twentieth centuries by focusing on the circulation and reception of Dickinson's remains. What makes Dickinson exemplary for a history of the lyric in which I wish to chronicle a shift in the definition (or undoing) of the genre as an interpretive abstraction is that there is so little left of her. Yet, as we shall also see, the persistent sense that something

is

leftâthose handsewn leaves, those pieces of envelopes pinned at odd anglesâkeeps recalling modern readers to an archaic moment of handwritten composition and personal encounter, a private moment yet unpublicized, a moment before or outside literature that also becomes essential to modern lyric reading in post-eighteenth-century print culture.

21

As Yopie Prins has written, “if âreading lyric' implies that lyric is already defined as an object to be read, âlyric reading' implies an act of lyrical reading, or reading lyrically, that poses the possibility of lyric without presuming its objective existence or assuming it to be a form of subjective expression.”

22

This is as much as to say that while any literary genre is always a virtual object, there may be ways to read the history of a genre on the way to becoming such an object. Still, as Prins implies, the object that the lyric has become is by now identified with an expressive theory that makes it difficult for us to place lyrics back into the sort of developmental historyâof social relations, of print, of edition, reception, and criticismâthat is taken for granted in definitions of the novel.

23

The reading of the lyric produces a theory of the lyric that then produces a reading of the lyric, and that hermeneutic circle rarely opens to dialectical interruption. In his famous version of “lyric reading,” Paul de Man cast such an interruption as theoretically impossible: “no lyric can be read lyrically,” according to de Man, “nor can the object of a lyrical reading be itself a lyric.”

24

While this is as much as to say (as de Man went on to say) that “the lyric is not a genre” (261) in theory,

Dickinson's Misery

shows how

poems become lyrics in history. Once we decide that Dickinson wrote poems (or once that decision is made for us), and once we decide that most poems are lyrics (or once that decision is made for us), we (by definition) lose sight of the historical process of lyric reading that is the subject of this book. Precisely because lyrics can only exist theoretically, they are made historically.

Since most of that historical process has taken place in relation to Dickinson in the United States, the subtitle of this book could be “American Lyric Reading,” but it is not the national identity of the lyric imaginary that Dickinson comes to represent that I want to emphasize here. As we shall see, for over a century readers of Dickinson have been preoccupied with her work's exemplary American character, and that aspect of the public imagination of Dickinson will be central to the pages that follow. There

is

an account of the lyricization of specifically American poetry to be written, especially since there has been no comprehensive view of that history since Roy Harvey Pearce's

The Continuity of American Poetry

in 1961. Pearce takes for granted that Puritan epitaphs, elegies, anagrams and meditations, Republican epics, satires, dialogues in verse, pedagogical exercises, versified commencement addresses, protest songs, contemporary ballads, odes, and commemorative recitation exercises can all be read as lyricsâindeed, one might argue that it is lyric reading that makes possible the “continuity” of Pearce's title. Such a close affiliation between lyricization and Americanization will come to seem familiar in these chapters, though there is much to be said about the relation between national and generic identity that will fall outside the chapters themselves. I will be arguing that while the national as well as the gendered, sexed, classed, and (just barely) raced identities at play in Dickinson's writing have been examined to different ends in recent criticism, the generic lens they must all pass through has been treated as transparent.

25

This book attempts to make the only apparently transparent genre through which Dickinson has been brought into public view itself visible. Some of the work of doing so might at times seem microscopic, since it entails a focus not on big ideasâpoetry, America, person- and womanhoodâbut on the small details on which those ideas precariously (though surprisingly tenaciously) depend.

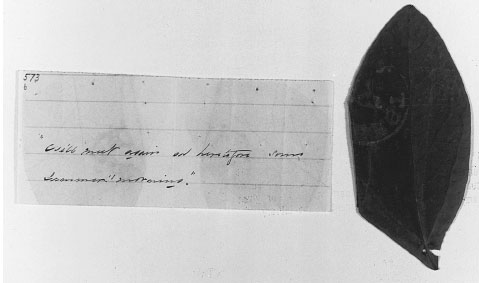

Consider, for example, one overlooked detail in the history of reading Dickinsonâa bit of ephemera that tempts while it also resists lyric reading. Like so many of Dickinson's letters, the rather long 1851 letter to Austin that closes with the lines that Johnson “arbitrarily established” in 1955 as a lyric and that Franklin then decided were not a lyric contained an enclosure: a leaf pinned to a slip of paper inscribed “We'll meet again and heretofore some summer âmorning'” (

fig. 3

). The “little forest, whose leaf is ever green” to which the lines-become-verse point is and is not the leaf that Austin held in his hand, and that difference is the enclosure's point. Whether or not the lines at the end of the letter are printed as a lyric, the now-faded leaf that left its imprint on the line attached to those lines cannot be printedâthough it is here, for the first time, reproduced, and thus unfolded from Dickinson's letter and folded into the genre of literary criticism. Now addressed not to Austin but to my anonymous reader (to you), not the leaf itself but a copy of its remains, Dickinson's enclosure becomes legible as a detail of a literary corpus. Or does it? While for Austin the leaf popped out of the letter as an ironic commentary on the time and place the familiar correspondents did not but may yet have shared (if only on the page, or between quotation marks) on the October day when the letter was sent (“some summer âmorning'”), by the time that you (whoever you are) encounter the image of the leaf in this book about Dickinson you will understand it instead as a reminder of what you cannot share with Dickinson's first readers, an overlooked object lyrically suspended in time. What may seem lyrical about it is the apparent immediacy of our encounter with it: editors and printers and critics and teachers may have transformed Dickinson's work into something it was not intended to be, but a leaf is a leaf is a leaf. Yet Dickinson's message pinned to the leaf asks its intended reader to understand that a leaf taken out of context is not self-defining; it won't remain “ever green” but will (as it has) fade to

brown. Dickinson could not have foreseen that the faded leaf would end up in a college library, or that her intimate letter to her brother would one day be addressed to the readers of the 1955

Complete Poems of Emily Dickinson

. She could also not have foreseen that the leaf in the library would bear the trace of its transmission stamped by a hand not Dickinson's nor any reader's own.

Dickinson's Misery

is about the way in which the confusion between the pathos of a subject and the pathos of transmission evoked by the leaf rather accurately predicts the character of the poet who will come to be read heretofore as Emily Dickinson. This book is also about the way in which that confusion has come to define, in the last century and a half, not only an idea of what counts as Dickinson's verse but of what does and does not count as literary languageâand especially of what does and does not count as lyric language. Let the postmark on the leaf that mediated the encounter between Dickinson and her intimate reader also stand for the institutions that exceed as they deliver literatureâmodes of cultural transmission that make even an old leaf legible.

Figure 3. Emily Dickinson to Austin Dickinson, 17 October 1851. The postscript was pinned where the hole appears in the leaf at the bottom of the picture; the postmark on the leaf matches the postmark on the envelope that contained it. Courtesy of Amherst College Archives and Special Collections (ED ms. 573, enclosure).

My title,

Dickinson's Misery

, is intended to gain significance as this book progresses. As my account of the historical transmission of Dickinson's writing takes us further and further away from a direct encounter with that writing, “Dickinson's Misery” may evoke the pathos not of Dickinson herself but of her writing as a lost object, a

texte en souffrance

.

26

Yet while Derrida may be right that writing always goes astrayâor is, by definition, disseminated in order to become literatureâ

published

writing does not wander away on its own: it is directed and addressed by some to others. In my first chapter, “Dickinson Undone,” I will consider recent editorial attempts to release Dickinson's writing from the constraint of earlier editorial conventions and to rescue the character of that writing from institutional mediationâeven from the constraint of the codex book itself. I will argue that recent attempts to liberate Dickinson from the unfair treatment of editorial hands are dependent on an imaginary model of the lyricâa model perhaps more constraining, because so much more capacious, than those Dickinson's early genteel editors supposed. The aspects of Dickinson's writing that do not fit into any modern model of the lyricâverse mixed with prose, lines written in variation, or lines (like the one pinned to the leaf) dependent on their artifactual contextsâhave been left to suffer under the weight of variorum editions or have been transformed into weightless, digitized images of fading manuscripts made possible by invisible hands. In my second chapter, I will measure the distance between the circulation of Dickinson's verse in several spheres of familiar and public culture in the nineteenth century and the circulation of ideas of the lyric in academic culture in the twentieth century. The more we know about the circumstances of the nineteenth-century composition and reception of

Dickinson's poems, the less susceptible they seem to the theories of lyric abstraction that emerged in twentieth-century critical culture. From genteel criticism to New Criticism to de Man's lyric theory to the pragmatic backlash against literary theory and the new lyric humanism, ideas of the lyric in the century during which Dickinson's work proliferated in print constructed and deconstructed the genre in which Dickinson's writing has been cast, but in doing so they tended to widen rather than close the distance between that genre and that writing. The remaining chapters then attempt to bridge that distance, or to claim that Dickinson's work may help us to do so. In my third chapter, I will compare Dickinson's figures of addressâher sociable correspondenceâto the forms of address that have been attributed to her texts as a set of lyrics. In my fourth chapter, I will explore Dickinson's forms of self-reference, especially literal or physical self-reference, in the context of nineteenth-century American intellectual culture and in the context of twentieth-century feminist discourse. In my final chapter, I will bring those modern feminist concerns to bear upon the nineteenth-century sentimental lyric, an often forgotten genre of vicarious identification that itself may span the distance between Dickinson's writing and the image of the poet she has become. In all of the chapters, my concern will be to trace the arc of an historical poetics, a theory of lyric reading, that seeks to revise not only our understanding of Dickinson's work but our contemporary habits of poetic interpretation.

Dickinson's Misery

tries to do many things, but one thing it does not try to be is a reception history. Scholars have already compiled excellent critical histories of Dickinson's reception, though there is much more to be done, especially on the history of Dickinson's popular readership, yet that is not my project in this book.

27

Here I am interested instead in the models of the lyric that governed Dickinson's edition and reception. I could have chosen to chronicle those models strictly chronologicallyâthe aesthetic model of the 1890s, the Imagist model of 1914, the modernist model of the 1920s, the culturally representative model of the 1930s, the pedagogical model of the 1940s, the professional model of the 1950s, the subversive model of the 1960s, the conflicted model of the 1970s, the feminist model of the 1980s, the materialist and queer models of the 1990s, and the public sphere and cyberspace models of the beginning of the twenty-first centuryâbut as this list suggests, such a chronology quickly devolves into a thematic catalogue of types of lyrics while leaving the generic character of those lyrics relatively stable. This book instead combines reception history, book history, literary history, genre theory, and one genealogy of the discipline of literary criticism to destabilize an idea of the genre of which Dickinson's work has become such an important modern paradigm. Editors, reviewers, teachers, and readers may make up versions of a genre to

suit their place and time, but they do not do so from scratch. My subtitle, “A Theory of Lyric Reading,” is meant to suggest that genre is neither an Aristotelian, taxonomic, transhistorical category of literary definition nor simply something we make up on the spot to suit the occasion of reading. What a reading of Dickinson over and against the generic models through which she has been published and read can tell us about the lyric as a genre is indeed that history has made the lyric in its image, but we have yet to recognize that image as our own.