Dickinson's Misery (5 page)

Read Dickinson's Misery Online

Authors: Virginia; Jackson

Dickinson Undone

B

IRD-TRACKS

I

N OCTOBER

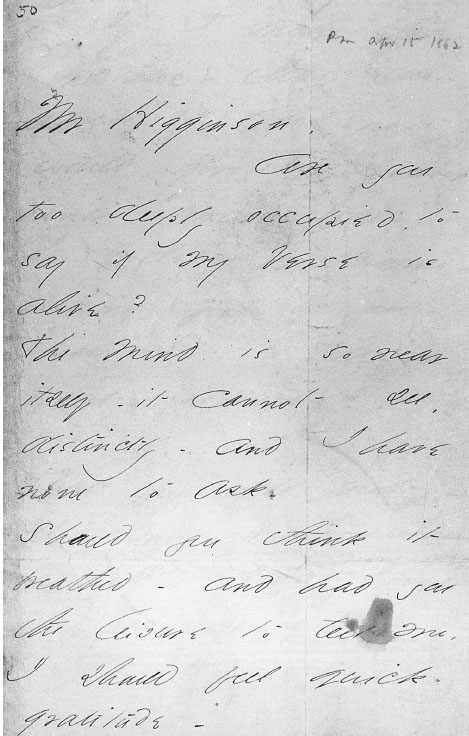

1891, Thomas Wentworth Higginson published an article that may be read as a miniature portrait of Dickinson's reception as a lyric poet. The article, not ostensibly on the poetry but on “Emily Dickinson's Letters,” responded to what Higginson called “a suddenness of success almost without a parallel in American literature” (that is, the commercial success of his own first edition of Dickinson's

Poems

the year before) by making public the poet's private letters to her future literary editor. After printing the first one (

figs. 4a

,

4b

), from April, 1862, which (now) famously begins,

MR. HIGGINSON

â

Are you too deeply occupied to say if my verse is alive?

,

Higginson remarks in the

Atlantic

article, “The letter was postmarked “Amherst,” and it was in a handwriting so peculiar that it seemed as if the writer might have taken her first lessons by studying the famous fossil bird-tracks in the museum of that college town.” Dickinson's inaugural letter to Higginson has been remembered and reprinted so often that her self-introduction to the abolitionist, women's rights activist, former Longfellow student at Harvard, magazine editor, and literary insider now appears to have been addressed to us. Yet Higginson is the one who makes the letter seem to have been publicly addressed to a private individual rather than privately addressed to a public figure when he invents a story about his own encounter with unfamiliar writing: according to this story, first the reader notices the postmark on the envelope, then the character of the hand (which was not actually yet “so peculiar” in 1862), and then he puts the two together. By way of this anecdote, Dickinson's editorâwhom she had addressed as her “Preceptor” in response to Higginson's own public letter “To a Young Contributor” in that month's

Atlantic

âmakes his mediating role in the recognition of Dickinson's poetry as American literature disappear.

1

The interest that by the time of Higginson's 1891 article readers had already demonstrated by buying out six printings of Dickinson's

Poems

in the volume's first six months of publication (a phenomenon much publicized at the time in several citiesâas one E. J. Edwards remarked after noting that it was impossible to buy a copy of the

Poems

in

New York a few days before Christmas, 1890) is presupposed in Higginson's fable of a first, innocent encounter with Dickinson's handwriting.

2

What Higginson also supposed in that first encounter and what every reader since Higginson has assumed is that what Emily Dickinson wrote was lyric poetry. But how do we know that lyrics are what Dickinson wrote? What definition of the lyric turns words on an envelope into a poem?

Although he goes on to claim that “the impression of a wholly new and original poetic genius was as distinct on my mind at the first reading ⦠as it is now,” it was the public demand for more information in print that occasioned the editor's rendition of his first impression. By the time that Higginson told his story of trying to decipher Dickinson's peculiar hand, Mabel Loomis Todd had already transcribed and carefully copied and Roberts Brothers had typeset and many booksellers had sold many volumes of Dickinson's verse. It is thus possible to say that in Higginson's narrative, print precedes handwriting: the story he weaves about Dickinson's manuscript is really a story about the poems already in print.

3

Yet print is not the only defining feature of Dickinson's writing in Higginson's account: his fable of the identity between that writing and the spirit of its place makes writing seem to precede what it represents. In this fiction, Emily Dickinson learned to write not at Amherst Academy or Mount Holyoke Seminary but in the museum of the college her family helped to establish. The product of an institution within an institution, Dickinson's originality appears to Higginson a copy of a prehistoric natural formâa form that was, not incidentally, the trace of the figure of the bird that Dickinson (and almost everyone else in the nineteenth century) associated with lyricism. Subtle and fanciful as Higginson's imaginary scenario may be, it is also an image of Dickinson's lyric receptionâa reception that Higginson figures as already encrypted in Dickinson's writing, fixed into timeless generic form and rescued, excerpted, and placed on public display by a private cultural institution.

Higginson's edition, criticism, and promotion of Dickinson has been much criticized by later editors, critics, and promoters of Dickinson. Either Higginson is accused of failing to recognize Dickinson's greatness by not bringing her into print during her lifetime, or he is accused of having made the volume he did publish posthumously an image of his own idea of what Dickinson's poems should have been. Most readers would agree that Dickinson's early editors imposed conventional poetic formâincluding titles, regular rhyme, and standard punctuationâon the published verse that in manuscript evaded or swerved away from such conventions, and most would also agree that editors since Higginson have brought Dickinson's published work ever closer to its original scriptive forms, so that in moving forward from the nineteenth to the twentieth to the twenty-first century we have gradually moved back to discover the “original poetic genius” early editors failed adequately to represent in print. Increasingly, that revelation has taken the cast of what Mary Loeffelholz has called “the unediting of Dickinson,” a growing fascination over the last decades (after R. W. Franklin's publication of

The Manuscript Books of Emily Dickinson

in 1981) with the details of Dickinson's handwriting and with the ready-to-hand artifacts on which she wrote. “The full significance of Dickinson's writing,” Jerome McGann predicted in 1991, “will begin to appear when we explicate in detail the importance of the different papers she used, her famous âfascicles,' her scripts and their conventions of punctuation and layout.”

4

Yet as editors and critics have returned their attention to Dickinson's papers bound and unbound, to her peculiar hand, and to the “layout” between the two, the question lurking in Higginson's 1891 description of Dickinson's manuscript has resurfaced: what was it that Emily Dickinson wrote?

Figure 4a. Emily Dickinson to Thomas Wentworth Higginson, April 1862. Boston Public Library/Rare Books Department, Courtesy of the Trustees (Ms. AM 1093, 1).

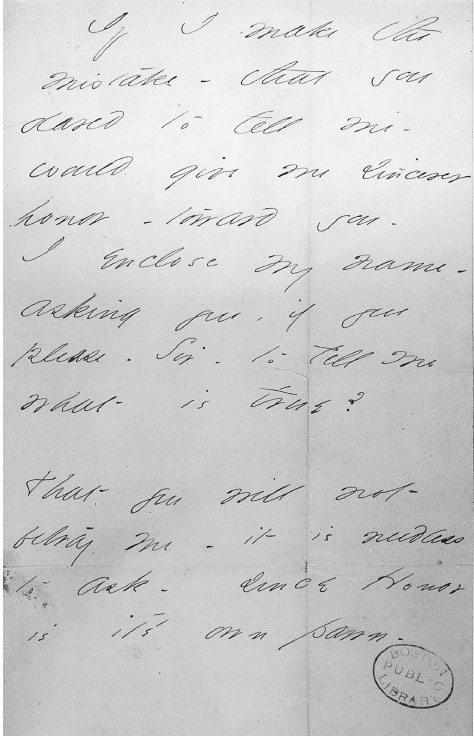

Figure 4b. Emily Dickinson to Thomas Wentworth Higginson, April 1862. Boston Public Library/Rare Books Department, Courtesy of the Trustees (Ms. AM 1093, 1).

Higginson's image of fossilized bird-tracks contains a (rather beautiful) notion of the lyric as the form informing Dickinson's scriptive characterâa very late-nineteenth-century image of lyric reading. Later editors have certainly come a long way since Higginson, and the lyrics they decipher in Dickinson's manuscripts have changed character, yet although at the time of this writing many debates rage over the literary forms immanent in Dickinson's writing, there is and always has been uniform consensus that Emily Dickinson wrote lyric poems. While versions of Dickinson's lyricism have shifted as interpretive communities have shifted, some version of the genre everyone since Higginson has assumed Dickinson wanted her writing to become has been discovered to be already there. Like Higginson in 1891, most readers have found it impossible to read Dickinson's manuscripts as if they had not already been printed as poems. Yet Higginson

had

read just such manuscriptsâand had not, until Dickinson's death, printed her work as a series of poems. Did Higginson not recognize a poem when he saw one? If we imagine the now historically impossible scenario (conjured on the first page of this book) of “discovering” Dickinson's as yet unprinted manuscripts, would we recognize a Dickinson poem if we saw one?

For the moment I would like to set aside strictly formal answers to that question. Hymnal meter, the occasional pentameter line, stanzaic breaks, regular and irregular rhymes, and rhetorical patterns define much of Dickinson's writing as

poetic

in a very broad sense of the termâin the broadest sense, as language not unversified. Many manuscriptsâespecially the “fascicles,” or hand-sewn booklets, but also such separate sheets as the

ones Dickinson enclosed to Higginson when she asked if her verse was “alive”âcontain only such forms, and many more contain such forms within or alongside others, commonly in the genre of the familiar letter. Yet, as we have seen, although

poetic

and

lyric

have come to seem cognate, they are not necessarilyâand certainly have not historically been thought to beâso. The instance of the letter to Austin attached to the leaf demonstrates one obvious way in which a later editor turned cadenced prose into a printed lyric. Whether such a lyric may have been imagined by Dickinson or her brother we cannot sayâbut we can say that it is not visible on the manuscript page as it is in Johnson's edition. If the lyricization of poetry has led us to read the lyric, as Michael Warner has put it, “with cultivated disregard of its circumstance of circulation, understanding it as an image of absolute privacy,” it is also worth noting that our ability to cultivate such disregard depends on the print circulation of lyrics as such.

5

Neither the leaf nor its accidental postmark is printable, and neither could be included in a volume of Dickinson's poems. The lyric reading practiced by every editor since Higginson has actively cultivated a disregard for the circumstances of Dickinson's manuscripts' circulation. By being taken out of their sociable circumstances, those manuscripts have become poems, and by becoming poems, they have been interpreted as lyrics.

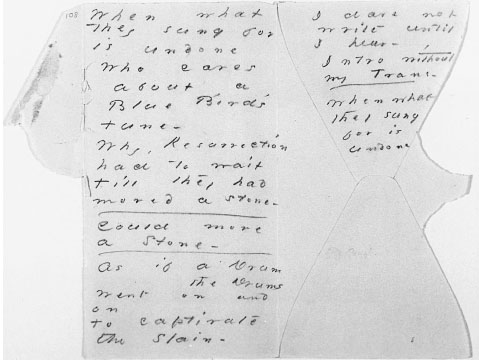

Figure 5. Courtesy of Amherst College Archives and Special Collections (ED ms. 108).

Sometimes, however, a piece of Dickinson's writing illustrates the historically fictive process of lyric reading not because it has become an imaginary poem but because it has not becomeâat least in printâa poem at all. About 1881, or thirty years after Dickinson wrote “

Here

is a little forest, whose leaf is ever green” and attached a little green (now brown and postmarked) leaf to her letter, she pencilled some linesâthis time separated, after a fashion, as verseâon the inside of a split-open envelope that was addressed (by her cousin) to herself (

fig. 5

). Here are the lines, printed as literally as possible:

When what

they sung for

is undone

Who cares

about a

Blue Bird's

tuneâ

Why, Resurrection

had to wait

till they had

moved a stoneâ

_____________________

Could move

a stoneâ

_____________________

As if a Drum

The Drum

went on and

on

to captivate

the slainâ

I dare not

write until

I hearâ

Intro without

my Transâ

_____________________

When what

They sung

for is

undone