Dickinson's Misery (35 page)

Read Dickinson's Misery Online

Authors: Virginia; Jackson

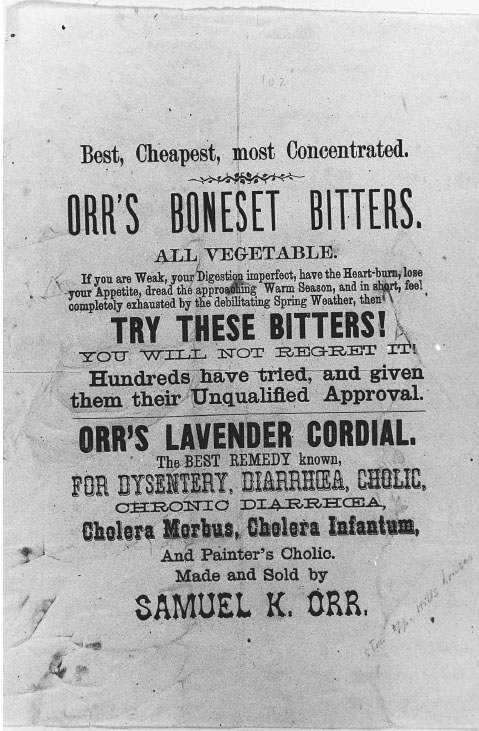

Figure 31b. Verso of manuscript in

fig. 31a

. Orr was both the druggist advertised by and the printer of the flier. Courtesy of Amherst College Archives and Special Collections.

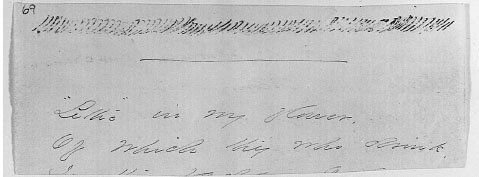

Figure 32. Courtesy of Amherst College Archives and Special Collections (ED ms. 69).

We can (and inevitably will) keep reading Emily Dickinson as one of the great examples of a subjectivity committed to the page. Yet the very insistence of that commitment urges us to reconsider our placement of the subject on the page, or within the identifying loops of reading through which she predicted her writing would be mastered.

42

In order to avoid simply repeating the interpretation foretold by that writing, perhaps we need to begin by imagining letters as something stranger than anatomies. One final detail of the “Master” letter manuscript is so strange that I hesitate to call attention to itâand yet I will do so because such hesitations are also telling. In the section of the letter that just follows the passage cited above, Dickinson writes, “if I wish with a might I cannot repressâthat mine were the Queen's placeâthe love of theâPlantagenet is my only apology.” What “the Queen's place” might be is not specified, and in any case it is not much of an apology. The referent might be part of a discourse familiar to the addressee, or it might be part of the letter's ongoing struggle over the writer's “place.” If we were to speculate on the image lyrically along these lines, we could refer it to the writer's depiction of herself as “The Queen of Cavalryâ” (F 347) and to the desire for a queenly sovereignty that she either refuses or fails to obtain in such poems as “Of Bronzeâand Blazeâ” (F 319), “I'm cededâI've stopped being Their's” (F 353), “Title divine, is mine” (F 1072) or “Like Eyes that looked on Wastesâ” (F 693). In other words, we could make the image into another poem.

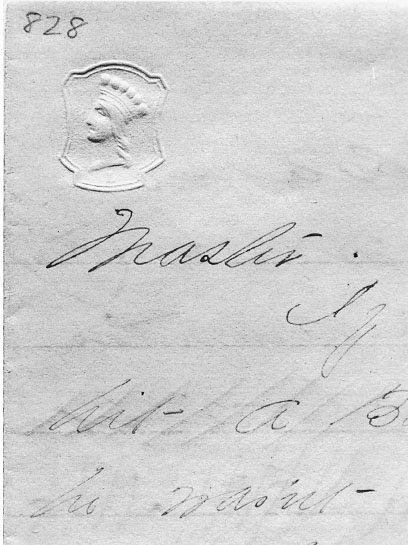

But there is another detail of this letter that, once noticed, might prove distracting to such a lyric readingâa detail we cannot help but perceive, once we see it, as at once inside and outside the lines, rather like the stamp and clippings with which this chapter began. In a tiny frame in the left-hand corner of the stationery on which the letter is written there is the embossed head of a queen poised over the capital letter

L

(

fig. 33

). The first stroke of the “

w

” in “with” (“with a might I cannot repress”) just brushes the edge of the boss's frame. The resistance that most readers will feel to any connection between the place of the queen's seal (the Queen of the

L

, we might say, the Queen of the Letter) and the place to which the writer's desire points may be taken as a measure of just how deeply repressed the historical scene of writing must be when the identity of the writer is prescribed in advance. In order to redeem a version of written identity from the transparency effected by the civilizing aspirations of the nineteenth-century legacy of a faith in anatomy, an “Orthography” imaged as neither warm and capable of earnest grasping nor as a dissected and speech-producing body should be brought into view:âSee here it isâI hold it towards you.

Figure 33. Detail of letter in

fig. 29

. Courtesy of Amherst College Archives and Special Collections.

Dickinson's Misery

“M

ISERY, HOW FAIR

”

I

HAVE NOT BEEN

arguing so far that Dickinson did not write lyrics. I have shown that she did not write the lyrics we have read: since the lyric is a creature of modern interpretation, I have suggested that we have made her writing

into

the genre we have read. In some ways, that is a story with a happy ending: as her sister Lavinia wrote in 1890, in gratitude to the editors who first made Dickinson's writing into a book, “the âpoems' would die in the box where they were found” had they not been published and received as lyrics.

1

The many historical versions of those lyrics, the many ways in which they have reflected public interest, have made them a collective enterprise, vehicles for over a century of cultural expression. Yet as I have suggested, that collective identification of and with Emily Dickinson has depended on our construction of her lyrics as private utterances. Her poems can speak for all of us because they do not speak

to

any of usâor so readers have seemed to believe. The persistence of that belief is curious, given what we have noticed about Dickinson's forms and habits of address as well as about her writing's acute concern withâeven paranoia aboutâthe ways in which what she wrote would or would not be read, who would read her, when and where. Yet that concern, too, has become part of our definition of the lyric in modernity, as the interpretation of privacy has become one way to understand public life, and as the interpretation of the lyric has come to depend on reflexivity, on formal and rhetorical self-awareness. As the lyric has been taken to represent individual expression, it has also become representative of

our

individual expressionâwhoever we are. Susan Stewart has recently made an impassioned plea for poetry as “a force against effacementânot merely for individuals but for communities through time as well.”

2

But how have we reached the point of supposing that lyric expression represents a struggle against the threat of identity's loss? And how and why has the reading of Emily Dickinson identified her as the figure who represents as well as resists that loss? In the first and second chapters, I suggested some answers to that question from the perspectives of twentieth- and twenty-first-century American lyric editing and theories of lyric reading, and in the third and fourth chapters, I suggested that those answers were derived in part from

notions about reference to others and reference to oneself. In this final chapter, I would like to suggest a very different answer from the perspective of a very different version of nineteenth-century American lyric reading, publication, address, and self-reference, a version that also found (and still seems to be finding) its personification in Dickinson.

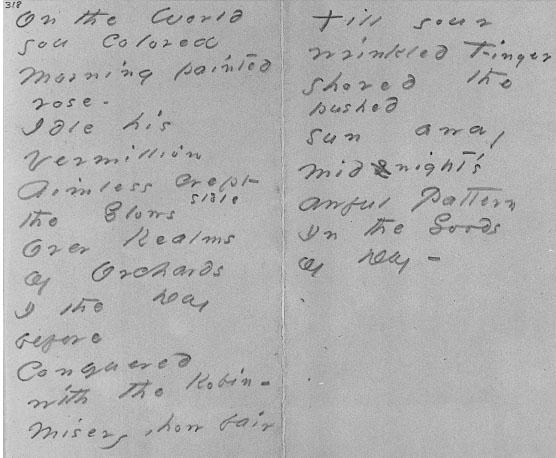

Perhaps around 1870, Dickinson penciled on a vivid blue sheet twelve lines which may or may not have been copied and sent in her lifetime, which were first published in 1945, and on which none of her later critics has commented (

fig. 34

). The lines are directly addressed, though to whom no one could say:

On the World you colored

Morning painted

roseâ

Idle his

Vermillion

Aimless crept

Stole

the Glows

Over Realms

Of Orchards

I the Day

before

Conquered

with the Robinâ

Misery, how fair

Till your

wrinkled Finger

shored the

pushed

sun away

Midnight's awful Pattern

In the Goods

of Dayâ

(F 1203)

Figure 34. Emily Dickinson, around 1870. Courtesy of Amherst College Archives and Special Collections (ED ms. 318).

These lines repeat, delicately, in variation, the outlines of the problem we have noticed in the previous chapters: in them historical determination appears indistinguishable from figurative powerâand yet the subject of these lines cannot help but tell the difference between the two. The imagery of consubstantiality that our reading of “Split the Larkâ” and the “Master” letter made explicit in the previous chapter is implicit in these lines, here as there confusing the scene of writing with a figure of direct address in the form of a sentimentally potent but comparatively powerless pathos. In the lines' terms, the “you” to whom the address is directed has prescribed (or “colored”) a “Pattern” that renders the personified Morning “Idle” and “Aimless.” The anthropomorphized description of the new day's loss of agency serves as background for the memory of the self's former anthropomorphic power “Over Realms / of Orchards,” yet the loss is depicted as representational foreground: as a “Vermillion” pentimento ineffectually concealing an unidentified experience that has intervened between one day and another. In the eighth line, the event that has made such a difference between what is seen and what is felt, between a powerful personification and what underlies it, achieves a curious identity: its name is “Misery.”

Now in one sense “Misery, how fair” may be read as a synthetic description of what the dawn looks like and how it feels, one way of aligning the contradictory claims of perception and sensibility. But what is the referent of this “Misery”? Is it the elegiac strain of “the Day / before”? Is it the ineffectual beauty of the dawn? Or is “Misery” here a figure of address, another name for “you”? If read as the latter, then this “you” has slipped from cause to effect or, like the morning, partakes of the qualities of both. Like the other apostrophes we have remarked in Dickinson's poems, the apostrophe to “Misery” performatively brings before and after into the present tense, overdetermining the ninth line's “Till” in the same way that “your / wrinkled Finger” appears excessively determinate in the poem's last lines. Like the “Wrinkled Maker” in the lines that begin “A Word / dropped Careless,” this authorial finger embodies “you” and “I,” writer and reader in the strangely amputated corporation addressed as “Misery.” This hovering “Pattern” may be sublimely “awful” but it is not, at a temporal remove, easy to readâin fact, it is its very obscurity that seems to lend it a paternal, patronizing authority. Unlike the “fingers” of “the Woman whom I prefer,” this “wrinkled Finger” destines without enabling the writer's hand; its “Midnight” spectral figure is more like that of Hamlet's pointing ghost than like the sponsoring presence revealed “where my Hands are cut” in Dickinson's early letter to Susan. On this viewâan admittedly elaborate and retrospective view, possible only in this final chapterâ“Misery” is such an apt descriptive address in these

lines because it is the best word for Dickinson's equivocal emphasis on the implicit historicity of textual intention, a pathos of transmission that has been realized beyond her wildest dreams.