Dickinson's Misery (34 page)

Read Dickinson's Misery Online

Authors: Virginia; Jackson

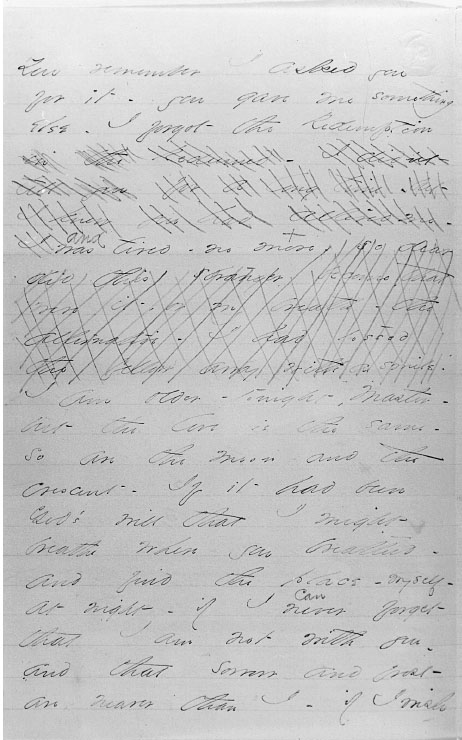

Figure 30. Emily Dickinson to “Master,” second page of

fig. 29

. Courtesy of Amherst College Archives and Special Collections (ED ms. 828).

so dear

did this stranger become, that

were it, or my breath the

alternative I had tossed

the fellow away with a smile,

[âso dear

did this stranger become, that

were it, or my breathâthe

alternativeâI had tossed

the fellow away with a smile,]

This version of redemption differs significantly from that of the lovely verse interpolation. “This stranger” is more closely related to “the big child” grown out of the built-in heart, but it is also the “something else” offered as “Redemption” for the burden of written otherness, the effect of what the addressee reclaims, “the Redeemed.” The “it” that has haunted self-inscription from the beginning is at once “dear” and a “stranger,” and the strangeness of its dearness becomes evident when “the alternative” of a choice between the two is posed: “were it, or my breathâthe / alternativeâI had tossed / the fellow away with a smile.” Does “the fellow” refer to “this stranger” or to “my breath”? The slip of the pen both parallels and unravels the optative verse alternative: the “No ⦠yet” syntax occasioned by the shift in genre is an echo of the confusion of desire briefly exposed by the letter's grammatical confusion of gender. The verse lines do not

transcend the anatomical imaginary but repeat it in another key. Even in her inadvertantly transgressive moment, the writer finds that both sexual and literary identity have already arisen from the act of writing, that she has invoked the strains of “something else” in her place.

T

HE

Q

UEEN'S

P

LACE

In the “Master” letter such textual displacements seem both tragic and inevitable (or tragic because inevitable), as in part, in the pathos of self-experience the letter represents, they must be. The mock-pathos and mock-tragedy of the lines that begin “Split the Larkâ” suggest that irony may provide a wedge between the demands of “Sceptic Thomas” and the subject of those demands, and yet the exhibition and dissection of the poetic figure are the costs of addressing the lyric reader's “doubt” as well as his “faith.” How might we begin to read Dickinson differently, against rather than in the grain of these appeals? Can Dickinson's writing be said to alter cultural assumptions about the inscription of personal and literary reference in any way other than the performance of their costs?

37

The examples I have chosen in this and other chapters have been intended as invitations to my reader to entertain the possibility that other “interpretants,” other forms of referential mediation, are indeed central to the conditions of Dickinson's writingâthough how the material history of that writing affects interpretation we may yet be too indebted to nineteenth-century Thomases to see.

In his reading of Whitman's multiple revisions of

Leaves of Grass,

Michael Moon has taken a giant step away from the Thomases by suggesting that

in an attempt to exceed or “go beyond” the modes of representing human embodiment in the discourse of his age, Whitman set himself the problem of attempting to project actual physical presence in a literary text. At the heart of this problem was the impossibility of doing so literally, of successfully disseminating the author's literal bodily presence through the medium of a book. As a consequence of this impossibility, Whitman found it necessary to undertake the project of producing metonymic substitutes for the author's literal corporeal presence in the text. Out of this difficulty arises the generative contradiction in the text of

Leaves of Grass

as I read it: that which exists between Whitman's repeated assertions that he provides loving physical presence in the text and his awareness of the frustrating but ultimately incontrovertible conditions of writing and embodiment that actually render it impossible for him to produce in his writing more than metonymic substitutes for such contact.

38

Now, Moon is writing about Whitman, and in some ways that makes all the difference between his revisionary critical project and this oneâsince, pace a tradition of criticism that pairs them as the great protomodernist, experimental American poets of the nineteenth century, there have never been two writers less like one another than Whitman and Dickinson. One thing they do have in common is the discourse of embodiment to which Moon refersâbut whereas he reads Whitman's writing as an attempt to put the (especially male, queer) body into a nineteenth-century discourse that had excised it, I read Dickinson's writing as an attempt to extricate the (especially female, queer) body from a nineteenth-century discourse that had incorporated it.

The reception of Whitman and Dickinson has conflated their very different, even opposed relation to discourses of embodiment because that reception has so essentially lyricized both writers. Both Whitman and Dickinson have become the great American poets of the self, but that is certainly not what they

were.

They both understood the lyric as one of the genres of personified identification that they sought to revise, or redeem. As Moon points out, Whitman did so by revising, over and over, the form of his writing's circulationâby revising, over and over, the same “book.” And as Michael Warner has pointed out, part of the contradiction of that insistent revision is “its own perverse publicity ⦠its use of a print publicsphere mode of address” at the same time that Whitman keeps coming on to us, keeps beckoning, “Come closer to me.”

39

Many feminist critics would claim that Dickinson also revised the form of her writing's circulation, and that rather than cultivate the contradiction of print public-sphere address, she cultivated the contradiction of scribal private-sphere address. On this view, what is perverse about Dickinson's attempt to circulate the “author's literal corporeal presence in the text” is that the manuscript forms in which she chose to do so can no longer circulate, or could just possibly still almost do so in less corporeal fashion in images on the Web or in what Susan Howe and the Dickinson Electronic Archive imagine as a facsimile edition of all the extant manuscripts.

40

But as we have seen, the cultivated perversity of Dickinson's mode of circulation consisted in disentangling rather than extenuating the cultural identification of personhood with writing. Like Whitman, she did so with what Moon calls metonyms, but unlike Whitman, Dickinson did not spin off substitutes for personal affectionate presence in print. Instead, she enclosed things in or stuck things to her writing. She distracted Thomas's gaze by giving him something else to touch.

Yet most of those things are gone. The dead cricket, various flowers or pieces of flowers, some clippings, a stamp, a few bits of fabric have survived in the archive, but the point of Dickinson's familiar circulation of

these enclosures was not their survival but their ephemeral recognition. That everyday recognition, that exchange of ephemera, was not, as Howe and other feminist readers of the manuscripts have argued, opposed to the conditions of print. As we have seen, Dickinson (often literally) enfolded print into her writing; I have been suggesting that if Emily Dickinson does not live and breathe in her writing, she

did

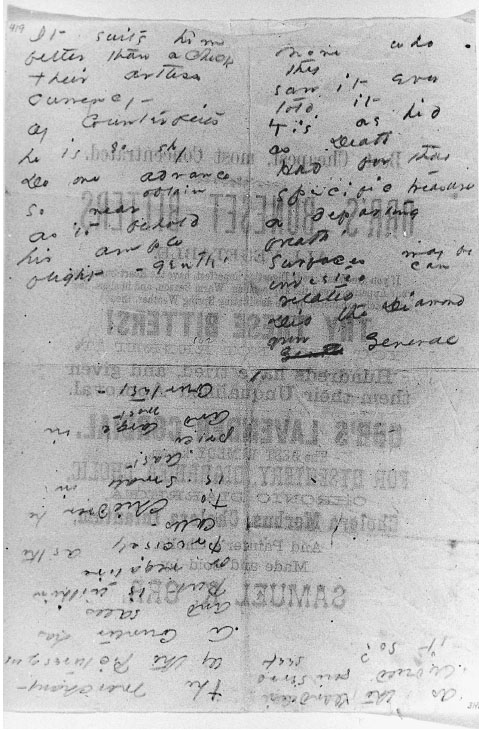

live and breathe print culture. As we have also seen, various pages and marks of that print culture not only made their way into her writing, but provided the pages on which she wrote. For Dickinson, print literally did precede handwriting, and part of the effect of its doing so is often to decorporealize and yet personalize that writing. Sometimes it is difficult to say whether the words that Dickinson then “dropped” onto those printed pages are “careless” or intentional, though the lines Dickinson wrote around 1867 on the verso of an advertising flier for “Orr's Boneset Bitters and Lavender Cordial” (

figs. 31a

,

31b

), are at the very least suggestive, at least at the distance of over a century:

The Merchant of the Picturesque

A Counter has and sales

But is within or negative

Precisely as the callsâ

To Children he is small in price

And large in courtesyâ

It suits him better than a check

Their artless currencyâ

Of Counterfeits he is so shy

Do one advance so near

As to behold his ample flightâ

(F 1134)

41

Given the elaborate ad, it is hard not to read “The Merchant of the Picturesque” as counterpart to Orr himself, or to read the print representation of Dr. Orr's “sales” as Dickinson's “Counter.” While Samuel K. Orr promises to set your bones, to anatomize you, “the Merchant of the Picturesque” is not available on demand. Yet we do not know if Dickinson's joke (if that's what it was) was addressed to anyone but herself. This is the only manuscript version of the lines, and they are barely legible at this distance.

And the situation of most of Dickinson's manuscripts is even more pathetic. So how would we have any idea what or who or where they may have pointed, other than to “Emily Dickinson”? The fragment of the lines that begin “âLethe' in my flower” (

fig. 32

), for example, is all that is left of the fascicle manuscript that Todd transcribed before she or someone else

crossed out and cut up the lines that begin “One Sister have I in the houseâ” (F 5; fascicle 2) to which the now fragmentary lines were attached. Another copy of the canceled lines was sent to Susan Dickinson in 1858, and her daughter, later Martha Dickinson Bianchi, pasted that manuscript into her copy of

The Single Hound,

her 1914 print edition of verse that Dickinson sent to her mother, a copy now kept at Harvard. The lines read:

“Lethe” in my flower,

Of which they who drink

In the fadeless Orchards

Hear the bobolink!

Merely flake or petal

As the Eye beholds

Jupiter! My father!

I perceive the rose!

(F 54)

If it is clear that the lines attached to these lines in manuscript were directly addressed to Susan (perhaps as a birthday present), there is no historical provenance for the lines Todd transcribed, no evidence of a metonymic enclosure that would attract our attention away from the lines themselvesâand yet such a principle of distracted literary perception is what the lines are about. The first four lines are a stunning condensation of Keats's Nightingale Ode (hence the citation of “Lethe” in Dickinson's first line from Keats's fourth), a variation on the play of identification with a romantic lyric figure that we noticed in the lines that begin “Split the Larkâ.” Yet the substitution of the homely American “bobolink” for the nightingale's “full-throated ease” and the transference of Keats's “vintage” to the lines themselves allow an astonishing shift in the referential layers intrinsic to lyric reading dissected in “Split the Larkâ.” The alien corn in which Keats's subject must stand in relation to the “immortal Bird” has been replaced by what “the Eye beholds” in Dickinson's. In Keats's address to the nightingale, “thy plaintive anthem fades” because it cannot be kept physically near; in Dickinson's poem, “my flower” contains “fadeless orchards” because, though “merely flake or petal,” it appears to be

there

to point to. Whether “Jupiter” names the masculine addressee (a sort of apotheosis of the “Master” or Thomas) or a patriarchal principle that collapses myth into immediate perception is anyone's guess. And it is anyone's guess whether the rose was there to perceive (though my educated guess is that it was). These lines do not finally point toward “Dickinson” but toward something lost and now unnamed and unnameableâtoward a less metaphorical context now faded from view.

Figure 31a. Emily Dickinson, around 1867. In order to begin the “poem” as reprinted here, the photograph above must be turned upside down. Courtesy of Amherst College Archives and Special Collections (ED ms. 4190).