Edie (11 page)

Authors: Jean Stein

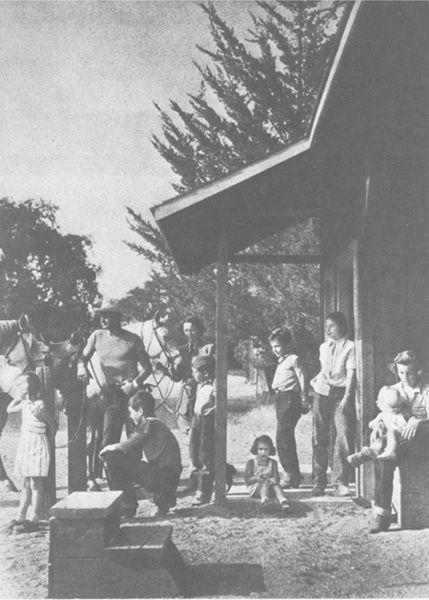

The Sedgwick family outside the tack room, Corral de Quati, 1946

(left to right):

Kate, Francis, Bobby, Alice, Jonathan, Edie, Minty, Pamela, Suky, and Saucie

HARRY SEDGWICK

I remember that dog Woof. It was so fast and powerful, it would go for whatever was in its way—pigs, deer. Once, we were riding off in the West Mesa and suddenly this horrible scream came from a clump of bushes. My uncle fuzzy jumped off his horse and went in there and pulled out the dog attached to a deer! The dog had the deer by the hindquarters, and the animal was really screaming . . . it was almost human. Fuzzy kept clubbing the dog with his quirt, or whatever they call a horsewhip out in the West, until he finally let go, and we all bounced back into the ranch. Well, this old cowboy who worked on the place heard about it, and he said he was going to get the authorities after Fuzzy and his dog. I happened to mention that to Fuzzy, foolishly, and I’ll tell you, he just hit the ceiling. He thought of it as a threat to himself! The dog, the horse, the house, the mistress–;they were all

his

. Expressions of himself. They couldn’t be tampered with. With the kids . . . well, the dogs and the horses made out a lot better. Somehow the kids were a threat to him.

SAUCIE SEDGWICK

My parents owned the land from horizon to horizon in every direction. Imagine a situation like that where nobody entered who wasn’t invited or hired! In this landscape my mother and father rooted out any influence that they could not dominate. You weren’t even told where you were going to ride that day. “Wait and see,” they’d say. “Can we go to Santa Barbara tomorrow?” “Wait and see.” As far as I know, the three little girls never went off the ranch except to go to Santa Barbara to the doctor.

Edie had so little to work with. How small the furniture of her life was! She grew up with a total lack of boundaries, a total lack of a sense of scale about herself. She was stuck in there. When I was small and growing up, I had a very distinct feeling of background and tradition—what lay back of my parents’ way of life—which was a very strong sense of being connected to my grandmother and to Uncle Ellery and my grandfather Babbo and all those older people with linen suits and silk dresses and Bostonian voices. The impression when you’re little is powerful, and it made it possible for me to reach beyond my parents to a feeling of being connected. That possibility had vanished by the time Edie came along. For her there was no sense of anything except the ranch: the world had shrunk to that.

WENDY WILDER

The Sedgwicks lived in their own world. We went over sometimes, but they were hard to know. They even had their own schoolhouse. I don’t think Edie had a good friend—horses maybe.

SAUCIE SEDGWICK

The schoolroom was very small—just a shack in the corner of the ranch where one of the cowboys had lived until my parents decided to make it into a school. My parents had kept track of a couple named Bryant they knew from New York—he had been a music student at Juilliard and she had earned money by modeling, for my father among other people. My father sent them a telegram—they were living in Oregon—proposing that they come down and run the school. In those days you could send a telegram up to ten words for a fixed amount. The Bryants sent back a telegram which read,

YES, YES, YES, YES, YES, YES, YES, YES, YES, YES!

They brought a couple of their own children with them, who were also in the school. So were the Luton children from the ranch next door. From our family were Jonathan, Kate, Edie, and Suky.

JONATHAN SEDGWICK

The Bryants arrived at the ranch in this broken-up little old car with one of those trailers behind it that fold out into a tent. He looked . . . like he’d been siphoned, you know . . . there was nothing in him . . . almost dead . . . skinny, sad, and weak. She was much stronger—tall, with a Roman nose. They taught us the Calvert System. Each kid was working at his own level. The Bryants went around the schoolroom to check up on us. I took exams for Groton and failed miserably on the writing. So I had to write essays all summer long. We weren’t allowed to go to the local public schools. Weren’t good enough for us. “We are aristocracy. We have to be educated.” We were taught in a weird way, so that when we got out into the world we didn’t fit anywhere; nobody could understand us. We learned English the way the English do, not Americans.

JOHN P. MARQUAND, JR.

They spoke in a sort of language in which the grandparents would have talked. It was always straight Grotonian all the way through and it obviously was preserved in their consciousness by the father, who just laid it onto them that they were Sedgwicks. The way you pronounced words implied a certain attitude that you took toward life and to other people in society. It would be too superficial to say that it was snobbish or arrogant, it was sort of supernatural. . . surreal.

Edie, age three

Babbo with Edie and Kate

SAUCIE SEDGWICK

We really lived in two worlds—indoors and outdoors. Outdoors, that vast physical world of the ranch, was just pure freedom and elation, especially if you were out riding alone. indoors meant inside the main house with the family. That was the world of form—very strict rules of conduct, all repressive, all belonging to that other world in the East that my parents were from.

For me, life at Corral de Quati was one long degradation. In front of anyone—guests, cowboys—my father would say I was fat, or stupid, or a liar. I remember once he introduced me to a new choreman, a guy named Lee who looked like a turkey gobbler, “This is my daughter Alice and she’s fat.” Lee said, “I got a daughter Alice and she’s fat, too,” and they both had a good laugh.

Meals were especially tense. I can remember sitting in that dining room, just waiting for the axe to fall, and being grateful when it fell on somebody else. My brother Minty told me years later that he always used to ask William, our butler, if there were going to be guests, because it would be so much easier then.

SUKY SEDGWICK

Under the bed was a refuge. I remember an earthquake. Edie came into my room. It was early in the morning because I remember my teeth chattered I was so scared. And the first thing we did was to get under my bed because that was the safest place. We clung to each other, and then somebody came in and sort of looked after us. My parents were miles away.

SAUCIE SEDGWICK

One saving grace at Corral de Quati was our grandfather Babbo, although he was so old that my mother was afraid he might die on the ranch and one of the children would find him. At Uncle Mintrn’s in the East he was the life of the party, quick-witted, well read, amusing, very much a part of the scene. But in the West, when he came out to stay at our ranch, he spent much of his time alone.

I remember Babbo stumping off every afternoon down toward the pig barns, with a gray fedora hat with a feather in it and his Harvard letter sweater tied round his neck, and a raggle-taggle of dogs behind him. He often had his supper early with the children, and we would all clamor for an installment of his tales of the Baron Munchhausen. Although he lived in a bunkhouse, he used the study in the main house: there he’d read Cicero, or Ovid, or Virgil, and laugh away as if it were some modern novel. His favorite author was Saint-Exupéry. He used

to read Caesar’s

Gallic Wars

and shout with laughter. He went out into the fields and communed with the cattle. He had pet names for those huge Hereford bulls, like Paul Potter, after the Dutch painter. The Herefords were his candidates for president of the United States. He told me once that if men were to be succeeded by another race, he hoped it would not be ants, or bees, or mosquitoes, or cockroaches, but Hereford cattle. Actually, I don’t think he could be lonely anywhere. You could set him down on the desert.

Everyone had their own separate lives on the ranch and Babbo had his. He loved to go to Santa Barbara when my mother went in to do errands or take us to the doctor. We’d leave him off at the library, and what with all the children, and everything she had to remember, sometimes my mother would forget him. One time we got all the way back to the top of the San Marcos Pass, twenty miles away, and my mother suddenly realized we’d left him behind. We went back. Babbo didn’t say a word. He was sitting outside on the bench where the buses go by and waiting for my mother to come.

Babbo also used to ride to Santa Barbara with my mother to go to the movies. He was the only one interested in them. He was much more “modern” in a sense than anyone else. He was the only person on the ranch who was interested in the news during the war. He’d sit with his hands cupped over his ears, crouched over and listening to the nurse’s radio. I remember the day Roosevelt died, Babbo said, I feel as though the world has fallen off Atlas’ shoulders.”

Babbo had a passion for mail-order houses. Once, he ordered himself a whole lot of shirts with zippers rather than buttons, and my father made him send them back because they were “too disgraceful.” It didn’t matter that he was an old man for whom zippers were much easier than buttons. He used to say that he longed for a beautiful, silent Japanese lady with delicate fingers to do up just that

one

collar button. My father felt that the zippered shirts “shamed” us. He spoke to Babbo as if he were a child: “That won’t do, Father, I’m sorry.” Babbo accepted it. He’d say, “That’s all right, Sonny.”

MINTURN SEDGWICK

Francis was the only person who seemed to disapprove when Babbo married Gabriella, whom he’d met right there on his ranch. Francis made this frightful fuss about it. He went right on refusing to see them. Saucie told me that at one point she tried to reason with him. “You must see Babbo. He’s unbelievably happy with Gabriella and your attitude causes him such sorrow.” He said, “No, I can’t help it. It’s emotional.”

SAUCIE SEDGWICK

My father went bananas. Perhaps he simply couldn’t stand the idea of Gabriella in his mother’s place. He wrote to uncle minturn: “it ain’t no good no how . . . the idea of having that horror as my stepmother makes my hair wiggle like a serpent’s.” He was even afraid they would have a baby. He wrote to a number of Babbo’s contemporaries to persuade them to intervene. And he wrote desperate letters to Babbo himself: “No one has ever come between you and me—and at the end of life in pops a total stranger. I need no psychiatrist to comprehend my distaste. “I think my father’s rage had an effect on all of us. He’d lost his father, so he thought, and he tightened his grip on the children.